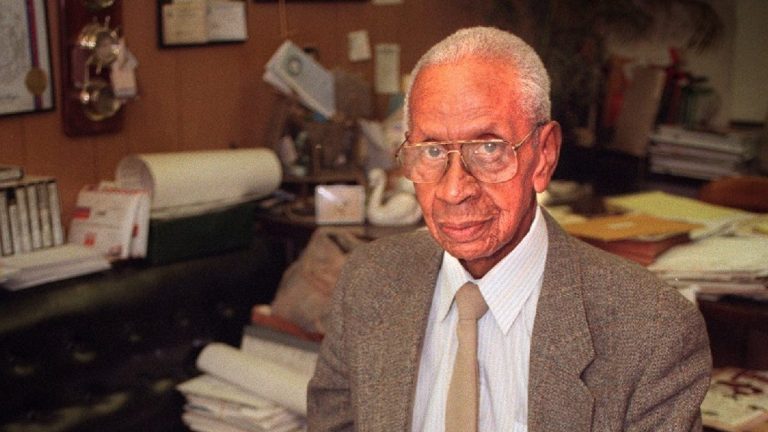

Every building Alonzo Robinson Jr. designed tells a story.

There’s Mr. Perkins Family Restaurant. The nondescript building on the corner of Atkinson Drive and North 20th Street has fed presidential candidates, celebrities like actor Danny Glover, and famous athletes including Charles Barkley and Scottie Pippen.

The Polish Association of America chose Robinson to design its new headquarters on the city’s south side in the 1960s, an era when Blacks were rarely welcomed in that part of the city. The organization found out about Robinson after it provided a mortgage for a Black church he also designed.

Robinson designed over 100 buildings over his illustrious four-decade career as Wisconsin’s first Black licensed architect.

Most notable is the Central City Plaza complex, 600 W. Walnut St. Designed in the New Formalist style, with tall arch entryways, symmetrical window placement and white concrete exterior of its buildings, it marked several firsts when it opened in 1973 — the city’s first Black shopping mall and the first developed by a Black man.

Now, efforts are underway to save a piece of Central City Plaza. The Salvation Army bought a one-story building at the corner of West Walnut and North Sixth streets, with plans to tear it down and build a homeless shelter. But the city’s Historic Preservation Commission will decide at its Feb. 3 meeting whether to grant the building permanent historic status, putting demolition plans on hold.

Chris Rute, of the Milwaukee Preservation Alliance, has pushed for the historic designation. Rute said he believes the building can be repurposed to suit the Salvation Army’s needs. The building’s cultural significance, the architect’s legacy and its quirky mid-century modern architectural style should be worth saving for future generations, he said.“Everybody understands historic buildings in the late 1800s and early 1900s,” Rute said. “One of the challenges for preservationists today is this little genre of mid-century modern, which has just turned 50. We need to consider carefully what we tear down and what we keep.”

Robinson, who died in 2000, did more than design buildings for Milwaukee’s Black community. He created the spaces and places — beauty salons, day-care centers, churches and restaurants that defined the Black community and contributed to the city’s Black business growth.

“I think this last phase of Alonzo’s career, especially in his private practice, really is his biggest legacy,” said Justin Miller, a University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee architectural historian. “He was committed to this idea of community-building — building a sustaining community.”

Miller is working on a web-based project to document Robinson’s life and works. About 120 of Robinson’s works remain, of which 80 are from his private practice. Miller believes more of Robinson’s works exist. Unfortunately, he said, architects’ names aren’t always listed on building plans, especially for a Black man during the civil rights era.

“We didn’t expect to find this many complexities in his commissions,” Miller said. “The buildings have these incredible stories behind them, but you just don’t see that by just looking at the buildings.”

The Central City Plaza was a defining project not just for Robinson but for the city’s Black community. It aimed to recapture the prominence Walnut Street had as an economic hub for the Black community up until the 1960s. Disinvestment and the construction of what’s now Interstate 43 destroyed or displaced many Black businesses during that time.

Central City Plaza was developed by civil rights leader Felmers O. Chaney. When it opened, 14 Black-owned businesses occupied the plaza. Among them were Central City Drug Store, Darby’s Food, Pago’s Liquor Store, Masterpiece Supper Club and Masterpiece Motor Lodge.

That was a remarkable feat in the 1970s since only 2% of all businesses within the state were Black, Miller said.

The feat was short-lived, though. Financial issues shuttered the plaza nearly four years later.

Robinson, a World War II veteran, came to Milwaukee to begin his architectural career in the early 1950s after getting his architecture degree from Howard University in 1951. At that time, Robinson was one of 42 Black architectural students in the entire county.

He worked for both the city and Milwaukee County governments, but many of his notable works came from his private practice, where he got commissions mostly from the city’s Black community.

“He just arrived in Milwaukee and made a name for himself with these high-profile commissions from the African American community,” Miller said.

One of his first commissions was from the then-head of the Milwaukee Urban League, William Kelly, to build a house in Wauwatosa. The home was symbolic in many ways, especially for Kelly, who’d advocated for fair and open housing.

Wauwatosa was known to have restrictive covenants prohibiting certain ethnic groups, including Blacks, from owning homes. Kelly’s home, constructed in 1957, was a subtle protest at the time.

“Building this house in this white suburb was kind of (Kelly’s) last act to show that the suburbs could be integrated,” Miller said. “This house was a really strong symbol of that.”

Robinson, Miller said, was not known to have a defining style. Instead, he designed in a variety of styles, including mid-century modern and even post-modernist styles, which were trending in the 1990s.

“He was one of those amazing architects who would give his clients what the client wanted without trying to force a style on them,” Miller said.

But Robinson’s approach was different since he designed for clientele who didn’t have large construction budgets. He used everyday materials like siding and concrete blocks to add texture to buildings. His designs were simplistic, especially for churches where congregants could construct the building themselves to save on labor costs.

“I think that takes real skill as an architect,” Miller said, adding that not too many have the ability “to get everything possible out of a client’s budget — to make that budget work within an inch of its life.”

Robinson worked for the city for 12 years, but branched out on his own, forming the architectural firm DeQuardo, Robinson & Crouch, the firm behind Central City Plaza. The firm dissolved shortly after the plaza opened, but is noted for designing industrial buildings, churches and apartments.

Struggling as an independent architect, Robinson went to work for Milwaukee County in 1975. He spent the rest of his career there until he retired in 1998. There, he did park pavilions, including the Kosciuszko Park Community Center, and the downtown Milwaukee Fire Department headquarters, for which he served as the lead architect.

The building was renamed in 2021 in Robinson’s honor to correct a slight done to him decades ago. His name had been excluded from the Fire Department’s records and at the dedication of the building.

Most of Robinson’s work for the county is hidden in plain sight. Robinson was responsible for the maintenance and upkeep of all county buildings. He designed bathroom remodels, façade restoration projects and even freezers for the morgue in the county medical examiner’s office.

“At the county, he had this really wide range of responsibilities, from brand new buildings all the way down to that kind of maintenance upkeep,” Miller said.

Robinson’s works went beyond his own architecture. He encouraged Black students to consider the profession. He aided in the fight to desegregate Milwaukee Public Schools, with his wife, Theresa, by listing his children as plaintiffs in a civil rights lawsuit brought by attorney Lloyd Barbee. And he even remodeled classrooms at a Freedom School set up for students to attend as part of a boycott of MPS.

Said his daughter, Jean Robinson, at the Fire Department ceremony in 2021: “If Dad had not been on a 50-year quest to make his profession more inclusive by shattering glass ceilings and removing all obstacles, we wouldn’t be here this morning.”