MONROE COUNTY, Iowa — No roads lead to Buxton anymore.

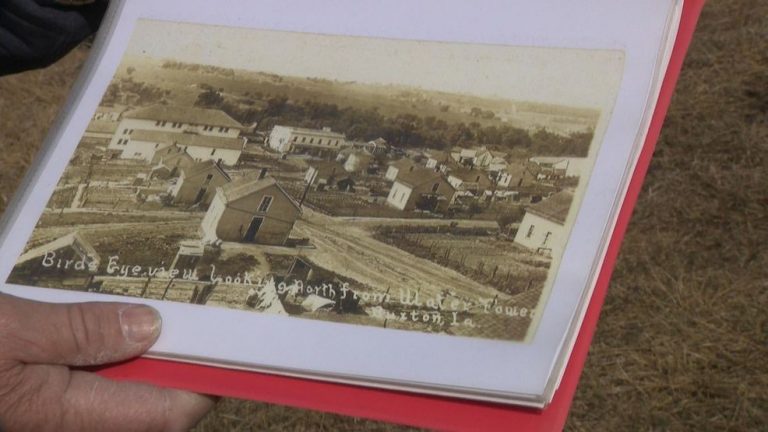

A few battered foundations and quiet farmland are all that mark what was once a bustling coal community, founded around 1900 by the Consolidation Coal Company.

In its heyday, Buxton saw Black men, many arriving as strikebreakers, living side by side with white immigrants hailing from places like Sweden, Slovakia and the British Isles—an arrangement that defied the strict racial divides common elsewhere in early 20th-century America.

For decades, the site drifted into obscurity.

“At one time this was the largest unincorporated town west of the Mississippi,” said landowner Jim Keegle, whose family purchased part of the old Buxton property in 1949. Keegle offered Iowa’s News Now a tour of what remains of Buxton.

A glimpse of a different era

Many first-time visitors are taken aback by how empty the place is, Keegle said. Once, however, this patch of Iowa soil teemed with homes, schools, a sprawling company store and even the country’s boys-only YMCA, equipped with a roller-skating rink that doubled as a dance floor for adults on weekends.

According to Rachelle Chase, who has authored two books on Buxton history — Creating the Black Utopia of Buxton, Iowa and Lost Buxton — Buxton’s African American residents arrived from the South, some not even sure what they were signing up for.

“There was one resident that stated he thought he was coming to work in a gold mine,” she explained, lured by jobs paying the same rates as their white colleagues.

“It was for business reasons. But they said, ‘You know what, we’re going to treat people equally,'” Chase said. “You had Black and white students going to the same schools, being taught by Black and white teachers. You did have 40 to 55% of the population being Black. That just wasn’t happening in most of America.”

Forgotten foundations in the fields

Today, few traces remain to prove Buxton was ever more than farmland. Keegle inherited the land from his grandmother and uncles, who bought it from the grandson of Hobart Armstrong, a black miner turned successful Buxton business owner, after the town’s closure.

Pointing to lumps of limestone under the grass, he said, “This foundation has been here forever. Time has kind of been pretty tough on some of it.” He pointed out a partial wall that once belonged to the White House Hotel, explaining, “They had buyers from St. Louis, Chicago, Omaha, and they would stay here.”

Yet the physical setting is starkly quiet. “I guess it’s just amazing that 125 years ago, you were in the middle of a city,” Chase said.

Meanwhile, some visitors have come long distances to locate ancestors’ gravestones. Keegle recalled one woman from Des Moines who discovered her aunt’s marker. “They took rocks home.” He also recalled an older woman from Florida.

“Until you see a 75-year-old lady on the ground with her arms around a tombstone, that’s the part that gets you, that’s why I keep doing this,” Keegle said.

Felicite Wolfe, curator at the African American Museum of Iowa, noted that many hope to find diaries, store ledgers, or personal documents that reveal daily life. “What I would really love to have been found in Buxton,” Wolfe said, “is more of the paper material, even diaries of a homemaker. That would be amazing.”

But surviving records are minimal.

Stories carried by the wind

Despite that scarcity, oral histories from former residents paint a clear picture of cooperation across racial lines.

According to Wolfe, “Integration was not the norm at the time. African Americans were facing a lot of violence, a lot of segregation in other areas of the country, so to have the opportunity to come to Buxton, it was kind of what a lot of people call the ‘Black man’s utopia.’”

Chase explained that the Ku Klux Klan had a strong presence in nearby communities but never gained traction in Buxton. She attributed that peace to Consolidation Coal’s policies: “Numerous residents did talk about there being Klan activity in the surrounding communities and cross burnings, but that pressure never came into Buxton. The Consolidation Coal Company was very profitable and so it would not have been tolerated should any outside forces in.” She cited stories of John Emery Buxton arming miners and telling them to guard the town. “And that was a business consideration,” she said.

Company oversight also shaped economic life. The multi-story company store stocked everything from groceries to coffins, employing Black and white clerks in the same aisles. Women, including Black women, were just as integrated in Buxton, using these opportunities to run restaurants or work as pharmacists—Chase said Hattie Hutchinson was the only Black pharmacist in Iowa at that time. Buxton, by these accounts, was bustling enough to support baseball teams and large gatherings at the YMCA.

A legacy left behind

Buxton collapsed as quickly as it rose, largely because the coal seams ran dry.

According to Chase, “They literally packed the town up, it was a coal mining town, when the mines played out, they moved operations to further out.”

Residents were scattered, often ending up back in segregated systems. “You had this freedom, now you’re going somewhere else, and they’re saying, ‘You can shine shoes, you can work as a domestic,’ or you have to go to segregated stores and theaters,” she said.

For people like Chase, who first visited the overgrown site in 2008, the fascination with Buxton has become a full-time project.

“I just could not believe such a town existed here literally, in Iowa, in the middle of cornfields,” she said.

She said she is now working on a third book on Buxton, driven by a desire to preserve stories that might otherwise be lost. “The daunting part is making sure that you get the stories right, so much of it is not necessarily documented,” she said.

Keegle, meanwhile, is another steward of that hidden history. “It’s the human stories of people that come back and want to see where Grandma or Grandpa lived,” he said. “If I’m able to show them, well, that makes them happy.”

Today, large-scale efforts to restore or memorialize the site face steep costs. While local historians have occasionally proposed projects, Keegle said funding has never materialized.

Still, visitors arrive, determined to reconnect with a vanished town, keeping this place is more than a footnote in Iowa’s coal mining past, but rather proof of what can happen “when you take race and discrimination out of the equation,” said Wolfe. “It’s a simple idea, but even today, it’s not reality.”