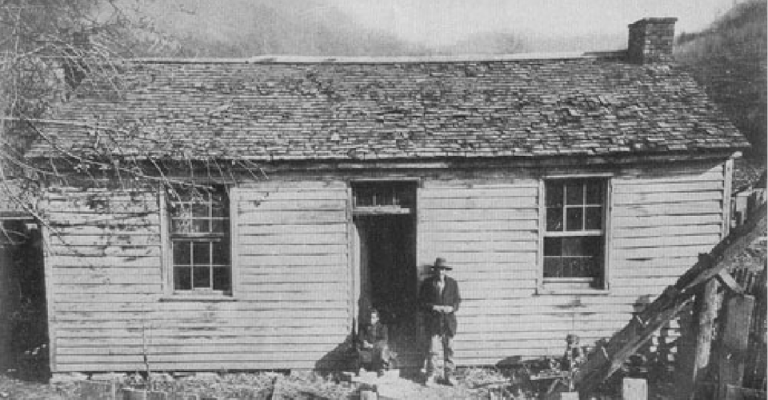

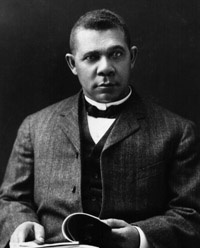

Last week I mentioned in two posts (here and here) the revived “artisanal salt” industry that a brother and sister, Lewis Payne and Nancy Bruns, are creating on the site of the family’s very successful 19th-century salt factory in the little town of Malden, West Virginia. Malden, just outside Charleston, was previously known as Kanawha Salines, after its dominant industry. Its greatest source of fame, apart from though related to the salt works, is as the boyhood home of Booker T. Washington. (More current source of fame: the football phenom Randy Moss grew up in an adjoining hamlet.)

Washington’s family, who were slaves, had left a farm in Franklin County, Virginia, when they were freed by the arrival of Union troops in the spring of 1865. (I am drawing from an official narrative by Louis R. Harlan for the West Virginia Division of Culture and History.) They made their way to the Kanawha valley of the relatively new state of West Virginia, and there the 9-year-old Booker was soon put to work in the salt furnaces, where brine was boiled down to make commercial salt. From the state narrative:

Quite early one morning, Booker learned one of the reasons his stepfather had sent for him to come to Malden. He was routed from bed and he and his brother John went to work helping Wash Ferguson [his stepfather] pack the salt.

After the salt brine had been boiled to a damp solid state and dried in the “grainer” pan, it was necessary not only to shovel the crystallized salt into the barrel but to pound it until the barrel reached the required weight. The boys’ work was to assist their stepfather in the heavy and unskilled labor of packing. Their workday often began as early as four o’clock in the morning and continued until dark, and the stepfather pocketed their pay.

Perhaps he was too poor to behave otherwise, and the exploitation of children by their parents was widespread in the nineteenth century in agriculture, textile mills, mining, and all low-wage industries. Nevertheless, the boys deeply resented Wash Ferguson for his greed and shortsightedness. They turned away from him, and he never became father to them in the sense of a model for their behavior or a person on whom to rely…

The first thing Booker learned to read was a number. Every salt packer was assigned a number to mark his barrels, and Wash Ferguson’s was 18. At the close of every day the foreman would come around and mark that number on all of the barrels that Wash and his boys had packed, and the boy Booker not only learned to recognize that figure but to make it with his finger in the dust or with a stick in the dirt. He knew no other numbers, but this was the beginning of his burning desire to learn to read and write.

University)

You can read much more at the official site, including the ups and downs of the salt industry in this part of the world in the years leading to the Civil War and thereafter, and of course from Washington’s autobiography. In fact, here’s part of what he says himself about the salt-works years:

My step-father seemed to be over careful that I should continue my work in the salt furnace until nine o’clock each day. This practice made me late at school, and often caused me to miss my lessons.

To overcome this I resorted to a practice of which I am not now very proud, and it is one of the few things I did as a child of which I am now ashamed. There was a large clock in the salt furnace that kept the time for hundreds of workmen connected with the salt furnace and coal mine. But, as I found myself continually late at school, and after missing some of my lessons, I yielded to the temptation to move forward the hands on the dial of the clock so as to give enough time to permit me to get to school in time. This went on for several days, until the manager found the time so unreliable that the clock was locked up in a case.

A reader in the Charleston area, Cyrus Forman, criticizes me for not including more of this slavery-and-afterwards background in my two first reports. He writes:

[Various complimentary comments about China coverage, where the reader has also lived and worked] but I just wanted to write about what I regard as a pretty serious omission to your recent article.

I’m a native of Charleston, West Virginia, and grew up in a neighborhood that was about ten minutes from the Dickinson property. I wrote my masters thesis on the history of the Kanawha salt industry, and my thesis focused on the one aspect of that industry’s history that is absent from your article: the role of slavery in the West Virginia salt industry.

During its heyday the vast majority of salt mine workers were enslaved people of African descent, leased by salt companies who could not find free labor that was willing to endure the brutal conditions of this workplace. The salt mines were incapable of operation without a legal, political, and economic structure that made massive human trafficking a regular feature of the antebellum Virginian economy and understanding the specifics of this wretched trade are central to understanding the early history of my hometown.

It is worth noting that I personally grew up knowing vaguely that our chemical industry had origins in the production of some sort of red-tinged salt, but it was not until I had been working as a historical educator on American slavery for 6 years that I discovered the role slavery played in the place I grew up.

I have nothing against the Dickinson’s business, in fact, I am a big fan of any industry that might improve the poor image that the public has of West Virginia, but I think it is a bad idea to write an article about this topic and touch upon the history of this industry without a single mention of the role slavery played in building this industry.

It is not fair to the men who were forced to work in this industry to celebrate the salt without celebrating them as well.

Noted. This was a story about entrepreneurs in a depressed area of the country in 2014, but even in the “new” country of America everything has a past, and this part of the salt industry’s origin-story does deserve mention.