BEETOWN TOWNSHIP, Wis. — Names engraved on the stones in a small cemetery on a windy ridgetop in southwest Wisconsin hint at a history hidden by the passage of time.

“Thomas Greene April 10 1843 – Co. F. U.S. Colored Heavy Artillery.”

Another weathered stone bears this name and dates:

“Edward Shepard 1850-1946.”

Barely legible engraved words provide a kind of census:

“Queen Richmond. D. Dec. 31, 1893. Aged 85 years.”

The cemetery in Section 11 of Beetown Township in Grant County bears the name of the community it served: Pleasant Ridge.

Located on the north side of Slabtown Road, about five miles southwest of Lancaster, the cemetery is the only remaining reminder of a once-thriving community founded by freed Black slaves and eventually boasting a church, a community hall and an integrated school.

“It was one of the first Black communities in the region, and I don’t think a lot of people recognize it or know about it. These folks had a thriving, tight-knit farming community,” said Winifred Redfearn, a history lecturer at University of Wisconsin-Platteville who has researched Pleasant Ridge. “There’s this idea of things that are hidden in plain sight. Pleasant Ridge is like that. There’s not much left to it.”

Estimates of the peak population of Pleasant Ridge vary but probably settled at 100 or slightly higher.

Pleasant Ridge was a dot on a map, but it was a dot rich in significance — a community that by its existence upends many modern misconceptions about rural life in the early decades of the tri-state area.

“The representation in the Midwest was a lot more diverse than a lot of people might think,” Eugene Tesdahl said.

Tesdahl, an associate professor of history at UW-Platteville, has extensively studied Pleasant Ridge and the community’s founding in 1850, rise in the late 19th century and eventual decline by the beginning of World War II.

Tesdahl said it is imperative that the community’s story continues to be explored and told.

“Black history is human history, and human history in the United States is American history,” Tesdahl said. “The history of Pleasant Ridge, Wis., is important every day of the year and every month of the year — not just in Black History Month (in February). It tells us a much more complicated story about this early period of the tri-state region.”

Anthony Allen, president of the Dubuque branch of the NAACP, described the story of Pleasant Ridge as one of a Black community’s advancement cut short by pervasive conditions in the early 20th century — part of a history that he sees fading from modern consciousness.

“History is not respected anymore in education,” Allen said. “We are lacking in educational depth, and we need to get back into it.”

‘A NEW LIFE’

A legal document housed at the Grant County Historical Society’s museum in Lancaster is dated Sept. 25, 1849, and was signed by a justice of the peace for Fauquier County, Va.

Drawn up in pursuance of Virginia law, the document states that “Charles Shepard, a dark mulatto man, having two small scars just above the left eye,” who was about 25 years old and stood 5 feet, 8.5 inches, had been emancipated by the will of his deceased owner.

The deceased owner’s name was Sarah Edmonds, according to records from the Wisconsin Historical Society.

Newly freed, Shepard became the catalyst for the story of Pleasant Ridge.

“Charles and his wife, Caroline Shepard, had left Virginia, and they came to Grant County, Wis., to Lancaster,” Tesdahl said.

Tesdahl said Caroline Shepard had been born free.

“She married Charles Shepard, he then got his freedom, and they came to strike out on a new life in Wisconsin,” Tesdahl said.

Grant County Historical Society records indicate the Shepards traveled to Wisconsin with a relative of Charles’ former enslaver named William Horner. Tesdahl said the reasons for the three people coming west to Wisconsin is not clear.

“It is hard to say if there was coercion or incentive for them to come with him,” Tesdahl said. “Either or both could be possible.”

Horner originally had hoped to make money in southwest Wisconsin’s lead mining industry, according to historical society records. Instead, the newcomers turned to agriculture.

“When they got here, they were skilled in agriculture,” Tesdahl said. “They acquired land southwest of Lancaster in Beetown Township.”

Historical society records indicate Charles Shepard and his brother, Isaac Shepard, saved money and purchased 200 acres and their own homesteads. They called their hillside homes “Pleasant Ridge.”

Soon, they would be joined by others seeking freedom.

