Acknowledgements

This study was funded by Women and Gender Equality Canada (WAGE). The author would like to thank the following people for their helpful comments: Évelyne Bougie, Douwere Grékou, Sylvie Guilmette, Amélie Lafrance-Cooke, Danny Leung, Horatio Morgan, Patrice Rivard and WAGE examiners.

Abstract

This article examines the socioeconomic characteristics of Black business owners in Canada and compares them with the characteristics of their White Canadian and other racialized counterparts. It also explores the characteristics of businesses based on the racial profile of owners. The analysis is based on a new linkage between the Canadian Employer–Employee Dynamics Database (2018), the Census of Population (2001, 2006 and 2016) and the 2011 National Household Survey.

For the first time,

these new data provide the opportunity for a more granular analysis of trends

in business ownership by racial profile. In this paper, the term “business owners” refers to both the

owners of private incorporated businesses and the owners of unincorporated

businesses commonly referred to as self-employed workers.

The descriptive

analysis presented in this document found that Canada had an estimated 66,880 Black business

owners in 2018, accounting for 2.1% of all business owners. The proportion of Black business owners increased among both

men and women from 2005 to 2018. A total of 70.4% of

Black business owners are men, while 29.6% are women. Black business owners are generally immigrants, and, compared with their White or other racialized counterparts, they have lower incomes on average, are less likely to be married or in a common-law relationship, and are more likely to be single.

Black owners hold 2.9%

of unincorporated businesses and 1.6% of incorporated businesses; they operate

in almost all industries. Regardless

of the type of business, those owned by Black people are on average smaller

than those owned by White people or other racialized individuals. In addition, the financial performance of Black-owned

businesses is on average weaker than that of

White-owned businesses or businesses owned by people from other racialized

groups.

1 Introduction

The ethnocultural composition of the

Canadian population has changed considerably in recent decades. According to data from the Census of Population, the

proportion of people from racialized groupsNote

almost doubled between 2001 and 2021, rising from 13.4% to 26.6%. Data from the 2021 Census highlight the differences between

racialized groups and White Canadians (White people) with respect to employment

and income. Regardless of their sex,Note

although they are more active in the labour market than their White

counterparts, racialized people were more likely to be unemployed. For example, racialized groups had a labour force

participation rate of 67.9%, compared with 62.2% for White people, and an

unemployment rate of 12.5%, compared with 9.5% for their White counterparts.Note

In 2021, the Black community (4.3%), the

third-largest racialized group after the South Asian (7.1%) and Chinese (4.7%)

populations, had an unemployment rate of 14.3%, the fifth highest of the 12

racialized groups reported in the census. In addition,

Black men had the lowest income levels compared with other men. In 2020, the annual employment income of Black women and men

averaged 84% and 69% that of their White counterparts, respectively.

To deal with these unfavourable labour market conditions, Black people and other racialized groups may turn to entrepreneurship. Business ownership can be an important driver of economic growth by promoting innovation and job creation. At the individual level, business ownership is generally associated with higher incomes than non-business owners (Grékou and Gueye, 2021). However, as with wage employment, there may be differences between racialized groups and White people in terms of business ownership. Unfortunately, unlike in the United States of America, few studies based on Canadian data have examined the characteristics of racialized business owners, maybe because of a lack of data on business ownership by racial identity. The Survey on Financing and Growth of Small and Medium Enterprises (SFGSME) and the Canadian Survey on Business Conditions (CSBC) collect information on the majority racial group that owns a business. While the results of these surveys provide the proportion of businesses that are majority-owned by racialized groups, the surveys are at the business level and do not provide information about the intersection with some individual characteristics of the owners.

Business ownership among Black people

was identified as an area with a major lack of information. In 2020, members of the Parliamentary Black Caucus said that

it is hard to change what cannot be measured,Note referring to the lack of data on

the constraints faced by Black businesses and entrepreneurs in Canada. In December

2021, the federal government announced the creation of the Black

Entrepreneurship Knowledge Hub.Note

Under the responsibility of Innovation, Science and

Economic Development Canada, the purpose of the hub is to conduct qualitative

and quantitative research on business ownership in the Black community in

Canada.

The purpose of this article is to fill the information gap

by drawing a socioeconomic portrait of business owners (self-employed or owners

of private incorporated businesses) in Canada by race. For

the first time in Canada, time series on business ownership by individuals who

identify as racialized are being made available. The

article also explores the characteristics of Black-owned businesses and

compares them with businesses owned by other racialized people or by White

people. To do this, the article is based on a unique linkage

of the Canadian Employer‒Employee Dynamics Database (CEEDD); the Census

of Population (2001, 2006 and 2016); and the National Household Survey, which

replaced the 2011 Census long-form questionnaire. The

CEEDD is used to identify business owners, their characteristics and those of

their businesses, while information on race is drawn from census data.

The data produced for this project

provide an opportunity for a more granular analysis of trends in business

ownership by racial profile. In addition, they can potentially

be used to analyze microdata, including the intersection with other

characteristics of businesses and their owners. As a

result, these new series will provide decision makers with evidence to support

them in developing public policy and adapted support programs (such as the

Black Entrepreneurship Program launched by the federal government in 2021).

This article is divided into five

sections. The following section presents the data and

methodology. The third section compares the

characteristics of Black business owners with those of other racialized groups

and White people. The fourth

section looks at the characteristics of businesses by the racial profile of their

owners, and the fifth section presents the conclusion.

2 Data

and Methodology

The data used in

this article are from the 2018 Canadian Employer–Employee Dynamics Database

(CEEDD), the Census of Population (2001, 2006 and 2016) and the 2011 National

Household Survey (NHS). The CEEDD was created and is maintained by Statistics Canada and is the result of a linkage of Statistics Canada’s Business Register with a set of personal and business tax files and other administrative data. The CEEDD identifies

business owners and their individual and family characteristics, including sex,

age, marital status and immigration status. It also

includes business characteristics, such as industry, number of employees, sales

and investments. See Green et al. (2016) for more information on the CEEDD. The Census of Population long-form questionnaire collects

information on whether an individual belongs to a racialized group. The Employment Equity Act defines visible minorities as

“persons, other than Aboriginal peoples, who are non-Caucasian in race or

non-white in colour.”

Given that the long-form questionnaire is sent to a sample

of the population, linking census and NHS data to the CEEDD helped to determine

the racial profile of 47.8% of business owners. Two

identification methods were used to assign a racial profile to business owners

who did not have to complete the long-form questionnaire. The first was based on the work of Rezai et al. (2013), which classified immigrants into a racialized group

according to their country of birth and mother tongue. Using

the sample of business owners who responded to the long-form questionnaire as a

baseline for validation showed that the results of this method were 91.9%

accurate for identifying Black individuals and 96.4% accurate for identifying

other racialized groups. Applying this method made it

possible to establish the racial profile of 62.0% of business owners (including

those already identified in the census and the NHS).

Since the country of birth and mother

tongue are available in the CEEDD only for immigrants, a mass imputation method

was used to assign a racial profile to non‑immigrant owners who did not

complete the long-form questionnaire. This method

consists of creating imputation classes from variables related to the one

needing imputation. The imputation classes created for

this project were based on the person’s age, sex, income and postal code. This method filled in the missing information for specific

individuals from available data on individuals with similar characteristics.

