A strong showing that helped beat a charter change

In the weeks leading up to the “Black Friday” demonstration, Philadelphia Chamber of Commerce President Thacher Longstreth attacked Street for his plan, saying he doubted there would be enough support to pull off a boycott.

Longstreth called Street and his backers “irresponsible misguided idiots,” according to coverage in the Tribune.

A group of Black elected officials then threw their support behind the boycott, condemning Longstreth’s statement as racist. The group included Hardy Williams and William H. Gray III, both state representatives at the time, as well as Cecil B. Moore, then a councilmember and former president of the Philadelphia NAACP.

On the big day, a huge crowd showed up to The Gallery, according to coverage in the Inquirer and Tribune, which reported anywhere from 1,000 to 2,500 protesters. They crammed onto escalators, blocked entrances to stores and traffic in the streets outside, and shouted chants including, “Madman Rizzo’s on the loose; he must be stopped!”

Sharif Street, who was less than 10 years old during the series of Gallery protests, remembers protesters singing songs and wearing yellow and green buttons that read “Vote no on the charter change” and “Stop recycling” — referring to neighborhood recycling, or gentrification.

“That money [used for The Gallery], had it been invested in affordable housing, would have been instrumental in neighborhood stabilization,” he told WHYY News.

In Rizzo’s bid to smash through Philly’s two-term limit on consecutive mayoral terms, he cast himself as the only thing standing between his constituents in mostly white areas of the city and public housing, affirmative action, and school busing. He even told supporters at one point to “vote white.”

Sharif recalled riding through the city in the back of a pickup truck, with his father driving and his uncle, Milton, leaning out the window and shouting through a bullhorn, “Vote no on the charter change.” In parts of South Philly, where Rizzo had support, people threw rocks at them.

“Uncle Milt, they throwing rocks at us. What do we do?’” the young Street is said to have asked. The answer from his uncle: “Duck. Pick ‘em up, and throw ‘em back!’”

The Streets were not the only ones fighting Rizzo’s racist campaign ahead of the November 1978 charter change referendum. Dozens of existing organizations mobilized against it, according to coverage at the time, with at least half a dozen new coalitions formed for that sole purpose.

In the end, Rizzo lost. Voters rejected the referendum two-to-one, despite problems with voting machines that prevented thousands of Philadelphians from voting — mostly in majority-Black neighborhoods.

Priming a generation of political changemakers

Did the “Black Friday” boycott have a lasting impact on neighborhood development and business opportunities for Black Philadelphians?

Five years after the Milton Street-led action, Gallery II opened down the street from the original Gallery. The project was an “exhibition of minority participation,” per a headline in the Philadelphia Daily News, with close to a third of construction contract money going to business owners of color and nearly a quarter of the stores owned by people of color.

The Gallery II developer did receive public money — but it was a low-interest loan instead of flat-out grant, and city officials promised the money would be used for neighborhood development after it was paid back.

“This shows that minority involvement can work,” civic leader Bilal Qayyum told the Daily News. Qayyum, then head of the Philadelphia Citywide Development Corp., oversaw the committee that helped coordinate Gallery II business participation goals. “This can be a model for any economic development project in the city,” he said.

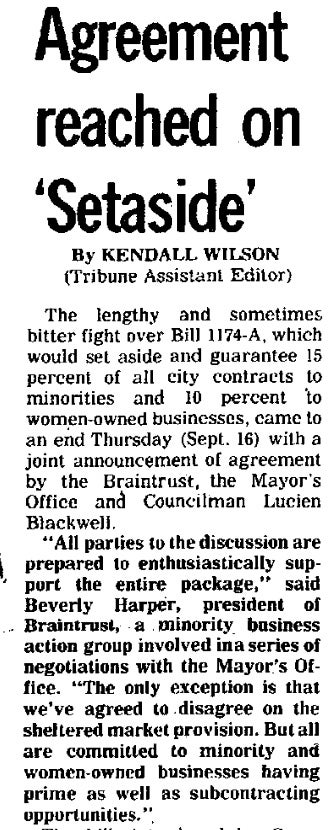

The year before Gallery II opened, City Council passed legislation that set specific goals for the percentage of city contracts that would go to businesses owned by women and people of color.

Beverly Harper, founder of community relations firm Portfolio Associates, was one of the people who spearheaded the effort. The Black Friday boycott of The Gallery was not solely responsible for this progress, she told WHYY News this week, but “it definitely played a role.”

“Any discussion or activity that raised the awareness and created dialogue around economic opportunities was important,” Harper said.

Singley, the lawyer who taught at Temple at the time of the Black Friday boycott, also sees the action as part of a broader movement: “The Gallery was a part of that tapestry of events taking place that moved the city … in a more progressive direction.”

State Sen. Sharif Street agrees. The Gallery protests helped drive greater investment in affordable housing under subsequent mayoral administrations, he said, and shaped a group of activists that went on to hold political office or work in government — including himself, and his dad, who served as Philadelphia mayor from 2000 to 2008.

“My earliest memories of protests and political activity,” Street said, “start with the Black Friday protest.”

However, the issues the demonstrators raised are still problems today, from racial disparities in government contracting to lagging opportunity for Black-owned businesses, to a lack of affordable housing.

Within a decade of Gallery II opening, the number of businesses owned by people of color had dwindled, according to reporting in the Tribune.

When it launched, Gallery II boasted 16 “non-white businesses.” By the summer of 1992, only one remained.