But efforts underway in the Ocean State now seek to shed light on its past, and they’re already impacting how some young Newporters interact with the city they call home.

A few blocks from the cobblestoned downtown thoroughfares and not far from the perfectly preserved Gilded Age mansions that visitors flock to, a mostly empty parking lot catches the eye of Gabrielle Brown.

The high schooler learned during a freshman-year history course that the site is rumored to have once been an enslaved African woman’s bakery. Taken from West Africa and brought to Rhode Island in the 18th century, Charity “Duchess” Quamino became known as the city’s “Pastry Queen” for her catering business that, some say, served George Washington during a local visit — and eventually bought her freedom.

The teen pauses to picture Quamino’s day-to-day routine.

“I just stood there and imagined what it would have been like as a bakery … trying to imagine what life was like then for Black people in Newport,” she said.

The stories of Black residents and business owners in Newport aren’t in the state’s history textbooks.

But in 2021, Governor Dan McKee signed into law a bill requiring that schools include teachings on Rhode Island’s “African Heritage History” by the 2022-2023 school year. Advocates call it among the most comprehensive efforts nationwide to teach local Black history. Now, districts across the state are striving to incorporate lessons like the one that inspired Brown to envision a past about which she otherwise may never have learned.

The move comes as conservative activists — in Rhode Island and across the nation — rally to curtail classroom lessons around race. For Clark-Pujara, author of “Dark Work: The Business of Slavery in Rhode Island,” Rhode Island’s African heritage efforts are a step toward learning about histories that have been “intentionally disremembered.”

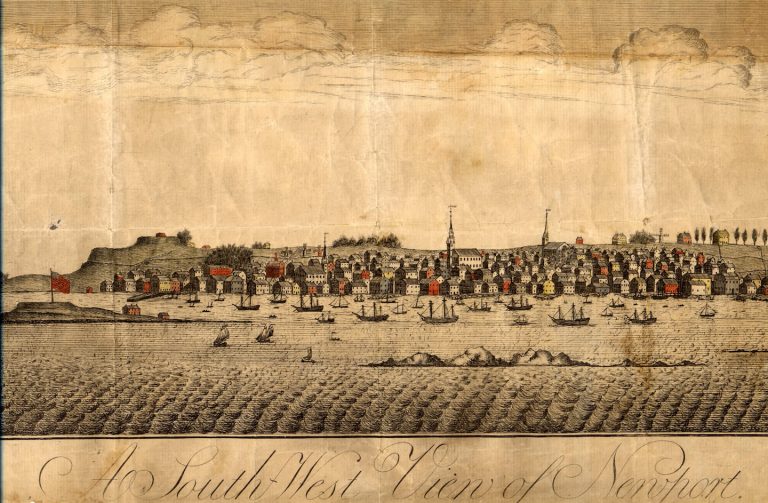

Some 60 percent of all slave trading voyages that launched from North America — amounting to 945 trips between 1700 and 1850 — began in tiny Rhode Island. In some years, it was more than 90 percent and most of those journeys set out from Newport, making it the most trafficked slaving port of origin on the continent.

“The streets of Newport were paved with the duties paid on enslaved people,” Clark-Pujara said. “You have an entire economy that is wrapped up in the business of slavery.”

Although the city of 25,000 people is now more than 80 percent white and only 8 percent Black, in the mid-1700s, approximately a quarter of Newport’s population was Black or African, the second-highest share in the United States at the time behind Charleston, South Carolina. Early Black Newporters were among the first African Americans in the country to attend college, and they launched the nation’s first African mutual aid society.

The steps toward reckoning with the city’s historical role in the slave trade come on the heels of decades of silence.

“It’s never been taught,” said Victoria Johnson, 81, who was a longtime teacher and eventually became the state’s first black female principal before retiring from Newport’s Rogers High School in 2003.