Gueye et al. (2022) discuss in

detail this imputation methodology and the validation exercises that were

conducted.

When the analysis is limited to owners

identified in the census or the NHS, the proportion of Black business owners is

1.4% versus 2.8% for a sample containing only imputed records or records

for which the racial profile is determined using the methodology by Rezai et al. (2013). The rate of owners identified as belonging to a

racialized group is also higher in this group. These

differences are attributable in part to a higher proportion of immigrants

within the group for which the racial profile was assigned according to the methodology used by Rezai et al. (2013) or imputed

(28.5% versus 17.3%). Black permanent resident immigrants

represented 62.7% of the Black population aged 15 years and older in 2021 (2021

Census). Of the other racialized groups, 72.3% have an

immigrant background. When temporary residents are

added, 70.7% of Black individuals and 81.5% of other racialized groups in

Canada in 2021 were immigrants.Note

For the sake of brevity, the rest of the

article does not differentiate between the observed group and the group whose racial

profile was imputed or determined using the methodology of Rezai et al. (2013). The analytical sample is limited to business owners

who were at least 15 years old in 2018. In this

article, unless otherwise specified, the term “business owner”Note refers

to both the owners of a private incorporated business and the owners of an

unincorporated business commonly referred to as self-employed workers.Note The owners of an unincorporated business, who are not required to have a business number, are excluded from the analytical sample.Note

It should be noted that there are differences between Black

people, White people and other racialized groups with respect to the type of

business generally owned. Since becoming self-employed

is less expensive than starting a private business, the financial constraint is

less drastic for Black people, who have among the lowest income levels. Self-employment therefore becomes a more accessible option for

them. As reported by Baldwin et al. (2011), entrepreneurs often start with an unincorporated

business before making the transition to incorporation if they can cover the

cost and establish the organizational form required to limit liability.

While the data and methodology used in

this article produce reliable aggregate results that are comparable with other

data sources, it is important to note that they are not without limitations.

First, the fact that racial identity is imputed for

approximately 38% to 42% of business owners is a potential source of bias in the

results. Second, the classification method of Rezai et al. (2013) is also associated with a margin of error of

4% to 8%, which is an additional source of inaccuracy.

This article examines a number of individual

and business characteristics but omits a few that may have differences between business

owners belonging to different groups. At the individual

level, having work experience, having previous business ownership, living in a rural

area or having children aged younger than 16 years are factors that may

influence the propensity for business ownership but are not included in this

study. In addition, the education level, holding of a managerial

position or mother tongue (for non-immigrants) are characteristics that may be

useful but are not yet available in the CEEDD. Therefore,

several other avenues of research can clearly be considered. This study is limited to business owners, but it may be useful

to consider differences and similarities in business ownership rates between the

Black population and other groups. Such research would help

to both assess the representativeness of the Black community in business

ownership and compare the results with those from the United States, where

research on the entrepreneurship of African Americans is more extensive.

3 Who are Black

business owners in Canada?

This section provides a comparative

analysis of selected individual and family characteristics of Black business

owners compared with those of their White counterparts and other racialized

counterparts.

3.1 More

than two-thirds of Black business owners are men

In Canada, the number of Black business

owners is estimated at 66,880 in 2018, representing 2.1% of all business owners (Table 1).

More than two-thirds (70.4%) of Black business owners are

men, and 29.6% are women. Regardless of their race, men

make up the largest proportion of business owners. The

gap between men and women is proportionally higher among the Black population.

For both men and women, the proportion of Black business

owners is lower than for Black individuals in the general population. In 2018, 2.4% of male business owners belonged to the Black

community, while Black people represented 3.0% and 3.7% of working-age men (15

years and older) according to the 2016 and 2021 censuses, respectively. Among female business owners, 1.7% were identified as Black,

but 3.1% (2016) and 3.8% (2021) of women aged 15 years and older came from the

Black community. The situation is different for other

racialized groups, among whom the proportion of male and female business owners

is higher than their proportion in the general population aged 15 years and

older.

3.2 The

proportion of Black business owners has increased over time

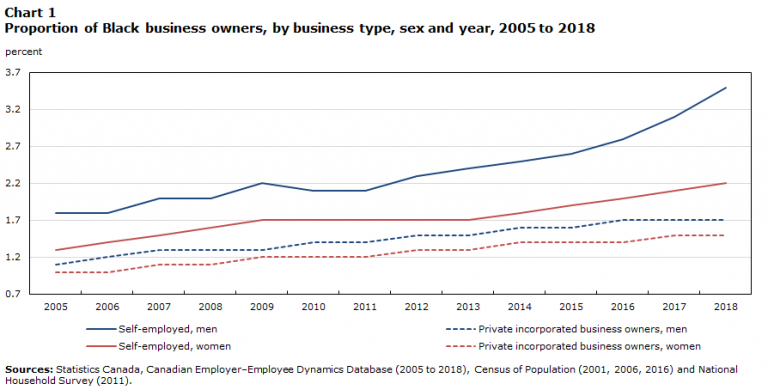

One of the benefits of linking the CEEDD

with the census is that it provides, for the first time, an opportunity to analyze trends in business ownership among racialized groups. Chart 1 shows that the proportion of owners of incorporated businesses and unincorporated businesses (self‑employed workers) who identify as members of the Black community increased between 2005 and 2018 for both men and women but at different rates. The proportion of Black men among self-employed men almost doubled during this period, from 1.8% in 2005 to 3.5% in 2018. Among women, the percentage of Black women among self-employed workers also increased (from 1.3% to 2.2%) but less quickly than for men, thus widening the gender gap in self-employment. The share of Black people among the owners of incorporated businesses also increased. Black women, who accounted for 1.0% of female owners of an incorporated business in 2005, accounted for 1.5% of them in 2018. The same was true for men, where the proportion of Black men among those who owned an incorporated business increased 0.6 percentage points, from 1.1% in 2005 to 1.7% in 2018. The fact that the proportion of Black people is increasing faster among self-employed workers than among incorporated business owners can be explained by differences in characteristics between the various legal forms of a business. In fact, incorporated businesses are generally larger, are more productive and use more capital than unincorporated businesses (Baldwin et al., 2011). Incorporated businesses therefore require a larger initial

investment.

