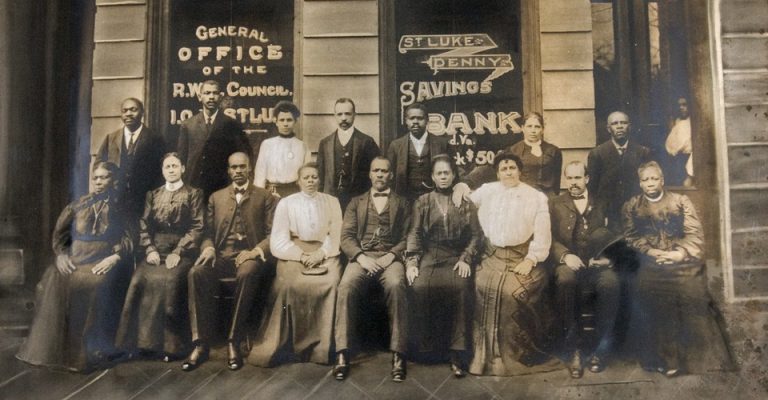

The decline raises the question of whether these niche banks still have a place in modern America. I visited the Jackson Ward neighborhood of Richmond, Virginia, once dubbed America’s “Black Wall Street” and “the birthplace of black capitalism.” At the turn of the 20th century, it was one of the most prosperous black communities in the United States, with thriving theaters, stores, and medical practices. Richmond is where the first black banks opened, including one chartered to a former schoolteacher named Maggie Walker—the daughter of a freed slave. The St. Luke Penny Savings Bank, which Walker opened in 1903, made loans to qualified borrowers who were shunned by traditional banks, such as black doctors, lawyers, and entrepreneurs. St. Luke’s would eventually merge with other black banks and become Consolidated Bank and Trust. By the end of the 20th century, the bank was the last black-owned bank in Richmond and was struggling to compete with much bigger banks downtown. It had several troubled loans on its books and couldn’t raise enough capital to stay afloat. In 2005, a Washington, D.C.-based bank bought it, then a West Virginia-based bank took over in 2011 and renamed it Premier Bank. The last bank of “Black Wall Street” was gone.

Premier’s president, Darryl “Rick” Winston, says he too wonders what role black banks will play in the future. He once reviewed loans at Premier Bank when it was still the black-owned Consolidated Bank and Trust. At one point, he says, the bank had $111 million in assets and seven branches. Winston, who is African American, left for a consulting job in 2000, and returned last year to take over as regional president after the buyout. Winston drove me around Jackson Ward, pointing out the shuttered businesses that once made Richmond a bastion of black wealth and culture. “Duke Ellington and Louis Armstrong stayed there,” he said, pointing to the former site of the Eggleston Hotel, one of the few upscale lodgings for blacks in the Jim Crow south. As we drove by, a construction crew was busy building a mixed-used complex that will house 31 apartments, 10 townhomes, several stores, and restaurants.

Two blocks away, Premier Bank remains in the same brick building as its predecessor. Much of the bank’s staff is the same. Winston says it’s important to make sure his employees reflect the community they serve, even if it’s no longer a black-owned institution. That’s in part because African American borrowers still face immense bias in the banking and lending industry, he says. “It’s more subtle. A black person goes into a mainstream bank and the loan officer might think of rejecting their application before it’s even complete,” he says.

Racial bias in the lending industry remains all too common, despite legislation aimed at preventing it. In 1992, a landmark study from the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston examined 4,500 mortgage-loan applications and discovered that black borrowers were twice as likely to get rejected for loans than white borrowers with similar credit histories. More recently, an economics professor at the University of Massachusetts found that banks in Boston and across the state of Massachusetts continue to reject black and Latino borrowers for home mortgages at a much higher rate than whites.