The Federal Aid to Highways Act and The National Historic

Preservation Act, both passed in 1966, had provisions to protect

natural habitat, park and recreation land, and historic

buildings. Those laws became vehicles for activists to delay

the Leakin Park, Federal Hill, and Fells Point sections of the

broader expressway system plans in court. Preservationists

got Fells Point placed on the National Register of Historic Places

in early 1969. Federal Hill won the designation a year later.

Both neighborhoods, then and now majority-white, would ultimately

be saved.

“The national highway system was truly a great American

achievement, that was Eisenhower’s plan,” Mikulski says.

“However, the Robert Moses approach, his vision destroyed

neighborhoods so he could create other neighborhoods.”

Several cities Mikulski is referencing—New York, Boston,

San Francisco, Oakland, Milwaukee, Chattanooga, Providence—have already converted urban expressways to more

neighborhood-friendly boulevards. Others are in process.

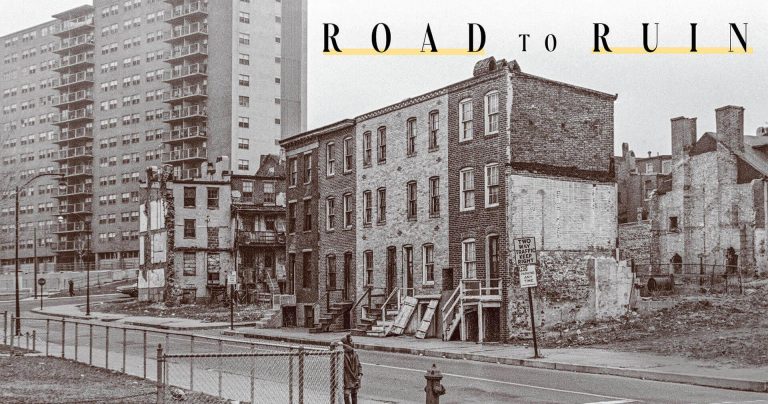

The tragedy is the city’s long effort to link the east-west

expressway to I-70, I-95, and I-83 was all but dead by 1974,

when then-Mayor Schaefer gave the final go-ahead to build

the now pointless 1.39-mile spur. Relatedly, Schaefer’s and

city leaders’ obsession with building highways through the

city is the reason Baltimore doesn’t have a full Metro system

like Washington, D.C., which did not have a thriving downtown

like today when planning began for that project in 1967.

“It was well beyond the time when a reasonable person

would have said, ‘Wait, it’s time to reevaluate,’” says Evans

Paull, a former city planner and author of Stop the Road: Stories

from the Trenches of Baltimore’s Road War. (See our full interview with Paull, here.)

“[He] was also a very strong pro-business

guy, and the Greater Baltimore Committee was the

No. 1 cheerleader behind the highway plan. . . . The

irony is that if the city business interests advocating

for highways had been successful, it would’ve

been economically disastrous for the city. The later

redevelopment of all those [Inner Harbor] neighborhoods

might not have happened if the highways

been built.

“I also don’t think the city would have ever entertained

an expressway through a comfortable

middle-class white neighborhood, the way it did

Rosemont, for example,” continues Paull. “I think

it’s just characteristic of the city’s low regard for African-

American neighborhoods that it was the only

section that got built in the end.”

To his point, just this summer, after an 18-year

battle with the city, Sonia and Curtis Eaddy saved

their rowhome, which sits a block south of the

Highway to Nowhere, from demolition. The city first

sent a condemnation notice to the Eaddys back in

2004, along with more than 100 of their Poppleton

neighbors, including dozens of homeowners. Baltimore

officials had decided to clear out the neighborhood

for a University of Maryland expansion and a

New York-based company’s proposed development.

The Eaddys’ struggle was part of a broader successful

community campaign to preserve a small

block of distinct 19th-century rowhouses around

the corner from their home on Sarah Ann Street.

Unfortunately, those residents were all forced to

leave before the homes were finally designated offlimits

and safe from development. Only a few, if

any, are likely able to return.

“My dad grew up in this block,” says the 57-yearold

Sonia Eaddy. “He was at 329 Carrollton Avenue and I’m 319. He bought his house in 1969 or 1970, and that’s where I

grew up. ‘The Highway’ was up the corner. My grandmother and grandfather

moved to the 1200 block of Mulberry, across the street, so as a

kid, I remember when the city demolished their property. I remember

the gravel, the metal poles with the wire surrounding the blocks that

were demolished. We used to play on those lots and throw rocks. Then

when they started to dig, you had to take what we called ‘the bridge’

across to see friends, go to school or church, or go to Edmondson Avenue,

which had a lot of shops.

“I was young, I can’t speak directly to how people felt about the

city condemning their property at the time,” she continues, “but with

our home and the Sarah Ann Street homes, it was basically like, ‘You

don’t count. You don’t matter.’”

There are also historical echoes between the building of the Highway

to Nowhere and the cancellation of the Red Line.

Just two months before King’s assassination and the riots in Baltimore,

Mayor Thomas D’Alesandro III—in an address to the American

Road Builders Association, no less—acknowledged the dark truth that

the planned expressway, “will displace thousands of families, will

dismember neighborhoods and communities, will disrupt industry

and commerce, and will destroy parks and historical landmarks.” The

Little Italy native, whose father had been mayor when the east-west

expressway plans were first hatched, added that “the problem of dislocation

of people is particularly critical.” He even forewarned the

dislocations would become “a major cause of unrest.”

Nonetheless, as Paull highlights in his book, only two weeks after

the riots, D’Alesandro decided to stick with the final expressway design

that would devastate the Franklin-Mulberry corridor.

In an analogous gut-punch to a reeling West Baltimore, Governor

Hogan announced his decision to defund the Red Line two months

after the uprising following Freddie Gray’s death. At the same time, he

said he would increase infrastructure spending on roads and bridges

by $1.35 billion—“from Western Maryland to the Eastern Shore.”

At a 2015 news conference, Hogan defended, at least in part, his

decision this way: “We just spent $14 million extra money on the riots

in Baltimore City a few weeks ago.”

Thirty years earlier, in the mid-1980s, Schaefer, on the cusp of

running for governor, approved a deal that sent $261 million of the

last of the unused city-expressway funding back to the state. Part of

that money was used for an I-68 project in Western Maryland. History,

as they say, may not repeat, but it often rhymes.