In the spirit of conservative individualism, he believes that top-down governmental fixes to address inequality can only go so far. He thinks Black communities’ challenges can be solved not with sweeping institutional redistributions like reparations but with internal cultural change and government policies that would promote economic uplift regardless of race. And while Loury has been a critic of mass incarceration, he rebukes progressive narratives about systemic racism that imply American society is purposely keeping Black people in the Jim Crow era. He writes that he believes there needs to be more focus on issues like “the state of the black family, the black victims of violent crime, and the necessity of building social capital within black communities.”

Loury recounts his political evolution in his tell-all memoir, “Late Admissions,” where he also details falling prey to — and overcoming — many of the vices he cites as plaguing Black communities. Loury has mended his relationship with the son he abandoned to a single mother, he’s beaten his addiction to cocaine, and he has gone from being a self-proclaimed “player” and philanderer to a pensive grandfather living in a sleepy part of Providence. The individualism that makes him critical of dynamics he sees in Black communities also makes him hopeful. “I was raised by some of the most industrious people I had ever met,” he writes. “If I believed that black people were lazy or incompetent, it would have made no sense for me to expend so much energy championing the development of their skills and abilities.”

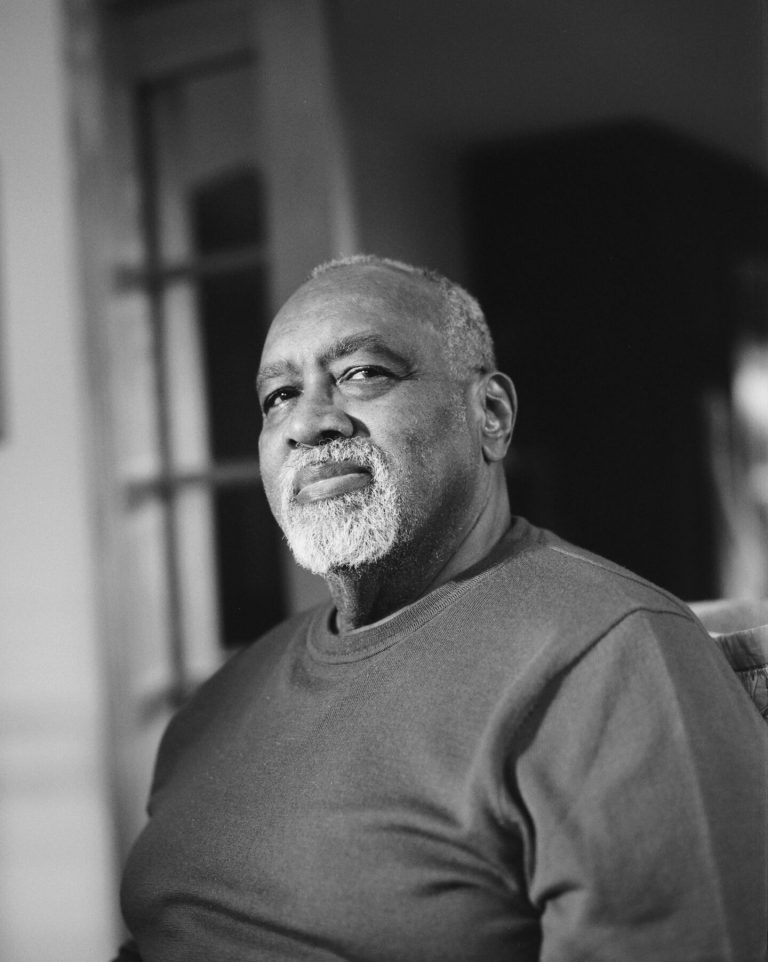

Sitting in his home this summer, Loury and I discussed the apparent contradictions in his life. Some of the quotes that follow have been condensed.

Glenn Loury makes it sound like being a Black conservative is the most natural thing in the world — though not the easiest.

“I talk a little bit about this in the book — about disappointing family members because of my politics and feeling torn between wanting to be an independent thinker and go where my mind leads me on the one hand and feeling that I am in one way or another perhaps being used by people on the right because I’m a rare representative as an African American conservative of a certain type. Or that I’m betraying in some way or another my people and then I’m losing authenticity as a member of the community by sticking [with] a position that so many in the community reject.