The pioneering Black educator grew up in a mostly segregated Newport and her memory of the discrimination still stings: being prevented from eating an ice cream cone at the counter of the five-and-dime store where she purchased it, the difficulty of finding a high school job. It wasn’t until college when she stumbled across a document on Newport Gardner, a Black 18th-century Newporter who made a name for himself as a musician, that she began to understand the full history of the city she was raised in.

Later, as an employee of the district, she remembers being required to take a Newport and Rhode Island history course because she attended a university out of state. The course, however, made no mention of African Americans’ contributions. And while she recalls lessons covering the region’s key business exports, they did not touch on the slave trade.

Long retired from the school district, Johnson now helps lead the Newport Middle Passage Port Marker Project, an initiative working to build a public memorial downtown to acknowledge Newport’s role in the slave trade and honor African Americans’ contributions to the city.

“Who was here to build these buildings that are 350 years old? Do you think the English did? Of course not,” she reflected. “The African Americans, the Africans that were here. And nobody ever tells that story.”

“I want people to know that there have always been people of color, there have always been Black people in the city of Newport,” she said.

Akeia de Barros Gomes works as a curator at the Mystic Seaport Museum in nearby Connecticut. Like Johnson, she grew up in Newport, and like her, it wasn’t until de Barros Gomes went elsewhere that she learned the rich history of people who looked like her in the city.

“I didn’t know anything about Black history in Newport until I left and was a grad student and started looking into it as an academic,” she said. “I didn’t get any of it growing up. There are no places on the landscape that indicate that there was any Black history in Newport — ever.”

While researching for her doctorate degree around 2005, de Barros Gomes asked her mother, who was working at a Newport elementary school, to help with an informal educator poll. About two dozen teachers were given maps of Newport with instructions to draw an “X” at any site of Black history. Only one map was returned with any marks at all.

“I was shocked,” said the researcher. “There was room for comments and one of the teachers said, ‘I think that slavery happened here. Maybe.’”

The story is different — at least to a degree — for students and teachers today.

Via public record requests, The 74 obtained curricula, lesson plans and classroom handouts from social studies classes in Newport. Required 10th and 11th grade history courses now include teachings on Black business leaders in Newport and weave in lessons on Rhode Island’s role in the slave trade, the documents show. A ninth grade Black history activity highlights the contributions of 19th and 20th century African American Newporters.

“Our social studies department is committed to incorporating local Newport history and early Black life into the curriculum,” Christopher Ashley, the district’s director of teaching, learning & professional development, told The 74 in an email.

“Our teachers acknowledge Newport’s history in the slave trade and work to help students think deeply about the historical context of Newport and the colonial slave trade overall.”

In 2016, the high school launched a half-credit state history elective, where students can dig deeper into those topics. However, after being offered three years in a row, the district said the course was cut in 2019 because too few students signed up. The high school will decide in August whether it will be taught this fall, said Superintendent Colleen Jermain.

In Newport’s elective course, students explore topics including how the economy of colonial Rhode Island became dependent on the Transatlantic slave trade, and examine sources such as an article describing a back-to-Africa movement pioneered by colonial Black Newporters.

Covering those topics represents “definite progress,” said Clark-Pujara who, in a study for the Southern Poverty Law Center published in 2018, evaluated how textbooks used in Rhode Island cover the Ocean State’s involvement in the slave trade.

After examining the course materials obtained by The 74, the scholar observed that they lacked information on the pushback against enslavement. Teachers can use runaway ads or news reports to highlight those histories, she suggests. Just reading a passage from the diary of an enslaver, she added, is sure to document the ways their human property resisted their conditions.

“Whenever you tell the history of slavery, you must tell the history of resistance. Because there wasn’t a time that it existed without it,” said Clark-Pujara. “It is so damaging to students, and especially to African-American students, to sit in the classroom and just hear about all of the terrible things that were done to Black people.”

Newport’s stand-alone Black history elective may have been sparsely attended because students didn’t know it was

“I didn’t even know we had a Rhode Island History class,” said Dellicia Allen, a rising senior at Rogers.

In ninth grade, Allen received the same lesson that inspired Brown to make a pilgrimage to the parking lot that may have been Pastry Queen Duchess Quamino’s bakery. But the lesson left Allen part gratified, part frustrated.

