Exonerated

Since 1973, at least 200 Americans under sentence of death have been exonerated, meaning they have been declared legally innocent and released from death row. “For every nine people who have been executed, we’ve actually identified one innocent person who’s been exonerated and released from death row,” EJI Director Bryan Stevenson has observed. “In aviation, we would never let people fly on airplanes if, for every nine planes that took off, one would crash.” Our society does, however, willingly tolerate the risk of executing an innocent person.

A sign designating a U.S. prison’s death row unit. (Michael Brennan, Getty Images)

The vast majority of criminal convictions today result from plea bargains—agreements in which defendants plead guilty in exchange for reduced charges and/or a negotiated sentence recommendation. But jury trials remain influential because plea negotiations take place in the “shadow of the trial”: prosecutors’ decisions on whether to offer, accept, or reject pleas are shaped by the likelihood of conviction at trial. And that is, in part, dependent on what kind of jury prosecutors believe they can pick.

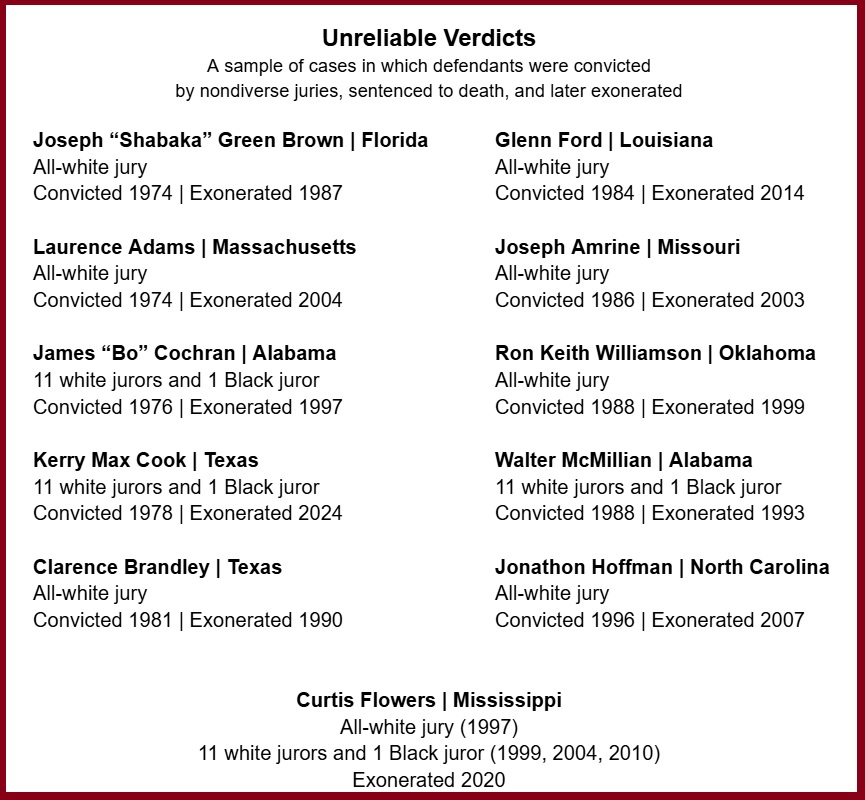

Compared to the average criminal case, death penalty cases are much more likely to go to jury trial. In some states, including Alabama, even when a defendant pleads guilty to a death penalty charge, a jury must hear the evidence and decide if it is enough to convict. Despite this greater reliance on juries, it is difficult to study jury discrimination and case outcomes—even in death penalty cases—because court transcripts and other case records often fail to document juror characteristics like race. Nevertheless, EJI has recorded more than a dozen cases of exoneration where Black people were underrepresented or wholly excluded from the trial jury.

For more information about these cases, explore Unreliable Verdicts: Racial Bias and Wrongful Convictions.

