Every February, during Black History Month, people in the United States celebrate the achievements and history of African Americans. Black History Month is a time for recognizing African Americans’ central role in U.S. history.

How It Began:

Black History Month was the brainchild of famous Black historian Carter G. Woodson in 1915. Woodson created Black History Month, also known as African American History Month, because there was a lack of information on the accomplishments of Black people and their contributions to U.S. history available to the public.

(Photo Dr. Carter G. Woodson courtesy Wikipedia.)

As a result, Woodson, who was Harvard-trained, and Jesse E. Moorland co-founded the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History, according to the History Channel. However, it wasn’t until years later, in 1926, that the group declared the second week of February as “Negro History Week.” They chose that week in honor of the birthdays of both Frederick Douglass and former U.S. president Abraham Lincoln.

Other countries such as Canada, Germany, Ireland, the U.K. and the Netherlands have joined the U.S. in celebrating Black people and their contribution to history and culture. However it’s observed in October in the U.K. and Ireland.

Las Vegas’ Black History:

A famous quote from Mya Angelou says, “I have great respect for the past. If you don’t know where you’ve come from, you don’t know where you’re going.” So when it comes to Black History in Las Vegas, we have to start where it all began — The Historic Westside.

While the Westside was struggling to provide adequate housing for its growing population during the 1940s, the business community in the neighborhood was thriving. African Americans helped to establish a prosperous community of minority-owned businesses in the Westside after being forced out of downtown and excluded from the economic boom occurring on the Las Vegas Strip. West Las Vegas developed its own grocery stores, gas stations, nightclubs, barbershops, liquor stores and other retail businesses that fostered a vibrant minority community during the 1940s and 1950s. Although businesses were spread throughout the Westside, the heart of the African American business district was Jackson Avenue, locally referred to as “Jackson Street.” The street was also known as the “Black Strip” because of the many nightclubs and hotels that catered to a largely African American clientele.

In addition to the commercial development taking place in the Westside, religion also formed the backbone of the community’s post-war development. The organization of churches was one of the chief activities of African American immigrants arriving in Las Vegas. During its heyday in 1940s and 1950s, the Westside had more churches per square mile than any other section of the city

Many of the most sought-after acts for resort shows were African Americans like Sammy Davis Jr., Lena Horne, Nat King Cole, Dinah Washington and Dorothy Dandridge, to name a few. But they still couldn’t gamble, attend shows or stay in hotels where they performed.

(Photo of Sammy Davis Jr. and friends courtesy Vintage Vegas.)

Due to the casino owners’ policy, the entertainers would perform their acts before they were ushered out the door, forced to stay, party and dine off the Strip. The same rules applied to tourists and locals.

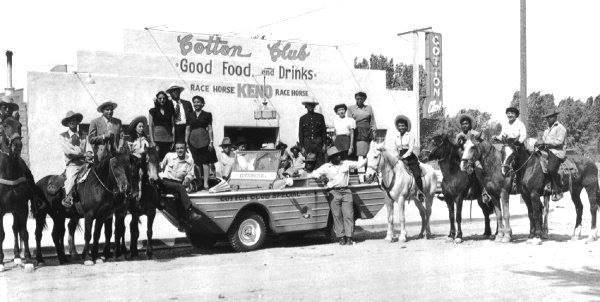

Out of the segregation of the Strip was born Black-owned hotels and clubs on the Westside. According to the Las Vegas Review-Journal, in 1947, the Brown Derby, the Cotton Club, The Chickadee and the Ebony Club opened on Jackson Street.

(Photo of the Cotton Club courtesy Vintage Vegas.)

By 1955, with Las Vegas’ resort industry and the number of associated jobs expanding rapidly, the city became home to more than 15,000 African Americans, PBS said.

Fast forward to May 24, 1955, when the first integrated hotel-casino in Las Vegas opened its doors on the Westside. It was called The Moulin Rouge Hotel and it quickly became a landmark.

(Photo of the Moulin Rouge Hotel courtesy Vintage Vegas.)

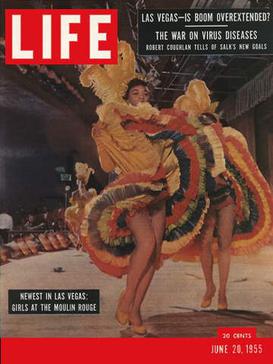

It boasted some of the same amenities as resorts on the Strip including, gourmet food, a pool, a casino, a lounge and a showroom. The Moulin Rouge was even featured on the cover of Life Magazine on June 20, 1955.

(Photo of the Moulin Rouge featured on Life Magazine courtesy Wikipedia.)

The Moulin Rouge’s life on the Westside was short-lived because it closed later that year when the owners filed for bankruptcy in December 1955, but many credit the hotel’s successful integration as a catalyst to help usher the city into full-blown integration. But it didn’t come without a push and nudge.

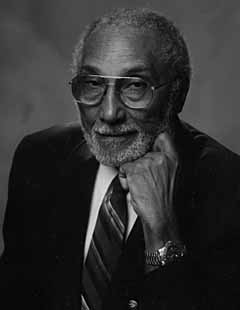

In early 1960, Dr. James McMillan, the President of the Las Vegas chapter of the NAACP, gave Las Vegas authorities an ultimatum: Desegregate within 30 days of his announcement, or he would stage a citywide protest. African American entertainers also refused to perform unless they were allowed to stay in the resorts and fellow African Americans were allowed in the audience of their shows.

(Photo of Dr. James McMillan courtesy the Las Vegas Review-Journal.)

According to PBS, on March 25, 1960, the day before McMillan’s scheduled protest, he and other NAACP members met with the mayor of Las Vegas and essential businessmen in the city to broker an agreement. The meeting was mediated by Hank Greenspun, the editor of the Las Vegas Sun at the time.

PBS said the group worked out an agreement that lifted all Jim Crow restrictions and desegregated the city. As a result of the deal, which became known as the Moulin Rouge Agreement, Jim Crow restrictions were lifted, desegregating the town.

Black Americans were now allowed to gamble, stay in resorts and attend shows in Las Vegas.

Listen to the Black History month Twitter Spaces, “A Conversation with Some of Las Vegas’ Influential & Inspiring African American Leaders,” below.

In 1971, a little over a decade later, Las Vegas’ housing codes were modified to prevent redlining. This came from federal bills such as the Fair Housing Act of 1968.

For more on some of the movers and shakers in Las Vegas and the Historic Westside, go here to learn more about our Legacy Park honorees.