| Men | Women | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| number | |||

| White people | 1,475,880 | 861,470 | 2,337,350 |

| Black people | 47,075 | 19,805 | 66,880 |

| Other racialized groups | 471,945 | 254,920 | 726,865 |

| Total | 1,994,900 | 1,136,190 | 3,131,090 |

| percent | |||

| White people | 74.0 | 75.8 | 74.6 |

| Black people | 2.4 | 1.7 | 2.1 |

| Other racialized groups | 23.7 | 22.4 | 23.2 |

| Total | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

Data table for Chart 1

| Self-employed, men | Self-employed, women | Private incorporated business owners, men | Private incorporated business owners, women | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| percent | ||||

| 2005 | 1.8 | 1.3 | 1.1 | 1.0 |

| 2006 | 1.8 | 1.4 | 1.2 | 1.0 |

| 2007 | 2.0 | 1.5 | 1.3 | 1.1 |

| 2008 | 2.0 | 1.6 | 1.3 | 1.1 |

| 2009 | 2.2 | 1.7 | 1.3 | 1.2 |

| 2010 | 2.1 | 1.7 | 1.4 | 1.2 |

| 2011 | 2.1 | 1.7 | 1.4 | 1.2 |

| 2012 | 2.3 | 1.7 | 1.5 | 1.3 |

| 2013 | 2.4 | 1.7 | 1.5 | 1.3 |

| 2014 | 2.5 | 1.8 | 1.6 | 1.4 |

| 2015 | 2.6 | 1.9 | 1.6 | 1.4 |

| 2016 | 2.8 | 2.0 | 1.7 | 1.4 |

| 2017 | 3.1 | 2.1 | 1.7 | 1.5 |

| 2018 | 3.5 | 2.2 | 1.7 | 1.5 |

3.3 More than half of Black

business owners are immigrants

The vast majority of Canadians who

identify as belonging to a racialized group have an immigrant background. The data from the 2021 Census of Population show that 70.9% of

racialized individuals aged 15 years and older in Canada are immigrants; the

proportion is 62.7% among the Black population. These

data are consistent with the distribution of business owners by race and

immigrant status. Immigrants represent 64.8% of Black male

business owners and 67.9% and 70.9% of women and men

in other racialized groups, respectively (Chart 2). With

the exception of White people, Black women are less likely to be immigrants; immigrants

nonetheless account for more than half of Black female business owners. Most immigrant business owners have been in Canada for more

than five years.

Black female business owners (46.5%) are

more likely to have been born in Canada than their male counterparts (35.2%).

The same is true for other racialized groups, but the gap

between men (29.0%) and women (32.1%), while statistically significant, is

smaller.

The fact that most Black or racialized business owners are immigrants is an interesting result. As reported by Picot and Ostrovsky (2021), the literature has established that the higher self-employment rate among immigrants is in part because of the constraints they face in finding suitable paid employment. Immigrants

may not be aware of the funding and support opportunities available to them;

this unawareness would be an obstacle in terms of performance and growth. A report by the Canadian Black Chamber of Commerce (2021)

indicates that, generally speaking, the Black community is not aware of the

financing programs offered by the Business Development Bank of Canada or by

Export Development Canada. This finding is also

reflected in the Canadian Survey on Business Conditions from the second

quarter of 2021.Note

Businesses owned by racialized groups (12.0%) in general or

the Black population in particular (13.6%) were twice as likely as all

businesses (5.9%) to be unaware of the support or credit programs related to

the COVID-19 pandemic. Moreover, it could be more

difficult for immigrants to access credit at financial institutions because a

good credit score takes years to build. Leung et al.

(2018) determined that immigrants are less likely to obtain

credit from formal financial institutions.

Data table for Chart 2

| White people | Black people | Other racialized groups | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men | Women | Men | Women | Men | Women | |

| percent | ||||||

| Recent immigrants | 0.8 | 0.6 | 10.2 | 6.4 | 10.6 | 7.5 |

| Established immigrants | 7.6 | 7.3 | 54.6 | 47.1 | 60.3 | 60.4 |

| Non-immigrants | 91.6 | 92.1 | 35.2 | 46.5 | 29.0 | 32.1 |

3.4 More than half of Black immigrant business owners come from

five countries

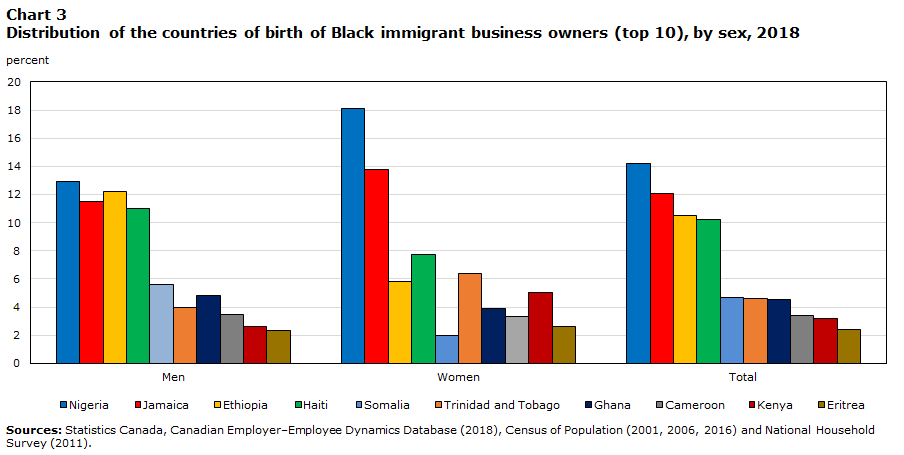

Given that more than half of Black

owners have an immigrant background, it is important to examine their countries

of origin. A Statistics Canada article (2019a) revealed

that until 1990, most Black immigrants to Canada came from the Caribbean and

Bermuda—mainly from Haiti and Jamaica. However, the

distribution has changed since the early 1990s; 65.1% of Black immigrants admitted

between 2011 and 2016 come from Africa—mainly Nigeria, Cameroon and the

Democratic Republic of the Congo. These distributions

are consistent with the distributions of Black immigrant business owners. The top five countries of origin of Black immigrant business

owners are Nigeria (14.2%), Jamaica (12.1%), Ethiopia (10.5%), Haiti (10.2%)

and Somalia (4.7%); these countries represent more than half of these owners

(Chart 3). Among both men and women, close to 70%

of immigrant business owners come from 10 countries located either in the Caribbean

and Bermuda or in Africa. Except for the top 10

countries, the Democratic Republic of the Congo (2.3%) is the only one of the

hundred other countries of birth to have a proportion of Black immigrant

business owners of more than 2.0%.

Using the Longitudinal Immigration

Database, which is a component of the CEEDD, Li (2001) showed that the country

of origin can affect the probability of a person becoming self‑employed.

He determined that immigrants from Western Europe or West

Asia were more likely to be business owners than their counterparts from Africa

or the Caribbean—the main regions of origin of the Black population in Canada.

Data table for Chart 3

| Men | Women | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| percent | |||

| Nigeria | 12.9 | 18.1 | 14.2 |

| Jamaica | 11.5 | 13.8 | 12.1 |

| Ethiopia | 12.2 | 5.8 | 10.5 |

| Haiti | 11.0 | 7.7 | 10.2 |

| Somalia | 5.6 | 2.0 | 4.7 |

| Trinidad and Tobago | 4.0 | 6.4 | 4.6 |

| Ghana | 4.8 | 3.9 | 4.5 |

| Cameroon | 3.5 | 3.3 | 3.4 |

| Kenya | 2.6 | 5.0 | 3.2 |

| Eritrea | 2.3 | 2.6 | 2.4 |

3.5 The proportion of Black Business owners is higher in Ontario

and Quebec, the provinces with the largest Black populations

The vast majority (73.9%) of Black

Canadian business owners in Canada live in Ontario or Quebec. Ontario alone (50.6%) accounts for just over half of Black

business owners, while 23.3% live in Quebec (Table 2). They are followed by Alberta (15.0%) and British Columbia

(5.4%). This finding is consistent with both the

distribution of the Black population aged 15 years and older and the results of

a survey of 700 Black female business owners in Canada conducted by the Black

Business and Professional Association (BBPA). Most

business owners from a racialized group other than Black settle in Ontario

(51.4%) and British Columbia (21.9%). Furthermore,

while the number of White business owners is highest in Ontario, its proportion

(33.7%) is nevertheless lower than the proportions of Black and other

racialized business owners.

