Conservationists in New York are ramping up research and preservation efforts of a historic Black community that had all but disappeared, illuminating what some experts say is an “antidote” to ongoing rightwing efforts to keep African American studies out of classrooms.

Weeksville, New York, located in present-day Crown Heights and Bedford-Stuyvesant, had been a center of Black excellence since its founding by a dock worker named James Weeks in 1827. A copy of the New York Times from 1855 advertised “beautiful building lots at Weeksville” for between $130 and $200 cash under the heading “For Sale To Colored People.” It was a thriving community of free Black people who escaped slavery in the south.

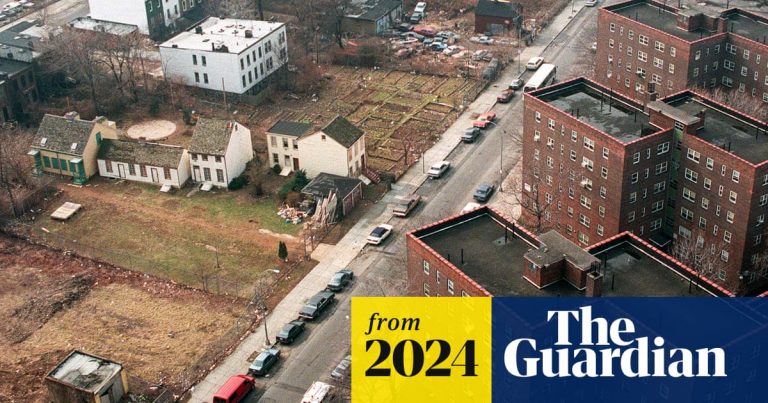

For decades, the community was the center of Black life in Brooklyn – much like Harlem would become in Manhattan. Residents moved from all over, from the Caribbean and Africa, but after a few decades of burgeoning all-Black businesses, churches, schools and homes, Weeksville gentrified. As Brooklyn became a popular place to live, the city street grid was imposed, destroying existing infrastructure, homes and buildings were demolished, property values increased and, block by block, existing residents were pushed out.

Soon, one of the largest independent Black neighborhoods in the US had disappeared to everyone except descendants of the families who lived there. It was “rediscovered” by researchers in the 1960s, who stumbled upon the three old houses that were part of the original neighborhood.

It’s “important to tell the story over and over, especially to young people, to help them understand the history and what it meant to have a free Black community in the post-war era”, Raymond Codrington, president and chief executive officer of the Weeksville Heritage Center, said.

Since its founding in 1971, the Weeksville Heritage Center – previously known as The Society for the Preservation of Weeksville and Bedford-Stuyvesant History – has been leading the conservation efforts of this historic neighborhood, but it’s been severely underfunded for much of that time. In 2021, it became the first institution added to New York City’s venerable Cultural Institutions Group since 1997, joining the ranks of Carnegie Hall and the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and opening up new city funding streams.

This additional funding has given conservationists the chance to preserve the thousands of historic artefacts they have collected since the 1960s, including family heirlooms, clothing, photographs, letters and household items, many of which have been in boxes for decades. Staffers aren’t even sure of the exact number of items in their collection.

“It’s wonderful,” the historian Judith Wellman said upon hearing the news.

Wellman is one of the world’s leading experts on Weeksville, and the author of Brooklyn’s Promised Land: The Free Black Community of Weeksville, New York, published in 2017. She faced extreme challenges in doing research on Weeksville for her book because, with the exception of the town schoolteacher who was also a journalist, “nobody wrote anything down”. She’s hopeful new information will come from the yet to be plumbed collections – as is the staff at the Weeksville Heritage Center.

Codrington emphasizes that learning this history is “essentially the antidote to what’s going on in places like Florida”, referring to Governor Ron DeSantis’s efforts to ban African American studies from Florida high schools.

“Especially in this period that we’re in, when we are discouraged or being prevented from teaching Black history, talking about Black culture in specific ways,” he said. “When you have a history like Weeksville, it becomes even more important to tell those stories.”

The work to tell that story is ongoing. There are efforts to call the community “Weeksville” once again, including on real estate sites such as StreetEasy. The heritage center also offers tours for school groups and tourists through the original homes, called the Hunterfly Road Houses after the Indigenous trading route they sit upon. eThe homes are set up as if the original Weeksville families were still living there, using historical artefacts from the heritage center’s collections.

“It is a space where you can learn about Black history and culture and you can actually experience it by going into the houses,” Codrington said. “There’s something about history tied to objects. I think some people are different types of learners. Some people need to see stuff. Some people need to see artefacts. Some people need to see objects.”

It’s those objects, especially household items, Codrington notes, that can help create a connection between diverse audiences.

“When people connect with the history and see the space, oftentimes I think they leave with different sense of self because they situate themselves and their family in relation to what was going on weeks from at the time,” he explained, adding Weeksville was “a very specific African American story, but then also other people draw parallels to having these people that on farms, living in rural areas, may have had the same bed. They had a similar cup, something like that. It’s very interesting what resonates with people.”

The Weeksville Heritage Center is still expanding those collections. To spearhead this major undertaking, the center just hired a new collections manager, Suzanne Shapiro.

The collection has plenty of artefacts, some from archaeological digs and others donated by family members who have long ties to the community. One of Shapiro’s favorites – and most consequential finds – is a set of photographs donated decades ago by Percy F Moore that had been buried in the archives.

The photographs were taken by Moore’s uncle and prominent Weeksville resident, Alexander A Moore, sometime in the late 1800s – perhaps as late as 1905. They include portraits, scenes of candid daily life in Weeksville, and group photographs of important civic groups.

“They’re just beautiful documents of the fullness of life in Weeksville that you can just catch these snippets of these people’s lifestyles a hundred plus years ago,” Shapiro said, gently flipping through the boxes of negatives and prints in her light-filled office. “I think we’re all attracted to photography of individuals and the immediacy of just kind of locking eyes with them.”

One photo is a group portrait of the Garnet Field Club, a Black baseball team in Weeksville named after minister and activist Rev Henry Highland Garnet, which Shapiro says demonstrates the success of Weeksville as a community.

“Baseball was kind of seen as the gentleman’s sport at the time,” said Rachel Topping, the marketing manager at Weeksville Heritage Center. “Sophisticated folks played baseball, and there were some news articles at the time that were noting … a level of astonishment from the larger community that Weeksville was ‘civilized’ enough to have these teams.”

Shapiro and the Weeksville Heritage Center want to catalog the rest of the Moore photo collection and the more than 7,500 items in their collection. They will undertake another round of fundraising this year to support that work.

“One of the important things is not only to maintain the legacy, but then build on the legacy and think about how is this story still relevant today?” Codrington said.

“Notions around or questions around citizenship, democracy, self-determination, neighborhood change, all the reasons why Weeksville was created in the face of racism, we’re dealing with some of those same issues today. It’s interesting space for us to occupy and yeah, we hold that. We take it very seriously.”

-

This story was amended on 24 January 2024 to clarify that the Weeksville Heritage Center, at that time known as The Society for the Preservation of Weeksville and Bedford-Stuyvesant History, was founded in 1971, not 2013, which is the year it opened to the public; and to correct that it was Rachel Topping, not Suzanne Shapiro, who said baseball was seen as the gentleman’s sport at the time.