Celebrating Black History Month in Louisville, Kentucky, SoIN

These 28 stories explore the rich history of African Americans and their impact throughout Kentuckiana.

LOUISVILLE, Ky. — During Black History Month, WHAS11 News shared ‘Moments That Matter’ – stories of African Americans and their impact on our communities in Kentucky and southern Indiana.

The Kentucky Center for African American Heritage celebrated 10 years in the Russell neighborhood in 2019. The mission of the center goes back to the late 1800s and the plans for the future include sharing the rich history of Black Louisville and Kentuckians. Click here for the story.

Following the death of Breonna Taylor in March 2020, many in the Louisville area took their fight for justice to the streets — marching, chanting and protesting. As demonstrations continued, new community leaders and diverse voices emerged. One of those voices belongs to Carmen M. Jones. When the protests began, Jones’ leadership emerged and she became a mother in the streets. Click here for the story.

Louisville men’s basketball trailblazer Wade Houston grew up in Alcoa, Tenn., a small town about 20 minutes outside of Knoxville. Houston, along with Eddie Whitehead and Sam Smith, became the first Black basketball players to sign with the University of Louisville.

What followed was a Cardinal career that helped lay the foundation for Louisville basketball. Houston was a part of two teams that made the postseason after moving up to the varsity squad in the 1963-1964 season.

Houston had always been inspired to teach and coach from observing as a student-teacher. He led Ahrens and Male High Schools, winning a state title at the latter. But he was becoming frustrated with the salary and busing plan implemented in Louisville at the time, so he decided to follow a different path. Read more of his story here.

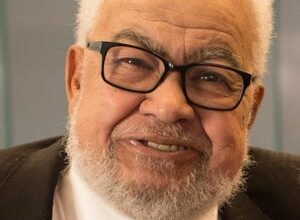

Reverend Louis Coleman used his faith and his love for the community to pursue his commitment to making the streets safer. Armed with his bullhorn, he led and participated in social justice protests in the streets of Louisville and beyond. While he accomplished many things during his life, his legacy isn’t measured by accolades. Rather, Coleman’s influence is better reflected in the many people he mentored publicly and privately every day. Click here for the story.

Louisville detective and Civil Rights activist Shelby Lanier Jr. is an icon to the city of Louisville, an unwavering voice for justice and a lover of people. Lanier filed a lawsuit against the Louisville Police Department, while he was an officer, accusing them of discrimination against candidates and officers. Lanier’s landmark lawsuit pushed LMPD to be more inclusive and helped Black citizens secure spots on the force. Click here for the story.

With the passage of the Day Law, doors were closed to Blacks at Kentucky’s Berea College. On October 1, 1912, those students were welcomed inside the Lincoln Institute of Kentucky. The Lincoln Institute was soon recognized as one of the premier schools for African Americans, teaching students both academic and life skills. Click here for the story.

Segregation and racism early on in American history led to the establishment of Black institutions—one being Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs). There are two in Kentucky – Simmons College of Kentucky and Kentucky State University. These schools provide a nurturing, welcoming and educational environment for everyone who attends. Click here for the story.

‘Separate but Equal’ was the concept behind the Day Law in Kentucky. The bill prohibited Blacks and whites from attending the same school until the mid 20th century. The same school could not operate separate Black branches within 25 miles of each other, either. The Day Law was active until 1954. Click here for the story.

The year was 1922. America was still segregated and women had only been given the right to vote two years prior. But a woman named Bertha Whedbee would step into a role that would symbolize progress for both women and the Black community throughout Louisville. Click here for the story.

The “Louisville Defender” was one of three local newspapers that covered stories directly affecting the African American community in the early to mid-1900s – and it’s still covering these stories today. Click here for the story.

On Louisville’s South 13th Street stands an old brick building – like so many other brick buildings from a century ago. This one has a large “Eight” carved in stone at the top. Many may drive right past it without knowing its history, but the building was the very first firehouse in Louisville to house African American firefighters. Click here for the story.

For more than 100 years, Black Greek fraternity members have been leaders in Louisville and Southern Indiana. They provide backpacks for schools, give out Thanksgiving and Christmas baskets, help organize blood drives, participate in cancer awareness, help people register to vote and mentor young men and women. Click here for the story.