The rate of Black business ownership is

higher in the provinces where there is a large Black community. Ontario (2.8%), Quebec (2.5%) and Alberta (2.2%) have the

highest rates of Black ownership among the provinces, and this may suggest that

Black owners offer products and services that are generally intended for their

communities. For example, a restaurant owner who

specializes in Haitian cuisine would be more likely to settle in the Montréal

metropolitan area, home of the largest proportion of Haitians in Canada. In the BBPA survey, 87.9% of respondents said that they had

started a business because they saw an opportunity to offer goods or services.

In addition, some of these female entrepreneurs reported

that their primary motivation for starting a business came from a desire to

meet the needs of their community.

| Distribution of business owners, by racial profile and province | Rate of business ownership for each racial group, by province | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White people | Black people | Other racialized groups | White people | Black people | Other racialized groups | |

| percent | ||||||

| Newfoundland and Labrador | 0.9 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 96.5 | 0.3 | 3.1 |

| Prince Edward Island | 0.5 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 93.0 | 0.3 | 6.7 |

| Nova Scotia | 2.3 | 1.2 | 0.6 | 91.8 | 1.3 | 6.9 |

| New Brunswick | 1.8 | 0.4 | 0.3 | 94.7 | 0.7 | 4.7 |

| Quebec | 23.0 | 23.3 | 9.6 | 86.4 | 2.5 | 11.1 |

| Ontario | 33.7 | 50.6 | 51.4 | 66.1 | 2.8 | 31.1 |

| Manitoba | 3.6 | 2.1 | 1.8 | 85.3 | 1.4 | 13.3 |

| Saskatchewan | 5.0 | 1.6 | 1.3 | 91.7 | 0.8 | 7.5 |

| Alberta | 15.1 | 15.0 | 12.9 | 77.4 | 2.2 | 20.4 |

| British Columbia | 13.9 | 5.4 | 21.9 | 66.9 | 0.7 | 32.4 |

| Territories | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 86.7 | 2.7 | 10.6 |

3.6 Black business owners are on

average six years younger than their White counterparts

For both men and women, Black business

owners and those from other racialized groups are on average 47 years of age, 6

years younger than their White counterparts (53 years) (Chart 4). The Black population is younger than the general population in

Canada. Among Black people, 80.6% of men and 78.7% of

women are aged younger than 50 years (Statistics Canada, 2019b), while the

proportion in the total population is 63.4% and 61.3% for

men and women, respectively. Despite the young Black

population, the vast majority of business owners in this community are aged

older than 40 years.Note This finding suggests that there is a need to gain experience

and accumulate capital, two criteria that are generally acquired over time

(Shinnar and Young, 2008).

Data table for Chart 4

| White people | Black people | Other racialized groups | |

|---|---|---|---|

| years | |||

| Men | 53 | 47 | 47 |

| Women | 53 | 47 | 47 |

3.7 Black business owners are less likely to be married or in a

common-law relationship than their White counterparts or other racialized

counterparts

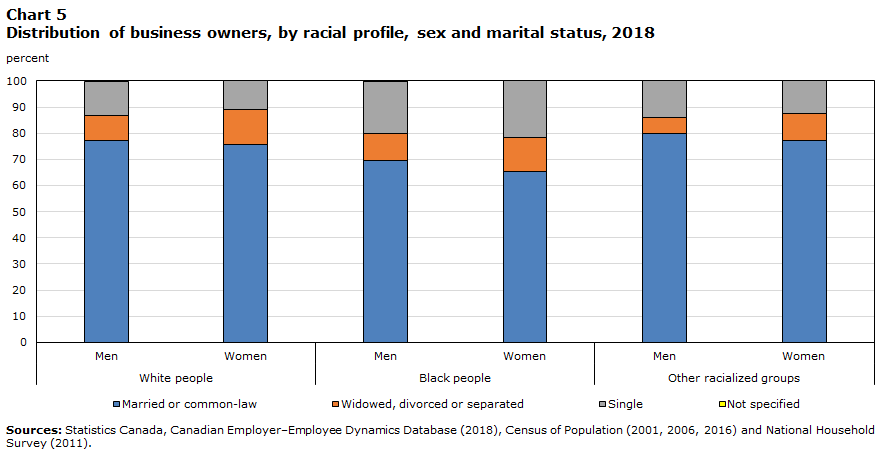

Several studies have found that family

composition is a factor that can influence the decision about whether to start

a business (Lin et al., 2000; Ozcan, 2011; Eliasson and Westlund, 2013). Grékou and Gueye (2021) showed that the likelihood of owning a business is higher among people who are married or in a common-law relationship and among widowed, divorced or separated individuals than among single people. Budig

(2006) argued that the positive effect marriage has on the probability of

starting a business can be explained by the increase in family wealth. Among both men and women, Black people (69.6% for men and

65.3% for women) were not only less likely to be in a relationship, but also

more likely to be single (Chart 5). In addition,

people from other racialized groups (77.4% for women and 80.0% for men) are more likely

to be married or in a relationship than White and Black people, regardless of

sex. These differences could help explain possible

disparities between groups in terms of access to or retention of business

ownership.

3.8 The incomes of Black business owners are lower on average

than the incomes of White people or other racialized groups

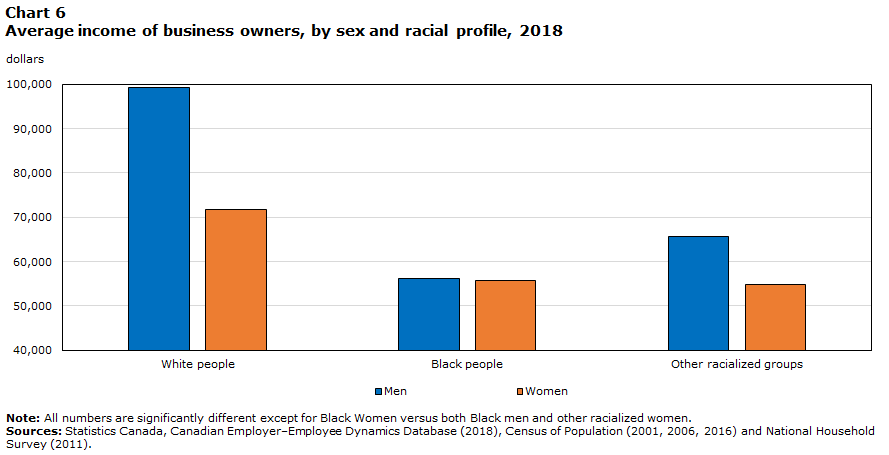

Despite the continued diversification of the Canadian

population, inequalities in income and access to employment can still be

observed between racialized groups and White people. Data from the 2021 Census

show that people who identify as belonging to a racialized group are more

likely than White people to be unemployed, even though they are more active in the

labour market.