Her World History teacher had distributed a map of Newport as well as a list of famous Black figures in local history with an article to accompany each person. As students read, they dotted the map with the events and businesses that once took place there.

The activity was interesting, Allen said. But the unit seemed “skimmed over” and not taken seriously, she said.

“All this time, Newport had such a rich history. And in ninth grade … we’re just now even considering it?” Allen told The 74. “We had to wait so long … and [the lesson] lasted for, what, a day?”

Newport Public Schools acknowledge some room for improvement. Their courses are continually evolving to better incorporate local Black history, said Ashely.

State Rep. Anastasia Williams, who sponsored the African heritage history legislation, is proud of the bill but also aware of its limitations: It does not include a way to enforce compliance among school districts, and there’s no funding disbursed by the state for the law’s rollout. Legislators were willing to accept the bill’s provisions in the wake of George Floyd’s murder, she explained, but she doubts it would have passed if it required funding.

“There are still many offsprings of slave owners that live here. … They’re afraid of everybody learning the truth,” she told The 74. “Eyes wide shut.”

Indeed, the history has been buried so deeply that Williams’s past colleague, former Rhode Island Speaker of the House Nicholas Mattiello, infamously stated in 2020 that he didn’t think there was ever “actual slavery” in the state.

“The mentality of slavery remains. It’s almost like dealing with the Jim Crow South,” said Williams, who has served in the State House for nearly three decades.

The Rhode Island Department of Education has yet to plan any professional development sessions to train teachers in the new lessons, set to take effect this fall, acknowledged spokesperson Ashley Cullinane in an email to The 74.

“It would be up to the districts to determine what professional learning is needed,” she wrote.

The state has, however, worked with the Rhode Island Historical Society to develop resources for students and educators, she pointed out.

Those resources show signs of an uptick in lessons on local Black history. Over 22,000 people visited the Rhode Island Historical Society’s modules on local history from July 1, 2021 through June 31, 2022, up from 9,000 the year before, said the organization’s Education Director Geralyn Ducady. Visitors to their page of lesson plans on Black history in Rhode Island jumped from 582 to 773 during that time span.

A simultaneous, opposite push has otherwise-eager educators on edge over lessons that touch on race. Rhode Island has become a hotbed in the nationwide effort to root out suspected teachings on critical race theory, a graduate-level scholarly framework that examines how racism and inequality are ingrained in law and society. Right-wing activists in Rhode Island and beyond have used CRT as a catch-all to attack lessons on race and racism. Three nearby school districts — South Kingstown, Westerly and Barrington — made headlines for buckling under massive record requests from community members suspicious that local classrooms were overstepping in their teachings on race and gender.

Although Rhode Island is not one of the 17 states to have enacted laws restricting such lessons, a bill to do so was introduced by state legislators in spring 2021, though it failed to pass.

“These difficult histories, if taught properly … should inspire empowerment,” said de Barros Gomes. Even if it spurs anger, “that’s a good anger, because it’s an anger that makes me want to do something.”

Niko Merritt is not waiting around as Newport schools scale up their lessons on local Black history.

Her children attend school in a nearby district and she works in Newport to strengthen the local Black community through her nonprofit Sankofa Community Connection. Among many initiatives, Merritt runs a “History and Culture Club” in Newport’s Thompson Middle School and leads youth-friendly Black history walking tours of the city.

Called the “Rise to Redemption” tour, Merritt said her presentations give an uplifting message, each focusing on the life of one historical Black Newporter born into slavery and who, like Duchess Quamino and Newport Gardener, worked to eventually buy their freedom. Participants learn where the figure worked, lived, worshiped and socialized to give a picture of the individual’s full personhood.

“The reason why I wanted to do this tour was because I wanted people to feel seen, and to see themselves here,” said Merritt. “A lot of us feel unseen in Newport.”

After a session with middle schoolers, one student’s feedback stands out in her mind: “I feel like I belong here.”