‘IT GREW INTO … A VILLAGE’

Black residents were not unique to the region that would become the tri-state area.

Tesdahl’s research indicates that nearly 100 Black people worked in the lead mines and smelters of southwest Wisconsin or in houses associated with miners. Between 1826 and 1842, many of these individuals were enslaved in a territory where slavery was illegal.

“Black Americans were some of the first people in Galena, Ill.; Dubuque, Iowa; Prairie du Chien, Wis.; Mineral Point, Wis.; Platteville, Wis.; Potosi, Wis.; and Cassville, Wis.,” Tesdahl said. “Black people were some of the first non-Native people in those communities.”

Tesdahl said many of the fledgling communities of what would become the tri-state area were founded around 1827.

“Not only were there enslaved Blacks in many of those communities in the 1820s, 1830s and 1840s, but there were freed Blacks,” Tesdahl said.

Redfearn, the history lecturer, said the evidence of local, illegal slavery is a surprising facet of local history.

“I’m from the region — I grew up in Hazel Green — and one of the individuals I have studied is Paul Jones, who was formerly enslaved at Sinsinawa (Wis.),” Redfearn said. “I never knew about that growing up in Hazel Green. It wasn’t taught to us in school.”

After its founding, Pleasant Ridge offered a place of freedom for Black residents.

“None of the folks at Pleasant Ridge were enslaved while they were at Pleasant Ridge,” Tesdahl said. “It was a free Black farming community.”

Tesdahl said various Black people associated with the lead mining industry of the 1830s-1840s in what was then the Territory of Wisconsin eventually would find their way to Pleasant Ridge.

“Some of the earlier research I had done on enslaved Black lead miners in Wisconsin intersects with the history of Pleasant Ridge,” he said.

Tesdahl said a woman enslaved in Potosi, Wis., during Wisconsin’s territorial era, America Jenkins, eventually would figure into the Pleasant Ridge story.

“America Jenkins later became a free woman and worked as a nanny in Lancaster in the 1850s,” Tesdahl said. “By the time she stopped working, she moved to Pleasant Ridge and was a respected matriarch of the community.”

Pleasant Ridge also began to draw former slaves and free Black people from other states, including Tennessee, Missouri and Arkansas, according to Grant County Historical Society records.

“Within about 20 years, several more free Black families — most of them formerly enslaved — joined (the Shepards) there (in Pleasant Ridge),” Tesdahl said. “It grew into what we might call a village today.”

A little more than a decade after its founding, Pleasant Ridge began a tradition that would contribute to American history on a broader scale.

“Members of the Shepard family served in segregated units in the Civil War, in the Union Army,” Tesdahl said. “There was a tradition of military service in Pleasant Ridge dating to the Civil War.”

Wisconsin Historical Society records indicate that when a restriction on Black soldiers was lifted in 1863, Charles Shepard and his son, John, both walked to Prairie du Chien, Wis., to enlist in the Union Army. Charles Shepard served with the segregated 50th U.S. Infantry Regiment and died at Vicksburg, Miss. John Shepard was a private in the segregated Company K, 42nd Regiment. He died of disease at the end of the war in Cairo, Ill., as he attempted to return home to Pleasant Ridge.

At least eight other Black veterans returned to Pleasant Ridge after the war to operate farms, according to the state historical society.

The returning veterans and their families began to grow, and the community developed with that growth.