In addition, the total income before tax of racialized men

is on average $11,140 less than that of their White counterparts. The gap is

smaller for women, but still in favour of White people (+$5,560 than the income of

women belonging to racialized groups). These income differences between White

people and racialized groups within the general population are also noticeable

among business owners. Among male business owners, the incomes of Black

individuals ($56,100) are the lowest on average (Chart 6). They earned $9,500

less than their counterparts from other racialized groups and $43,300 less than

White men. There is no statistically significant difference between Black women

($55,700) and their racialized counterparts ($54,800). However, on average,

they earned more than $16,000 less than White women.

Financial considerations are an important factor for the

creation or survival of a business (Evans and Leighton, 1989; Leung et al.,

2018; Grékou and Gueye, 2021). In the BBPA study, 81.4% of Black female

business owners reported having used their own funds to start their business.

Some added that access to financing and the costs of loans are major obstacles

to owning a business. This finding is consistent with the hierarchical theory

of Myers and Majluf (1984) that personal funds are the primary source of

financing, followed by loans. Considering the importance of financial resources

in business ownership, the low level of income of Black individuals compared

with White individuals and other racialized groups could be an obstacle for

both owners (staying in business and growing) and employees (accessing business ownership).

Data table for Chart 5

| White people | Black people | Other racialized groups | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men | Women | Men | Women | Men | Women | |

| percent | ||||||

| Married or common-law | 77.3 | 75.8 | 69.6 | 65.3 | 80.0 | 77.4 |

| Widowed, divorced or separated | 9.6 | 13.4 | 10.2 | 13.1 | 6.0 | 10.0 |

| Single | 13.0 | 10.8 | 20.1 | 21.6 | 14.0 | 12.6 |

| Not specified | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

Data table for Chart 6

| White people | Black people | Other racialized groups | |

|---|---|---|---|

| dollars | |||

| Men | 99,400 | 56,100 | 65,600 |

| Women | 71,800 | 55,700 | 54,800 |

3.9 Black people are more likely to be new business owners than White people and other racialized groups

In this section, recent immigrants were

removed from the sample as it is possible that they were not in Canada between

2013 and 2017. After having determined the racial

profile of business owners in 2018,Note the longitudinal

nature of the CEEDD helped to determine whether they were also business owners

in previous years, given that their 2018 racial profile is assumed to be the

same across time.

Among Black male business owners in 2018, 48.1% were in business throughout the period from 2013 to 2017, compared with 57.9% for men belonging to other racialized groups and 72.5% for White people (Table 3). This is also true among women who were business owners in 2018; the proportion who were also business owners between 2013 and 2017 is lower among Black women (46.3%) than among their White (66.2%) or other racialized (53.5%) counterparts.

Conversely, among Black men, 14.0% of business owners were entrants, or individuals who were not business owners between 2013 and 2017 but became owners in 2018, compared with 9.4% among men from other racialized groups and 5.5% among White men. The same is true for Black women (13.9%) compared with White women (6.9%) and women from other racialized groups (9.8%).

These differences in the number of years

of activity as a business owner between 2013 and 2017 could be related to the

type of ownership.Note

Grékou and Liu (2018) determined that self-employed people

had lower survival rates than owners of private incorporated businesses. A study focusing on motivations to enter or exit business

ownership would help to determine whether survival is less likely among Black

people because of their employment situation. For

example, did the Black people who became self-employed do so to get out of

unemployment or did they end their business activities as soon as they found

payroll employment?

| Years as an owner | White people | Black people | Other racialized groups | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men | Women | Men | Women | Men | Women | |

| percent | ||||||

| 0 | 5.5 | 6.9 | 14.0 | 13.9 | 9.4 | 9.8 |

| 1 | 5.5 | 6.9 | 12.1 | 11.8 | 8.8 | 10.0 |

| 2 | 5.6 | 7.0 | 9.5 | 10.5 | 8.2 | 9.6 |

| 3 | 5.2 | 6.3 | 8.0 | 8.8 | 7.6 | 8.6 |

| 4 | 5.9 | 6.7 | 8.3 | 8.6 | 8.0 | 8.4 |

| 5 | 72.5 | 66.2 | 48.1 | 46.3 | 57.9 | 53.5 |

4 Which types of

businesses do Black individuals own?

In this second part of the article, the

unit of analysis is the business, to determine whether the characteristics of

businesses vary according to the majority racial profile in business ownership.

Since private incorporated businesses generally differ from

unincorporated businesses (Baldwin and Rispoli, 2010; Baldwin et al., 2011),

they will be examined separately. A methodology based

on the work of Grékou et al. (2018) to identify

businesses owned by women and men was used to assign a racial profile to a

business. A business is said to belong to a racial

group (White people, Black people and other racialized groups) if more than

half of its shares are held by individuals who identify with that group. In the event of equal shares, the business is assigned to

Black people and to other racialized groups (in this order). For example, if Black people and those from other racialized

groups each hold 50% of the shares, the business is said to be owned by Black

people. However, when White people and other racialized

groups each hold 50%, the business is said to be owned by another racialized

group.

4.1 Black

people own a higher proportion of unincorporated businesses than private

incorporated businesses

Table 4 shows that 2.9% of unincorporated businesses

and 1.6% of incorporated businesses are Black-owned. This finding indicates that Black people are more likely to be

unincorporated self-employed workers than incorporated business owners. Individuals belonging to other racialized groups own 21.8% of

unincorporated businesses and 24.2% of incorporated businesses.

An alternative definition to majority

ownership is participation, meaning that a business

would be considered Black if at least one of the owners identified as Black.

According to this definition, 3.1% of unincorporated

businesses and 2.2% of incorporated businesses are owned by Black people. The fact that the two definitions produce almost similar

results for Black people suggests that Black business owners tend to be sole

proprietors or associate with other Black people. The definition

based on majority ownership will be used in the remainder of the article.

| Race | Unincorporated businesses | Private incorporated businesses | All private businesses |

|---|---|---|---|

| number | |||

| White people | 854,600 | 1,013,700 | 1,868,300 |

| Black people | 32,600 | 22,200 | 54,800 |

| Other racialized groups | 247,100 | 329,800 | 576,800 |

| Total | 1,134,300 | 1,365,600 | 2,499,900 |

| percent | |||

| White people | 75.3 | 74.2 | 74.7 |

| Black people | 2.9 | 1.6 | 2.2 |

| Other racialized groups | 21.8 | 24.2 | 23.1 |

| Total | 100 | 100 | 100 |

4.2 Transportation and warehousing, and professional, scientific

and technical services are the main fields of activity of Black-owned businesses

The distribution by industry—defined by

the two-digit North American Industry Classification System code—is almost the

same for unincorporated businesses, whether they are owned by Black people,

White people or other racialized groups. The

transportation and warehousing industry (34.3%) has the largest number of

Black-owned unincorporated businesses (Table 5). It

is followed by real estate and rental and leasing (13.4%) and professional,

scientific and technical services (10.4%), which represent the first- and third-largest

industries of unincorporated businesses owned by White people or other

racialized groups. The transportation and warehousing industry

(19.8%) has the second-largest number of unincorporated businesses owned by

other racialized groups. The agriculture, forestry,

fishing and hunting industry, the second largest for unincorporated businesses

owned by White people (17.7%), accounts for 1.1% and 1.5%, respectively, of

businesses owned by Black people and other racialized groups. The construction industry and the administrative and support,

waste management and remediation services industry round out the top five industries

for private unincorporated businesses owned by Black people or other racialized

groups.

