Responding to the prospect of decent jobs in the booming railroad, manufacturing and meatpacking industries, many Black Southerners migrated north at the start of the 20th century, hoping to escape Jim Crow — only to see a Midwestern mutation of that racist system take hold.

Between 1910 to 1950, Black Hawk County’s Black population grew from 29 to 2,623, or roughly 2.5 percent of all county residents. Almost from the beginning, many business owners excluded Black customers, while public pools and the Cedar River beach enforced whites-only swimming.

Rev. I.W. Bess, who founded Waterloo’s first African Methodist Episcopal Church, led the opposition to restricting the beach, but in 1914 the city council voted to impose racial segregation.

In 1916, Waterloo’s Board of Realtors asked the city council to prohibit the sale of homes to Black people in white neighborhoods. The realtors were rejected, but enforced the ban anyway, informally. Race-based housing covenants and redlining abounded. Racism fueled segregation, and segregation fueled racism.

“In the 1920s, city planners intentionally confined Waterloo’s vice district, ‘Smokey Row,’ to Black neighborhoods north of the river,” according to the University of Iowa’s Mapping Segregation in Iowa research project. “White residents, following the lead of local newspapers, used this to sustain a stereotype of Black criminality and immorality. Such stereotypes, in turn, heightened white fears, including the conviction that African American occupancy destroyed property values.”

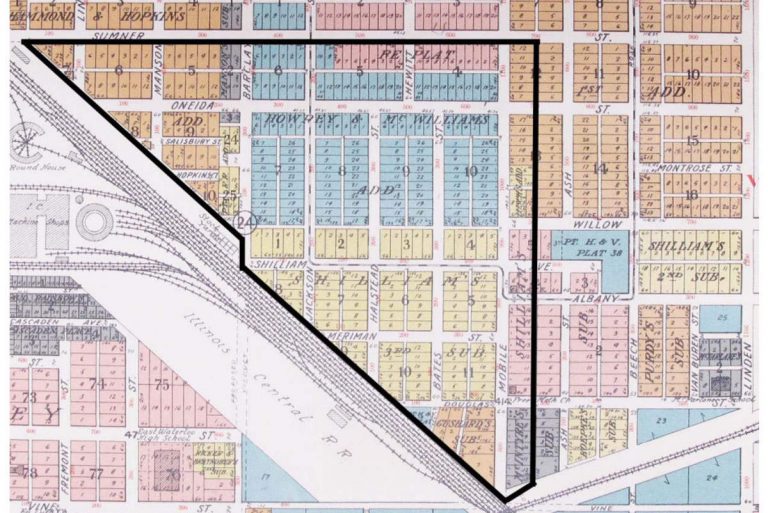

Smokey Row, also called the Black Triangle, was located in east Waterloo, with Sumner Street to the north (expanded to Newell Street in the ’50s), Mobile to the east (later Linden) and the Illinois Central rail lines to the southwest. The area already contained the city’s pool halls, brothels and speakeasies when it was designated as the only neighborhood for Black residents.

Despite institutionalized discrimination — a legacy that haunts Waterloo to this day, and saw it top the list of “worst cities for Black Americans” by 24/7 Wall Street in 2018 — Triangle neighbors were able to blow some of the smoke away from the Row, building churches, political clubs, fraternal organizations and other centers of culture and activism. In the 1940s, Dr. Lee Furgerson, the only Black doctor in Waterloo for many years, Milton Fields, the city’s most prominent Black attorney and founder of the Waterloo chapter of the NAACP, and Judge William Parker, the county’s first elected Black judge, worked together to establish the Black Hawk Savings and Loan Association to encourage homeownership in the Black community.

A large, integrated chapter of the United Packinghouse Workers of America (UPWA) union, Local 46, formed among the multiracial blue-collar population. A massive strike of Rath Packing Company workers in 1948 escalated after the fatal shooting of a Black scab by a white striker, a riot after his arrest, and the deployment of 800 National Guardsmen on Waterloo by Iowa Gov. Robert Blue.

The strike failed. The shooter was found not guilty of manslaughter by a jury, but several union officials were charged with criminal conspiracy for the strike and riot, including local organizer Russell R. Lasley. That didn’t stop him from being elected vice president of the UPWA international union less than a month later.

From that position of power, Lasley, a white man, continued to fight for fair contracts for Rath workers in Waterloo, and went on to head an anti-discrimination department in UPWA. He was part of the 1957 meeting that formed the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, led by Martin Luther King Jr., and went on to serve on its board of directors.

Anna Mae Weems, another union organizer at Rath, emerged as an important civil rights leader in and beyond the Cedar Valley. When she died in September this year at age 98, Weems was hailed as an iconic leader for racial justice and an outspoken idealist. She personally broke many barriers, becoming the first Black woman to work in several previously all-white spaces, and was also the first Black woman to serve as director of the Iowa Workforce Center.

For more information on the Black Triangle/Smokey Row and redlining in Iowa, explore the UI Mapping Segregation project and the University of Northern Iowa’s African-American Voices of the Cedar Valley Oral History Project, both online and free to access. Other rich sources: the African American History Museum of Iowa, newly renovated in Cedar Rapids’ Czech Village/New Bohemia; the African American Historical and Cultural Museum in Waterloo; and, for local 4th and 5th graders, the 1619 Freedom School program. For more background on Lasley and the UPWA strike, see local historian Pat Kinney’s writing at groutmuseumdistrict.org.

This article was originally published in Little Village’s December 2024 issue.