“I’m a neoliberal economist and somewhat conservative culturally. I was a born-again Christian at a point in my life. I am no longer a practicing religious follower, but I have great respect for those traditions and for some of the cultural conservatism that comes out of that. But mainly, I think ‘Black conservative’ is a label that sticks to me because I’m a person who believes in personal autonomy and responsibility, and I think African Americans need — we do collectively as a group — to take control of our lives and to not be dependent upon the benefits and transfers and whatnot that come from people who are trying to make up for the past. And I think the imperative in front of African Americans today is an imperative of development, of realizing the potential that has been created by the success of the civil rights movement and the opening up of American society. And that makes me conservative in the sense of the Booker T. Washington side of the Washington-DuBois debate about the future of Black Americans from 125 years ago. I’m on the Booker T. Washington side. In the contemporary times, that’s a relatively conservative position. The way I’ve put it on occasion is to ‘seize the reins.’ The ball is in our court. The train is leaving the station, America is a great open society.

“I think as I get older, it becomes less of a problem to be a Black conservative. Is it lonely sometimes? Yeah. Is it liberating? Sometimes, yeah. So it’s a mixed bag.”

In the aftermath of George Floyd’s death, how did he feel about the ensuing protests and the Defund the Police movement?

“The radicals had control of the agenda. I think there was a kind of moral panic, in which everybody felt that they needed to demonstrate their solidarity with a moral position, which is anti-racism, and took the relatively few incidents of police mistreatment, which were egregious, like the George Floyd incident, and [built them] into a general case against the necessity of policing broadly.

“So you end up with this slogan, and that’s all it is, a slogan about defunding the police. It’s not a coherent vision of how you’re going to secure public safety for people who live in dangerous circumstances. So I thought the rhetoric was not well matched to the reality, and I think the history since 2020 of the Defund the Police movement shows that a) the police haven’t been defunded in many places, although the police have been hampered. But b) the politics of Defund the Police has backfired on the progressives and now Democrats are running away from it. ‘We never said that. That’s not what we meant.’ As well as the fact that the crime issue is going to be not helpful to the progressive candidates politically. I think it’s one of the reasons why Trump is doing as well as he is doing. And I think that some of the problems in major cities across the country, in Los Angeles and in Chicago and New York, in Philadelphia and Washington, D.C., and Atlanta and other places where at the local level they’re seeing spikes in violent crime and property crime, people who have to live with that are expressing their disquiet.” [Editor’s note: Loury is right that violent crime was higher nationwide in 2023 than in 2019, but not all property-related crimes have increased.]

“I think it is in keeping with the commonsense observation that if you attack police officers, you can expect to get less out of the police officers, and the community actually depends upon the police for security and safety. I find it interesting that if I were to be talking about another set of public employees — teachers — and I were to say the conditions under which they work and the extent to which they get affirmed by the society affects their ability to perform their jobs, most people would have no problem with me saying that. And I think something like that is also true about policing.”

In Loury’s memoir, he describes an early 1980s House Judiciary Committee hearing held by John Conyers Jr., a Black Democratic representative from Detroit, about police brutality. Having grown up in Chicago, Loury understood how threatening crime can be for residents of Black neighborhoods and felt that Conyers’s focus on policing was missing the main problem.

“The brutality issues of policing in Detroit were minor compared to the criminal victimization issues that his constituents had to confront. There was an outbreak of rapes of teenage girls trying to get to school in the early morning hours. I use that as an anecdote in the book, to say what was spurring me to question the party line about race and inequality, which Representative Conyers was an exponent of — police brutality, systemic racism. And I was saying, ‘Yeah, but what about criminal behavior? And don’t we owe something to the people who have to deal with the consequences of it?’”

Why did he tell Coretta Scott King that the civil rights movement was over during a meeting with Black leaders in 1984? Does he still believe that?

“The civil rights movement of the 1950s and ’60s and ’70s, if you like, was successful. It was successful at getting the Civil Rights Act and the Voting Rights Act and the Fair Housing Act and so on. It was successful in promoting an ethos that was very different and much more sympathetic to the aspirations of African Americans than was the case in decades earlier. I think the civil rights movement won.

“But let’s say I take the overrepresentation of Blacks amongst criminal defendants — is that a civil rights problem? I don’t think so. I don’t think that’s a civil rights problem that can be remedied by protest demonstrations or the identification of ‘racist’ laws and then getting them off the books.

“Unfortunately, I think it’s a much tougher problem. This is Glenn Loury here, not everybody’s going to sign on to this: that the root of that problem is the behavior of the people who are being brought under the sway of the law enforcement. And that has to do with a lot of things. It has to do with culture and with their family backgrounds and what kind of values are instilled. I’d accept that it also has to do with economic opportunity and what’s going on in the schools and so on. But I don’t think those, either, are largely civil rights issues — that is, issues turning on African Americans being deprived of the full benefits of citizenship.”