Nate Northington grew up in Louisville’s Newburg neighborhood and went on to make history as one of the first Black football players at the University of Kentucky. His desire to bring change helped break the color barrier in the SEC. His legacy can still be seen today outside of Kroger Field. For more on this story, click here.

One of the things Kentucky is most famous for is the billion-dollar bourbon industry, but we don’t always hear about African Americans’ contributions. A Kentucky history professor, the Evan Williams Bourbon Experience, and the Frazier History Museum are all highlighting the Black heritage and legacy in the bourbon industry. For more on this story, click here.

It’s one of the city’s forgotten towns – Little Africa. The town was set near what the community now knows as the Park DuValle neighborhood. It’s where freedmen and women settled after the Civil War and the Emancipation Proclamation. It was described as a shantytown where many made do with what resources they had and eventually turning it into a thriving community by the 1920s. For more on this story, click here.

The two schools played a vital role in educating Black Kentuckians during segregation. Central High was the most progressive high school in the state while the Lincoln Institute specialized in training educators and offered vocational education programs. For more on this story, click here.

Stanley Madison founded the Lyles Station Historic Preservation Corporation in 1998 to shares the community’s forgotten history. It’s a small community in Gibson County, Ind. and it’s one of the last remaining settlements where African American farmers were responsible for producing a huge portion of food in the Midwest.

Just a mile from downtown Louisville is the Smoketown neighborhood. It was named for its large smoke-producing kilns in the area. In the 1850s, residents were of German descent but changed due to the arrival of thousands of freed slaves.

Black Greek sororities have been around since the early 1900s. Members of Alpha Kappa Alpha, Delta Sigma Theta, Zeta Phi Beta and Sigma Gamma Rho are dedicated to their sororities for life; service does not end when they graduate college. Click here for the story.

In west Louisville lies nearly 100 years of sanctuary for Black residents. Chickasaw Park’s historical significance stretches far past its illustrious, 61-acre landscape.

Berrytown, located in eastern Jefferson County, began in 1874 by former slave Alfred Berry. He carved out a life for his family and other African-American landowners in the new community,

Wes Unseld was not the first Black player to suit up for Louisville men’s basketball. But the Naismith Basketball Hall of Famer, who died at the age of 74 back in June, was the one who changed the Cardinal program. His friends and former teammates remember him as a gentle giant blessed with sheer strength. Click here for the story.

The influential Kentuckian was one of the members of the “big six” civil rights leadership team and even had a prominent role during the 1963 March on Washington. The Lincoln Institute remembers Young’s legacy and impact on social justice. Click here for the story.

The travel bible for African Americans who looked for safe spaces during the segregation and the Jim Crow era. The original Green Book was published from 1936 to 1966 and created by Victor Hugo Green.

Theo Edwards Butler is revamping it to a modern-day database of Black businesses not only to showcase them but uplift as well. Click here for the story.

In January 1856 Margaret Garner, a slave in Boone County, Kentucky made a dramatic escape to freedom to Ohio. Her husband and four children were with her. Her story was the basis for Toni Morrison’s book ‘Beloved.’

When the Western Library opened in 1905, it was the first library in the U.S. exclusively for African Americans, staffed by African Americans. It gave children in Louisville a chance at a proper education, something their parents and grandparents didn’t have. Nearly a century later, donations from the community and Prince kept it open. Click here for the story.

Soul musician Wilson Pickett, known for hits like “Land of 1000 Dances”, “Mustang Sally” and “In the Midnight Hour,” has been gone for 15 years – but his family still calls Louisville home after more than four decades. His sister Emily “Jeannie” Rochelle recalled Pickett as independent and destined for stardom. Chick here for the story.

She’s known for her beautiful works of art, but Elmer Lucille Allen’s knowledge runs deeper. She was the first African American chemist at Brown Forman and, at 89, has experienced a lot in her lifetime. Her artwork is on display right now. Click here for the story.

Since 1969, the Carl Braden Memorial Center has hosted meetings to develop plans to dismantle systemic racism. A white couple, Carl and Anne Braden, are behind it. Today, many throughout the community use it as a beacon to continue calls for social and racial justice. Click here for the story.

For more than seven decades, Mattie Jones has been a force in the Civil Rights Movement locally. Having faced the harsh realities of racism, Jones became an activist, fighting for the rights of Black Kentuckians and those across the nation. Click here for her story.