A joyful noise: How a long-closed Vermont business continues to resonate today

BRATTLEBORO — The story of Jacob Estey begins like a Charles Dickens’ novel: Born into poverty in 1814, the late New Englander was farmed out as a child laborer at age 4 and ran away at age 13, only to establish a namesake local company that was once the largest organ manufacturer in the world.

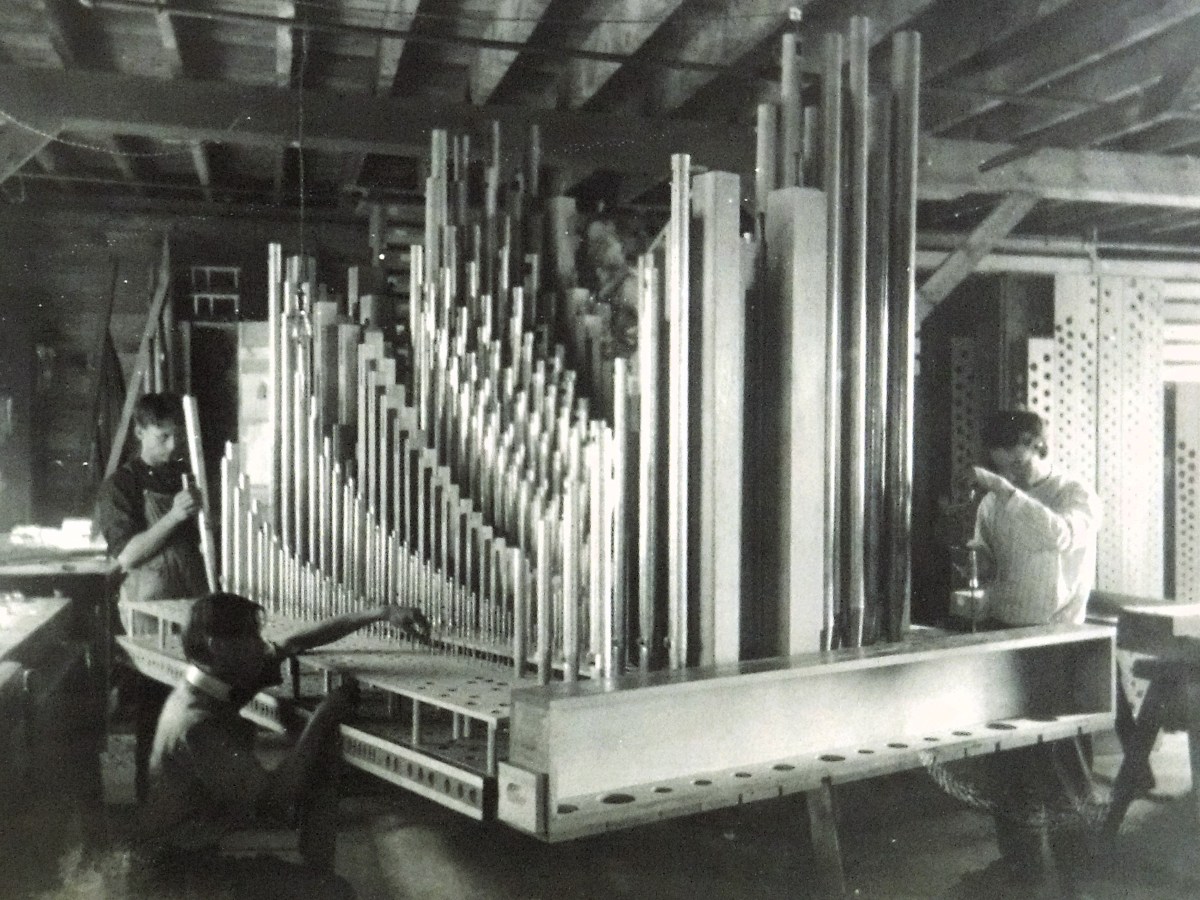

Estey sold pump models to families seeking entertainment in the days before electronics, as well as pipe instruments to such luminaries as automaker Henry Ford, who rolled into Brattleboro in 1915 to see one specially crafted for his Michigan mansion. But soon after finishing its biggest project in 1952 (a $65,000 commission for Florida Agricultural and Mechanical University), the company was sold to a New Jersey firm in 1953 and shuttered in 1960.