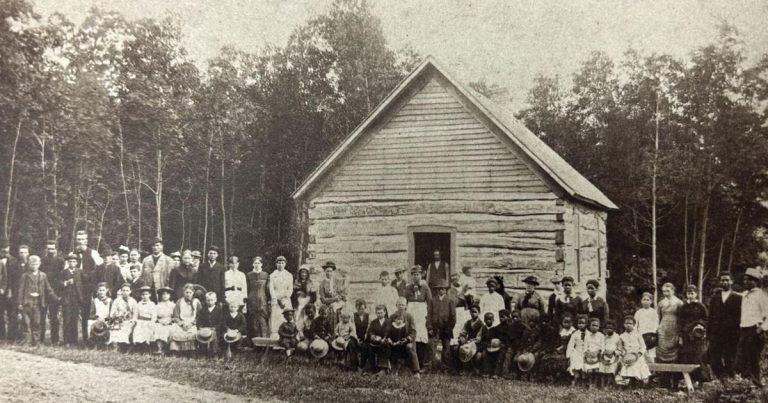

“By the 1870s, Pleasant Ridge had a Free Methodist Church, and by the 1890s it had a school,” Tesdahl said. “That was an integrated school. Some sources suggest that it was one of the first integrated schools east of the Mississippi River. That fact is debatable, but it was an integrated school, so Black and White students attended.”

The state historical society refers to the school, District School No. 5, as “one of the first integrated schools in the nation.”

A STORY OF SUCCESS

Pleasant Ridge residents established a cemetery in 1883, and a visitor walking among its grave makers will read names that personify the history of the community.

“Key families include the Shepard family, who founded Pleasant Ridge,” Tesdahl said. “By the 1880s, the Greene family came after getting their freedom in Missouri. It is hard to say how they heard of Pleasant Ridge, but they became another prominent family.”

Over time, the “e” would drop from the end of the Green family name. In 1938, Green family patriarch Tom Green told a Platteville newspaper about his experiences as a slave in Missouri.

“I saw too many families broken up on the auction block,” Tom Green said in 1938. “A good strong man or a good (woman) would bring $1,000 each, while (slave) owners would often give away a mammy’s children to get rid of them.”

Tesdahl said that by the 1880s there were at least 10 freed Black families living in Pleasant Ridge.

Tesdahl said several members of the Pleasant Ridge community left southwest Wisconsin for higher educational studies at historically Black colleges and universities.

One such resident was Dr. Howard Shepard.

“He went to Fisk University in Tennessee and became a dentist,” Tesdahl said. “We see that part of the story of Pleasant Ridge is a story of success for many of these Black families. We see resilience.”

Tesdahl likens the story of Pleasant Ridge to another rural Black community in the Midwest — New Philadelphia, Ill.

“Like Pleasant Ridge, New Philadelphia was founded by free Blacks in Illinois and was a farming community,” Tesdahl said. “They had other businesses, including several shoemakers, which shows that the rural Midwest was not only much more diverse (than some people might think), but Black businesses were thriving.”

Located in Pike County in western Illinois, the now-vanished community of New Philadelphia was the first town planned and legally registered by a Black American, formerly enslaved Frank McWorter, prior to the Civil War, according to the National Park Service. The New Philadelphia National Historic Site was established as a national park in December 2022.

New Philadelphia eventually began to decline, and by the 1940s there were no structures standing to provide testament to its existence.

A similar fate was in store for Pleasant Ridge.

A STORY OF DECLINE

Black residents of Pleasant Ridge owned about 700 acres of farmland in 1895, according to the Wisconsin Historical Society. Women in the community formed a group called the Autumn Leaf Society in 1906. The group organized dances, dinners and an annual reunion barbecue.

By the early years of the 20th century, however, Pleasant Ridge already had begun its decline.

Tesdahl said Pleasant Ridge, New Philadelphia and many other rural Black farming communities declined between the end of World War I and the beginning of World War II.

“I and some other scholars have started to work on how and why Pleasant Ridge ceased to be a Black rural community,” he said. “A quick answer is it was due to both push and pull factors.”

Black residents of Pleasant Ridge continued the community’s military tradition in World War I.

“Some of the youth, including members of both the Green and Shepard families, joined the U.S. Army and were put in segregated units,” he said.

These soldiers’ post-war experiences contributed to the decline of their community.

“Like a lot of White servicemen, Black servicemen returned from World War I and did not get the bonuses they were promised,” Tesdahl said. “This caused terrible economic stress. Also, Black servicemen were promised that if they served, racial segregation would decrease and economic opportunities for Blacks would increase. Neither of those were true. In 1919, there were acts of racial violence across the country.”

This violence extended into the 1920s and beyond.

“At that point of time, African American communities were being destroyed by hate,” Allen said.