Among private incorporated businesses, professional, scientific and technical services account for the largest number of businesses, regardless of the racial group to which the owners belong (17.7%,

21.3% and 19.8% for businesses owned by White people, Black people and other

racialized groups, respectively). Transportation and

warehousing (14.2%), health care and social assistance (12.3%), construction

(9.8%), and retail trade (7.8%) are the other four industries that include the

largest number of private incorporated businesses owned by Black people. These industries are also the top five for businesses owned by

other racialized groups, but in a different order than that of Black people.

The distribution by industry of

Black-owned private incorporated businesses is comparable to that of businesses

owned by other racialized groups but somewhat different from that of White-owned

businesses. For example, Black‑owned private

incorporated businesses are about twice as likely to be in the transportation

and warehousing or health care and social assistance industries as White-owned

businesses. The top five industries for Black-owned

private incorporated businesses account for 65.4% of all private incorporated

businesses owned by this community, while these same industries represent 52.5%

of White-owned private incorporated businesses. Conversely,

White-owned businesses have a stronger presence in agriculture, forestry,

fishing and hunting; mining, quarrying, and oil and gas extraction; and

utilities.

| Unincorporated businesses owned by | Private incorporated businesses owned by | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White people | Black people | Other racialized groups | White people | Black people | Other racialized groups | |

| percent | ||||||

| Agriculture, forestry, fishing and hunting | 17.7 | 1.1 | 1.5 | 6.0 | 0.8 | 0.6 |

| Mining, quarrying, and oil and gas extraction, and utilities | 0.8 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 1.2 | 0.3 | 0.2 |

| Construction | 11.0 | 8.3 | 8.2 | 15.4 | 9.8 | 9.8 |

| Manufacturing | 2.0 | 1.4 | 1.3 | 4.1 | 2.5 | 2.8 |

| Wholesale trade | 1.1 | 1.1 | 1.1 | 4.1 | 3.1 | 4.4 |

| Retail trade | 4.8 | 4.8 | 5.2 | 7.2 | 7.8 | 10.0 |

| Transportation and warehousing | 4.4 | 34.3 | 19.8 | 5.0 | 14.2 | 14.1 |

| Information and cultural industries | 1.5 | 1.4 | 1.3 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.1 |

| Finance and insurance | 1.0 | 1.3 | 1.6 | 7.4 | 3.2 | 3.5 |

| Real estate and rental and leasing | 20.2 | 13.4 | 27.8 | 7.8 | 4.7 | 5.8 |

| Professional, scientific and technical services | 14.2 | 10.4 | 11.9 | 17.7 | 21.3 | 19.8 |

| Management of companies and enterprises | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.7 | 0.3 | 0.3 |

| Administrative and support, waste management and remediation services | 5.0 | 7.7 | 6.5 | 4.3 | 6.5 | 3.9 |

| Educational services | 1.1 | 1.1 | 1.1 | 1.0 | 1.3 | 1.3 |

| Health care and social assistance | 3.9 | 3.4 | 3.4 | 7.2 | 12.3 | 8.6 |

| Arts, entertainment and recreation | 3.0 | 2.8 | 1.7 | 1.4 | 1.3 | 0.7 |

| Accommodation and food services | 1.5 | 1.3 | 1.6 | 3.2 | 3.7 | 8.0 |

| Other services (excluding public administration) | 6.9 | 6.1 | 5.8 | 4.9 | 5.5 | 5.2 |

4.3 Businesses owned by Black people are on average smaller than

those owned by White people or other racialized groups

Unincorporated businesses owned by Black

people are generally smaller than those owned by other groups in terms of the

size of the business measured by the number of employees. In fact, 95.6% of unincorporated businesses owned by Black

people have fewer than one employee, compared with 92.7% and 89.6% for those

owned by other racialized groups and White people, respectively (Chart 7).

This finding is not surprising, because unincorporated

self-employed workers often carry out their activities individually. However, it should be noted that unincorporated businesses

owned by White people (10.3%) are twice as likely to have at least one

employee as businesses owned by Black people (4.4%). A

total of 7.3% of unincorporated businesses owned by other racialized groups have

at least one employee.

The distribution by employment size is less concentrated for private incorporated businesses, although more than half of them had fewer than one employee regardless of the racial profile of the owners. Black-owned private incorporated businesses are generally smaller than those owned by their White or other racialized counterparts. A total of 91.2% of Black-owned private incorporated businesses have fewer than five employees compared with 87.9% for other racialized groups and 83.1% for White people. Conversely, Black-owned businesses (8.8%) are almost half as likely as White-owned businesses (17.0%) to have five or more employees. Compared with businesses owned by other racialized groups, Black-owned businesses are 1.4 times less likely to have five or more employees.

These results reflect the importance of

small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) to the Canadian economy and are

consistent with those of ISEDNote

(2019), which found that in 2017, 89.6% of employment came from small (fewer

than 100 employees) and medium‑sized (100 to 499 employees) enterprises. Moreover, when only SMEs are considered, about 98% of

businesses are small, regardless of whether they belong to racialized groups

(ISED, 2020).

Data table for Chart 7

| White people | Black people | Other racialized groups | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UB | IB | UB | IB | UB | IB | |

| percent | ||||||

| less than 1 employee | 89.6 | 51.0 | 95.6 | 60.9 | 92.7 | 49.7 |

| 1 to 4 employees | 7.8 | 32.1 | 3.4 | 30.3 | 5.8 | 38.2 |

| 5 to 19 employees | 2.3 | 12.4 | 0.9 | 6.9 | 1.4 | 9.9 |

| 20 to 99 employees | 0.2 | 4.0 | 0.1 | 1.7 | 0.1 | 2.1 |

| 100 or more employees | 0.0 | 0.5 | 0.0 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.2 |

4.4 Financial

performance is lower for Black-owned businesses

This section is limited to private

incorporated businesses and provides some financial results for businesses by

the racial profile of owners. The literature has shown

that the financial performance of businesses varies based on certain owner characteristics

(Fairlie and Robb, 2009, for gender differences; Bemrose and Lafrance-Cooke,

2022, comparing persons with disabilities with those without disabilities).

As shown in Table 6, Black-owned

businesses perform less well financially on average than those owned by White

people or other racialized groups. In fact, Black-owned

businesses have the lowest levels of gross income and profit, followed by those

owned by other racialized groups. In addition, the

amounts reported by businesses owned by White people are on average nearly

three times higher than those reported by businesses owned by Black people and

twice as high as those of businesses owned by other racialized groups. However, spending and debt levels are lower for Black-owned

businesses.