End of story? Hardly. Talk to historians and they’ll tell you how the Estey Organ Co. — a pioneer of equal pay for women and higher education for people of color — lives on this holiday season in century-old instruments still making music everywhere from Maine’s South Paris Baptist Church to California’s Universalist Unitarian Church of Santa Paula.

“Half a million organs went all over the world,” Barbara George, a volunteer leader of Brattleboro’s Estey Organ Museum, said in a recent interview. “People still get in touch with us from as far away as Australia.”

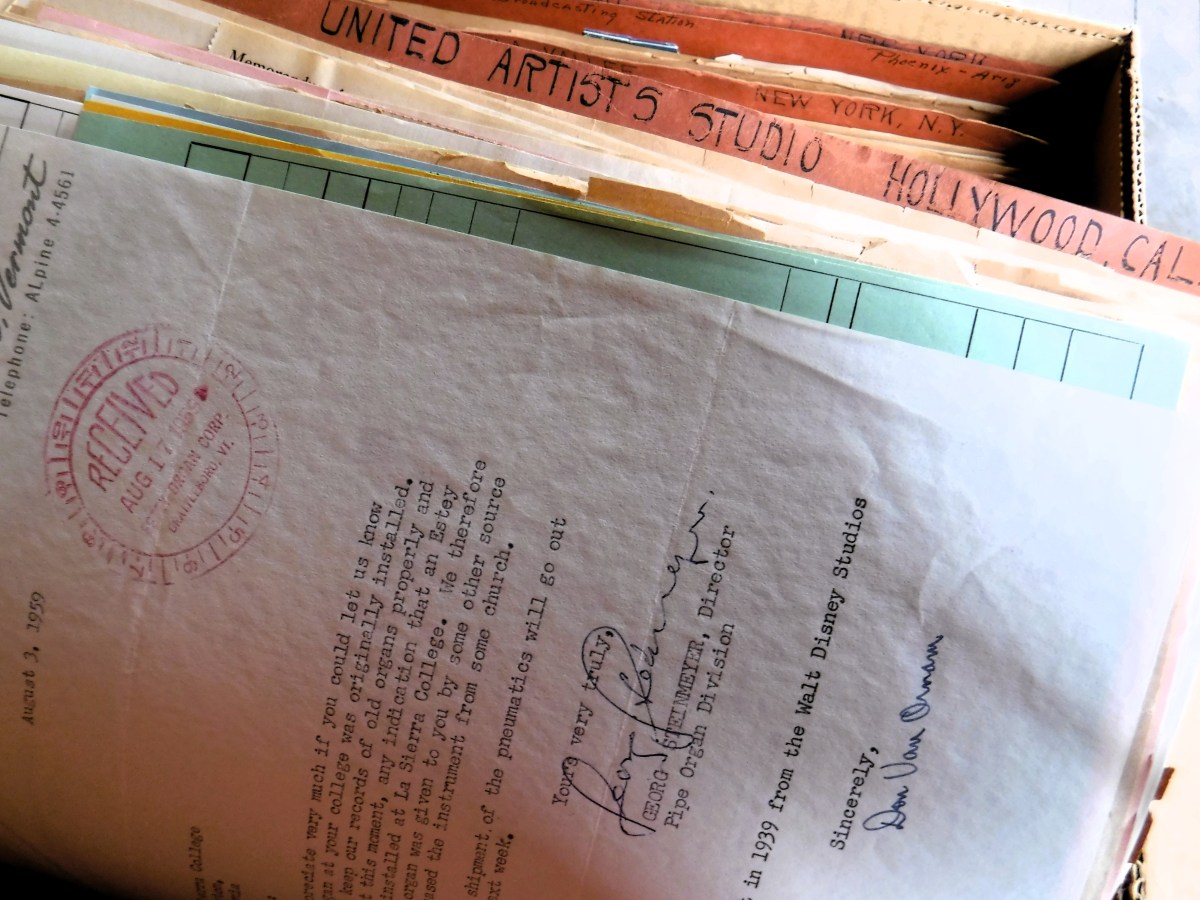

The long-closed manufacturer also resonates through its records. Estey sold 500,000 smaller reed organs for homes and churches from its founder’s start in 1852 to the factory’s finish 108 years later. It additionally fashioned 3,261 larger pipe instruments for bigger public buildings, documenting the latter in folders containing everything from an initial letter of interest to a final shipping order.