Tesdahl said the emptying of rural Black farming communities in the Midwest in the early 20th century partially coincides with the Great Migration — “this large movement of Black families from the Deep South, states like Mississippi, to get away from increasing racial violence like the growth of the Ku Klux Klan in the late 19th century.”

Tesdahl and Allen both note that local chapters of the Ku Klux Klan existed in Illinois, Wisconsin and Iowa during this period.

“The KKK was instrumental in destroying African American communities,” Allen said. “It happened all over the country. In 1925, there was a large Klan rally in Dubuque.”

The push factor of violence against Black Americans coincided with the pull factor of greater opportunities elsewhere.

“There were doors opened to education and employment opportunities (for Black Americans) in larger areas, despite segregation,” Tesdahl said.

Wisconsin Historical Society records indicate that the youth of Pleasant Ridge faced limited economic and marriage opportunities due in part to the community’s small size and relative rural isolation.

Grant County Historical Society records indicate that as decades passed, the youth of Pleasant Ridge would travel far afield for greater economic opportunities — some taking up residence in Washington, DC.

Among the residents who remained in Pleasant Ridge would be the woman who helped keep the community’s memory alive.

‘SHE’S A SIGNIFICANT AMERICAN’

“Olive Shepard Green, she went by ‘Ollie,’ was the last descendant of the Pleasant Ridge community to live at Pleasant Ridge,” Tesdahl said. “She was born there in the late 19th century, and she would pass away there in 1959.”

Green went by “Mrs. Dick Lewis,” her husband’s name, when she was interviewed by the Telegraph Herald for a story that published on June 1, 1958.

The story traces Green’s family history to 1863 Missouri, when her grandfather and other family members boarded a train at St. Charles, Mo., and rode it to Dunleith, Ill. — later known as East Dubuque.

“I still have the trunk that grandfather Green brought with him on that trip,” Green told the TH in 1958. “Years later, I was told that by the time they had reached East Dubuque, the clothes were stolen, leaving just an empty trunk to be toted first to Potosi, then to Pleasant Ridge.”

Green told the TH she remembered relations between the Black residents of Pleasant Ridge and their White neighbors as being friendly.

“You hear so much about racial troubles in the papers today that you begin to realize how lucky we were here,” she said in 1958. “When we were kids, we really never realized any difference in color. I remember when our White neighbors would ask my father to help stack the hay. He knew just how to do it.”

The 1958 TH article notes that Green was the only representative of what had been a thriving community. All that was left, the story said, was “an outcropping of tombstones amid the wild Indian tobacco flowers in the tiny Pleasant Ridge Cemetery.”

Green’s words in 1958 helped perpetuate the story of Pleasant Ridge. Tesdahl said her actions in the 1950s were even more significant in safeguarding the community’s tale.

“She is a big reason why a lot of the artifacts and the documents of the (Greene/Green) family, dating back to 1848, are at the Grant County Historical Society,” he said. “This is a world-class collection of artifacts and documents, and it is there because of her stewardship.”

Tesdahl said Green joined the historical society in 1950s and served on its board of directors — an audacious move at the time.

“To be a Black woman on any board in the 1950s — especially in the rural Midwest — was rather unique. It was gutsy because it could have been dangerous for her,” Tesdahl said.

Green donated boxes full of documents, photographs and other artifacts related to Pleasant Ridge to the historical society. Inside the boxes is evidence that helps bring the community’s story out of hiding.

“It seems like an act to ensure that Black history and her family history would be preserved,” Tesdahl said. “Because of that, I think she’s a significant American.”

Tesdahl said Green’s curating of the history of a now-vanished community provides evidence that the tri-state area developed in diversity.

“Modern people living in the tri-state area should care about Pleasant Ridge because there was a Pleasant Ridge — there is early Black history here,” Tesdahl said.

Redfearn said the individuals who combined to create a Black community made contributions to the area that should reverberate through the decades.

“It can be problematic if we don’t remember or care about communities like (Pleasant Ridge) because if we’re not caring about diverse histories, we’re not getting (the full picture),” Redfearn said.