Investment, measured by physical capital

held, is also lower on average for businesses owned by Black people ($190,800)

than for businesses owned by White people ($617,600) or other racialized groups

($274,400). The gap between Black-owned and White-owned

businesses is not attributable to the extreme values of some large White-owned

businesses that would affect the average. Median values

also reveal differences in favour of White-owned businesses over

Black-owned businesses.

These different financial performances

do not necessarily indicate that Black-owned businesses are less profitable.

The rate of return on assets (net income divided by total

assets) and profit margin (difference between income and costs expressed as a

percentage of income) are measures frequently used to estimate a business’s

profitability. Black-owned businesses (5.2%) have on

average a lower rate of return on assets than those owned by White people

(10.6%) or other racialized groups (9.3%). This means

that Black-owned businesses have a weaker capacity to use their assets to

generate gains. In addition, the profit margin is also

to the advantage of White-owned businesses (14.9% compared with 8.5% for

Black-owned businesses), meaning that White-owned businesses have a better

ability to profit from their activities and have more room to maneuver to cope

with rising costs or competition. Although these ratios

are good indicators of business profitability, they may be affected by factors

other than the racial profile of owners, such as the business sector.

Fairlie and Robb (2007) explain that

White-owned businesses in the United States are more successful than

Black-owned businesses because the latter are less likely to come from a

family of business owners and to have worked in the family business. Such a hypothesis could explain in part the differences in

performance between businesses owned by Black and White people in Canada. The vast majority of Black business owners in Canada are

immigrants and thus constitute the first generation of their families in the

country.

Unsurprisingly, the value of exports

differs according to the racial profile of the owners of the exporting

business. On average, exports of Black-owned businesses

($884,100) are equivalent to about 53% of those of businesses of other

racialized groups ($1,667,000) and 25% of exports of White-owned businesses

($3,540,000). However, the propensity to export is

comparable between businesses owned by White people, Black people or other

racialized groups. Immigration has a positive effect on

trade between Canada and the countries of origin of immigrants (Wagner, Head

and Ries, 2002). In addition, immigrant entrepreneurs

export mainly to their country of origin (Fung, Grekou and Liu, 2019; Morgan,

Sui and Malhotra, 2021), probably because of their understanding of the market needs

and their knowledge of local languages. The data used

in this document show that 31.6% of immigrant-owned exporting businesses have

exported to the country of origin of their immigrant owners. Black entrepreneurs (57.1%) are more likely to export goods

or services from Canada to their country of origin, followed by those from

other racialized groups (36.0%). Among the businesses

owned by White immigrants, 19.8% exported to the country of origin of the

owners.

| Businesses owned by | Significance test | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White people | Black people | Other racialized groups | White people and Black people | Black people and other racialized groups | White people and other racialized groups | |

| dollars | importance (p-value) | |||||

| Assets | 1,712,200 | 747,000 | 699,700 | 0.008 | 0.892 | 0.000 |

| Tangibles assets | 617,600 | 190,800 | 274,400 | 0.000 | 0.039 | 0.000 |

| Liabilities | 894,000 | 313,700 | 442,300 | 0.000 | 0.157 | 0.000 |

| Revenue | 1,211,100 | 460,300 | 645,300 | 0.000 | 0.025 | 0.000 |

| Expenses | 1,030,200 | 421,300 | 580,100 | 0.000 | 0.066 | 0.000 |

| Profit | 180,900 | 39,000 | 65,200 | 0.000 | 0.142 | 0.000 |

| Value of exports | 3,540,000 | 884,100 | 1,667,000 | 0.000 | 0.001 | 0.001 |

5 Conclusion

For the first time in Canada,

administrative data have been used to determine the intersection between the

racial profile (White people, Black people or other racialized groups) of

business owners—meaning unincorporated self-employed workers and private

incorporated business owners—and selected sociodemographic (e.g., sex, immigrant

status, age or marital status) and economic (income, ownership type and

longevity as a business owner) characteristics. This

article also explored the differences and similarities in the characteristics

of businesses owned by White people, Black people and other racialized groups.

This work, which aligns with the federal government’s

effort to fill a data gap on Black business owners to better inform public

policy, was made possible thanks to a linkage between the 2018 Canadian

Employer–Employee Dynamics Database; the 2001, 2006 and 2016 Census of

Population; and the 2011 National Household Survey. These

new data will enable a more disaggregated analysis of trends in

business ownership by racial profile combined with other individual and

business characteristics.

There were an estimated 66,880 Black business owners in 2018, the vast majority of whom were men (70.4% versus 29.6% for women). Black people account for 2.1% of all business owners, and more than half of them have an immigrant background.

On average, Black business owners and

those of other racialized groups are about six years younger than their White

counterparts. There are income gaps in favour of White

people and other racialized groups compared with Black people. In addition, Black people are not only less likely than White

people and other racialized groups to be married or in a relationship, but also

more likely to be single. Black business owners

generally reside in Ontario (50.6%) or Quebec (23.3%). Black

business ownership rates are also higher in provinces with higher Black

populations (Ontario [2.8%], Quebec [2.5%] and Alberta [2.2%]).

Black-owned businesses—defined as

businesses in which individuals who identify as Black hold more than half of

the shares—account for 2.9% of unincorporated businesses and 1.6% of

incorporated businesses. The distribution by industry

of unincorporated Black-owned businesses is comparable to that of other groups.

More than 97% of these businesses have fewer than five

employees, regardless of the racial profile of their owners.

The difference between Black-owned

businesses and those owned by White people or other racialized groups is more

apparent for private incorporated businesses. Although

professional, scientific and technical services are the industry with the

largest number of businesses for all types of owners, the distribution by

industry differs somewhat between Black- and White-owned businesses. Moreover, Black-owned businesses are generally smaller (number

of employees) than those owned by White people or other racialized groups. Income, sales, assets, investments and export value are on

average at least twice as low for Black-owned businesses compared with those

owned by White people.

Although the findings are comparable to

results from previous research, it is clear that the imputation of the racial

profile of some business owners could affect the accuracy of the data. To reduce the amount of imputed data, it is possible, for

example, to include more censuses or surveys in which racial profile

information is collected. In future research, it would

be interesting to examine the determinants of business ownership among Black

people and see how they differ from those of other groups. Such an analysis would provide a better understanding of the

factors that influence the decision of Black people to become business owners.

The CEEDD would also enable tracking the trajectory of

business owners. In other words, it would be possible

to track for a period of time a cohort whose members became business owners in

a given year and determine their performance with respect to survival and growth,

among other factors. It may also be interesting to see

how Canadian-born Black people compare with Black immigrants in terms of the

labor market in general and business ownership in particular.

Bibliography

Baldwin, J., and L. Rispoli. 2010. Productivity Trends of Unincorporated Enterprises in the

Canadian Economy, 1987 to 2005. The Canadian Productivity

Review, No. 28, Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 15-206-X. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/fr/pub/15-206-x/15-206-x2010028-eng.pdf?st=EJBaetSX

Baldwin, J., D. Leung and L. Rispoli.

2011. Labour Productivity of Unincorporated Sole

Proprietorships and Partnerships: Impact on the Canada-United States

Productivity Gap. Economic Analysis Research Paper Series, no. 71,

Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 11F0027M. https://www150,statcan.gc.ca/n1/fr/pub/11f0027m/11f0027m2011071-eng.pdf?st=bC4GbZzB

Bemrose R. and A. Lafrance-Cooke. 2022.