That paperwork, filling more than 150 boxes, sat for years in the attic of one of seven slate-shingled factory buildings that still stand on Brattleboro’s Birge Street. Then the head of the national Organ Historical Society discovered the dusty collection during a recent visit to Vermont.

“Oh, my gosh, this is a treasure trove!” W. Edward McCall recalled telling his hosts.

And so Organ Historical Society archivists have moved the material to their repository outside Philadelphia, where they’re set to sort and scan everything for public online research.

“It’s a lot of work,” McCall said of the effort. “But the Estey Organ Co. was really well regarded and had quite a following. You can see by the amount of material the depth of its success.”

Jacob Estey didn’t foresee such acclaim when he became a plumber’s apprentice at age 17 and moved on to sell lumber, slate and marble before trying his hand at melodeons at age 38.

“Estey confessed quite readily that he didn’t have a lot of talent for music,” Dennis Waring, author of the book “Manufacturing the Muse: Estey Organs and Consumer Culture in Victorian America,” said in a recent Brattleboro lecture. “But he saw that music was set to become an important part of American expression.”

Soon after the start of the Civil War, Estey branched out into organs for homes and churches, all while bucking tradition by paying men and women the same wage and underwriting a building at North Carolina’s Shaw University that was the first in the nation dedicated to higher education for Black women.

Tapping such advances as the steam engine and telegraph, the company shipped product to every continent except Antarctica, promoting its reach “from the far-off pines of Siberia to the golden shores of the Pacific.”

Estey’s factory would manufacture 200,000 pump organs before his death in 1890, then expand into larger pipe instruments at the turn of the 20th century and portable models used by U.S. Army chaplains during World War II.

The arrival of the television age upended everything. The company hoped to compete by introducing its first electronic organ in 1954, only to fall by the cultural wayside and fold its Brattleboro operations in 1960.

“Barely surviving the jazz age, the domestic organ was not to endure the onslaught of new music and contiguous technologies, especially rhythm and blues and its offspring, rock ’n’ roll,” Waring writes in his book.

But Estey’s closing hasn’t stopped people from contacting local historians with questions about specific instruments.

“I was wondering if there is any information for Opus 2633 built for St. John’s Catholic Church in Rumford, Maine,” a parishioner recently wrote. “I just became the third organist since 1927 to serve as music director and would like to know more. It’s approaching its 100-year anniversary, and we are looking to restore it to its full potential.”

A Michigan musician sent a similar inquiry about an Estey organ installed in 1909 at St. Paul’s German Evangelical Lutheran Church in Detroit.

“The church has been in many hands since it was built and it currently operates as a recording studio for up-and-coming musical artists,” he reported. “I would like to gather whatever information I can to share with the building owners about the instrument as it’s 113 years old.”

Over the past several decades, Brattleboro Historical Society member John Carnahan researched the records to answer what fellow volunteers estimate were more than 1,000 questions. But when Carnahan retired, his colleagues understood the documents required a more publicly accessible home.

“These need to be in their own place, where people can come and do research,” George said at the Estey Organ Museum, which is only open on Saturdays from May to October.

The Organ Historical Society will provide that opportunity, both in-person and online.

“We’ll organize the papers and write finding aids,” McCall said, “so when someone calls up, we’ll be able to provide that information.”

Brattleboro will continue to remember the company through the museum, a nearby roadside historic site marker and an upcoming “Estey Fest” of public music and education programs next fall.

“What this guy was about, how we did it, and the positive effect that he left for us to enjoy,” Waring concluded in his recent lecture, “is a wonderful story that is not appreciated nearly enough by the town, state, country and larger world.”