While equality under the law may have been achieved, Black communities still face major challenges. Does he see any place for protest? Yes, he tells me — but when the goals are narrow and targeted.

“I don’t mean to pretend that there aren’t some questions about the way in which certain police departments carry on their duties, that there aren’t certain elements within policing that are racist and so on. And you can talk about what kind of accountability and responsibility police officers who abuse their authority or misuse the awesome powers of their office should be confronted with. Citizens review panels about what happens with policing in a particular place — I’m not necessarily opposed to any of that. But I don’t see a major role for protests unless it’s aimed at ‘OK, the schools in the city aren’t working, we want reform. We have an idea about what that reform should be.’ Let’s say it’s a charter school movement or people who want to try to help parents have more voice in what’s going on in the classroom. ‘We are organizing ourselves in order to make our position known and to make the people who are in positions of responsibility accountable.’

“To say there was no role for protests would be partly like saying that the First Amendment isn’t doing us any good. It can be a vehicle for people to express themselves to the institutions of power. I think that the populist upsurge that we see in the Donald Trump phenomenon is a kind of protest. It’s a kind of way that people without voices are trying to get their voices heard, and I wouldn’t be against that categorically.”

One of Loury’s most controversial views is his opposition to affirmative action. Though he has been the beneficiary of affirmative action programs and believes they have been useful tools in the past, he believes that these programs make the recipients doubt their own worth.

“In the fall of 1970, I was enrolled as an undergraduate with a full scholarship at Northwestern and, of course, that was affirmative action. I probably could have been admitted to MIT [for a PhD] even without a special program because my record was just that stellar. I was taking PhD-level courses as a senior at Northwestern in mathematics and in economics, and I was doing very well in those classes. I was an outstanding prospect regardless of my race, but there’s no way that I can ever know whether or not my admission to Northwestern would have happened even if I hadn’t been Black. Just like there’s no way for me to deny that my appointment as a tenured professor of economics at Harvard in 1982 — just 10 years after I graduated from Northwestern, and only six years after I completed my PhD — full professor, the first Black to have that position in economics at Harvard.

“Well, OK, they brought me in as a joint appointment in economics and Afro-American studies. They wanted to beef up their Black Studies Group. If I weren’t an African American working to some degree on those issues, I’m quite sure that I would not have been offered that position. I had difficulty dealing with the pressures of that position in part because I wasn’t sure that I was ‘good enough’ to pull it off. I was afraid that I was going to fail, and that paralyzed me and I ended up changing the direction of my career in part because of that.

“I think as a historical matter, there was a necessity for something like affirmative action coming out of the period of the Second Reconstruction, out of the post-1960s civil rights environment. But that was 60 years ago. It’s not something that we want to be doing in the second third of the 21st century.”

If systemic approaches like reparations and affirmative action aren’t the right way to go, what is?

“The messages that I would put out within the community’s larger cultural matrix — church basements, popular culture, and things like that — I would want to see be more a message of responsibility and development. Biden goes to Morehouse College and gives a commencement address, and he reminds the students there that this is still America where racism can rear its ugly head at any moment. And he basically says, ‘Support me and I’ll protect you from the racists,’ when what might have been said is ‘You stand on the threshold of greatness. This is an open society. Anything is possible here, hit the ground running, go forth, there are Black billionaires, start a business, etc.’ Affirmative to the possibilities of what can be done in this country and accepting our responsibility to seize the reins of opportunity and to make something of our lives.

“Another thing that I would want to see is transracial politics. I don’t like the reparations stuff. I don’t want to parse the country up into racial enclaves and then get into a quid pro quo negotiation of who’s going to do what for whom. I’d much rather see a transracial, or, if you like, class-based [approach]. So if I take the schools [that] are not working: That’s a problem for everybody. It’s not just a problem for Blacks. If I think that the police are disrespectful, that’s a problem for everybody. It’s not just a problem for Blacks. What about inflation? What about taxes being too high? What about what are we going to do about the climate? These are not racial issues.

“A transracial politics for the larger public space, and an empowerment and seizing opportunity and accepting personal responsibility for the more communal space, is the way I think about it.”

Carine Hajjar is a Globe Opinion columnist. She can be reached at carine.hajjar@globe.com.