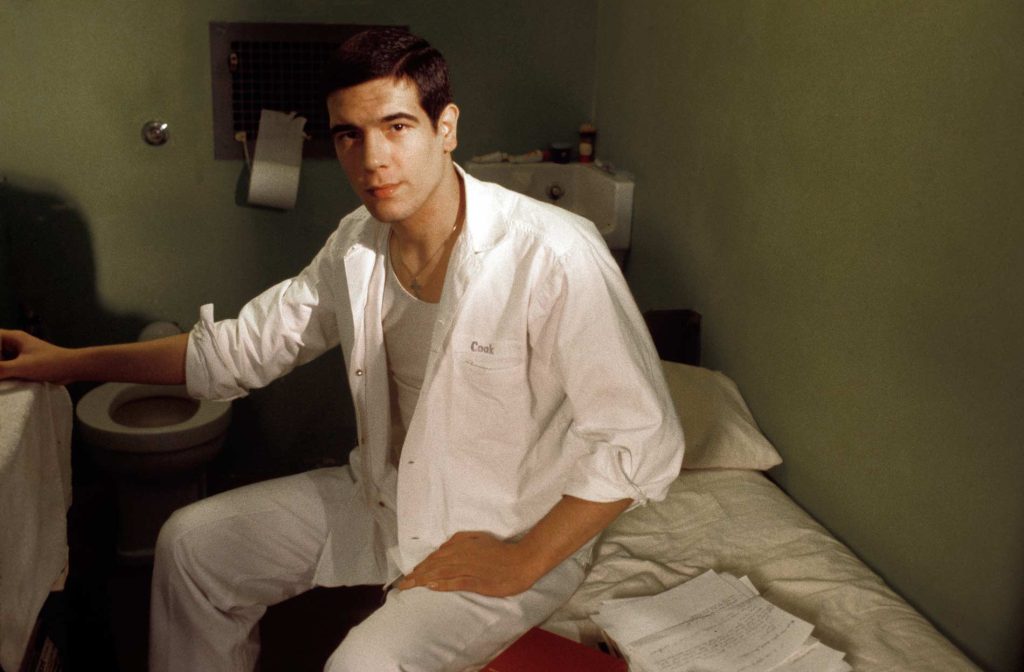

In 1978, Kerry Max Cook was convicted of killing a young white woman in Smith County, Texas. The county was then 22% Black, but Mr. Cook recalls the jury included just one Black member. “I became aware of the race and jury issue while I was on death row,” Mr. Cook told EJI in 2024. “That’s when I learned about Batson. But race plays a huge part in who gets acquitted, and who gets a fair trial. Even when you’re white, and especially when you’re poor.”

After his conviction was reversed in 1996, Mr. Cook accepted a plea deal and immediate release while still maintaining his innocence. In 1999, DNA results cleared him of the murder, and in 2024, the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals declared Mr. Cook innocent.

Kerry Max Cook on death row in Texas in 1979. (Associated Press)

In Monroe County, Alabama, in 1988, Walter McMillian was convicted and sentenced to death for the murder of a young white woman. The trial lasted only a day and a half and, though Monroe County was nearly 40% Black, the jury included 11 white jurors and one Black juror. Mr. McMillan was convicted despite testimony from multiple Black alibi witnesses placing him at a church fish fry at the time of the crime. The State’s key witness later recanted his trial testimony, but it took several years of litigation and media coverage for the State to agree to drop all charges. Mr. McMillian was exonerated and released from death row in 1993.

Walter McMillian, with arm raised, celebrated with family, friends, and attorney Bryan Stevenson after his 1993 release from Alabama’s death row.

The case of Curtis Flowers is perhaps the closest thing to a real-life case study on race, jury selection, and wrongful conviction. From his 1996 arrest to his exoneration in 2020, Mr. Flowers stood trial six times on charges of robbing and killing four people in Winona, Mississippi. He was tried in Montgomery County, where more than 40% of residents are African American.

After an all-white jury convicted Mr. Flowers in 1997, an appellate court found a Batson violation and ordered a new trial. He was convicted by a jury of 11 white jurors and one Black juror in 1999, but that conviction was also reversed. A 2004 retrial, again heard by a jury of 11 white jurors and one Black juror, resulted in another conviction—and another reversal. The fourth and fifth trials featured juries with significantly greater Black representation: five Black jurors in 2007 and three Black jurors in 2008. These juries heard the entirely circumstantial case against Mr. Flowers and could not reach a unanimous verdict; those two trials ended as mistrials.

In the final trial in 2010, a jury of 11 white jurors and one Black juror convicted Mr. Flowers and he was again sentenced to death. On appeal in 2019, a 7-2 majority of the U.S. Supreme Court reversed the conviction based on a Batson violation. “The State’s relentless, determined effort to rid the jury of Black individuals,” the Court opined, “strongly suggests that the State wanted to try Flowers before a jury with as few Black jurors as possible, and ideally before an all-white jury.” In 2020, Mississippi officials dropped all charges and Mr. Flowers was released.

After six trials over 24 years, Curtis Flowers was exonerated and released from Mississippi’s death row in 2020. (Associated Press)

As late as July 2018, Mississippi’s Clarion Ledger newspaper observed that there was “no direct evidence against [Mr.] Flowers and no reliable evidence placing him near the scene or linking him to the murder weapon.” Yet in four of six trials—each time Mr. Flowers was tried in a proceeding with one or fewer Black jurors—the jury heard the shoddy evidence, voted to convict, and condemned him to die. In contrast, each time Mr. Flowers was tried by a jury with significant Black representation—including the one time he was tried by a jury with racial proportions nearly matching Montgomery County’s overall population—the evidence proved too weak to support a unanimous verdict. In those proceedings, the juries held the prosecution to its burden, and the resulting mistrials avoided convicting and condemning a man now widely recognized as innocent.

The review of exoneration juries is largely anecdotal because incomplete records make a national review nearly impossible. New research focused on Alabama death sentences has yielded a more comprehensive view.

Cathryn Virginia