Business ownership among persons with disabilities in

Canada. Analytical Studies Branch: Economic and Social

Reports. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 36-28-0001. https://www150,statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/36-28-0001/2021012/article/00004-eng.htm

Black Business and Professional

Association, Casa Foundation, de Sedulous Women Leaders, and Women

Entrepreneurship Knowledge Hub. (2021). Rise up: A

study of 700 Black women entrepreneurs. https://wekh.ca/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/BBPA-Rise-Up.pdf

Canadian Black Chamber of Commerce. (2021). Building Black Businesses in Canada. Personas,

Perceptions & Experiences. https://www.blackbusinessbc.ca/resources/Building-Black-Businesses-in-Canada-_Feb-27-2021.pdf

Eliasson, K. and H. Westlund. 2013. Attributes influencing self-employment propensity in urban and

rural Sweden. The Annals of Regional Science, 50,

479–514.

Evans, D. S. and L. S. Leighton. 1989. Some empirical aspects

of entrepreneurship, American Economic Review, 79,519–535.

Fairlie, R. W., and Robb, A. M. (2007).

Why Are Black‐Owned

Businesses Less Successful than White‐Owned

Businesses? The Role of Families, Inheritances, and

Business Human Capital. Journal of Labor Economics,

25(2), 289–323. https://doi.org/10,1086/510763

Fairlie, R., and A. Robb. 2009. “Gender Differences in Business Performance: Evidence from the

Characteristics of Business Owners Survey,” Small Business Economics, vol. 33, no. 4, 375–395.

Fung, L., Grekou, D., Liu, H. 2019.

The Impact of Immigrant Business Ownership on International

Trade. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 11F0019M no. 426. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/11f0019m/11f0019m2019014-eng.htm

Green, D., H. Liu, Y. Ostrovsky and G.

Picot. 2016. Immigration, Business Ownership and

Employment in Canada Analytical Studies Branch Research Paper Series, no. 375

Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 11F0019M. https://www150,statcan.gc.ca/n1/fr/pub/11f0019m/11f0019m2016375-eng.pdf?st=kjiyJvGy

Grekou, D. and H. Liu. 2018. The Entry into and Exit out of Self-employment and Business

Ownership in Canada. Analytical Studies Branch Research

Paper Series, no. 407, Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 11F0019M. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/11f0019m/11f0019m2018407-eng.htm

Grekou, D., J. Li and H. Liu. 2018. “The Measurement of Business Ownership by Gender in the

Canadian Employer–Employee Dynamics Database.” Analytical Studies: Methods

and References, no. 017, Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 11-633-X. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/11-633-x/11-633-x2018017-eng.htm

Grekou D. and Gueye B. (2021). “Who are the Men and Women Entering Business Ownership in

Canada?” Analytical Studies Branch Research Paper Series, no. 459,

Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 11F0019M. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/11f0019m/11f0019m2021002-eng.htm

Gueye, B., A. Lafrance, and J. Oyarzun.

(2022). Identifying Indigenous business owners and

Indigenous-owned businesses. Analytical Studies:

Methods and References Statistics Canada Catalogue no.

11-633-X no. 045 Ottawa: Statistics Canada. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/en/pub/11-633-x/11-633-x2022008-eng.pdf?st=RVR4G7rc

Innovation, Science and Economic

Development Canada (2019). Key Small Business

Statistics.

Innovation, Science and Economic

Development Canada. (2020). SME Profile: Ownership

demographics statistics.

Leung D., Y. Ostrovski and G. Picot

(2018). “The Financing of Immigrant-owned Firms in Canada,”

Analytical Studies Branch Research Paper Series, no. 404. Statistics

Canada Catalogue no. 11F0019M, Statistics Canada. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/11f0019m/11f0019m2018404-eng.htm

Li, P. S. (2001). Immigrants’

Propensity to Self-Employment: Evidence from Canada. The

International Migration Review, 35(4), 1106–1128. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3092004

Lin, Z., G. Picot and J. Yates (2000), “The Entry and

Exit Dynamics of Self-employment in Canada,” Analytical Studies Branch Research

Paper Series no. 134, Statistics Canada catalogue no. 0-660-96130-X. The Entry and Exit Dynamics of Self-employment in

Canada – ARCHIVED (statcan.gc.ca)

Morgan, H. M., Sui, S., and Malhotra, S.

(2021). No place like home: The effect of exporting to

country-of-origin on the financial performance of immigrant-owned SMEs. Journal of International Business Studies, 52(3), 504–524.

Ozcan, B. 2011. “Only the lonely? The influence of

spouse on the transition to self-employment.” Small

Business Economics 37(4): 465–492.

Rezai, M. R., Maclagan, L. C., Donovan,

L. R., and Tu, J. V. (2013). Classification of Canadian

immigrants into visible minority groups using country of birth and mother

tongue. Open Medicine Journal, 7(4), e85–e93.

Shinnar, S.R. and C.A. Young. 2008. “Hispanic Immigrant Entrepreneurs in Las Vegas Metropolitan

Area: Motivations for Entry into and Outcomes of Self Employment.” Journal of Small Business Management, 46 (2): 242–262.

Statistics Canada, 2001 Census of

Population, Statistics Canada. Catalogue no. 97F0022XCB2001005.

Statistics Canada, 2016 Census of Population. Statistics Canada. Catalogue no.

98-400-X2016190.

Statistics Canada, 2016 Census of

Population. Statistics Canada. Catalogue

no. 98-400-X2016191.

Statistics Canada, 2016 Census of

Population. Statistics Canada. Catalogue

no. 98-400-X2016192.

Statistics Canada, 2016 Census of Population. Statistics

Canada. Catalogue no. 98-400-X2016286.

Statistics Canada. Table 98-10-0303-01 Citizenship by visible minority and

immigrant status and period of immigration: Canada, provinces and territories

and federal electoral districts (2013 Representation Order)

Statistics Canada. Table 98-10-0435-01 Labour force status by visible minority,

highest level of education, major field of study (STEM and BHASE, summary) and

immigrant status: Canada, provinces and territories, census metropolitan areas

and census agglomerations with parts.

Statistics Canada. Table 98-10-0439-01 Employment income statistics by visible

minority, highest level of education, immigrant status and income year: Canada,

provinces and territories, census metropolitan areas and census agglomerations

with parts.

Statistics Canada (2019a). Canada’s Black population: Growing in number and diversity.

Statistics

Canada [Infographic]. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/11-627-m/11-627-m2019006-eng.pdf

Statistics Canada (2019a). Diversity of the Black population in Canada: An overview. Ethnicity, Language and Immigration Thematic Series.

Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 89-657-X. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/89-657-x/89-657-x2019002-eng.htm

Statistics Canada. Table 33-10-0351-01 Reasons business or organization did not

access any funding or credit due to the COVID-19 pandemic, by business

characteristics, second quarter of 2021. DOI: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=3310035101&request_locale=en

Wagner, D., K. Head and J. Ries. 2002.

“Immigration and the trade of provinces.” Scottish Journal of Political Economy 49 (5): 507–525.