After Decades of Silence, the Eastern Shore Begins to Reckon With its Difficult History

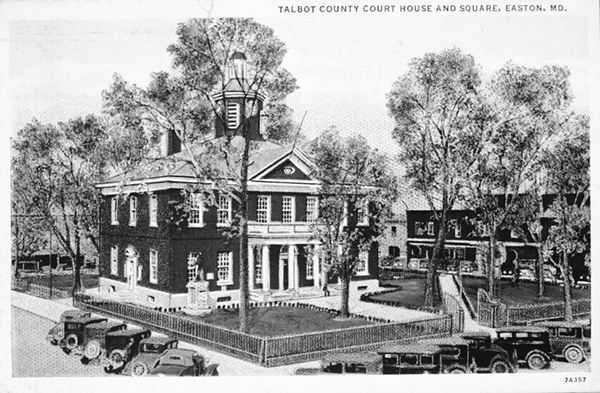

AN ORDINARY WEEKEND in downtown

Easton, the brick sidewalks are mostly empty,

save for the occasional local out for a stroll or a

handful of tourists taking in the iconic Colonial

architecture of Maryland’s Eastern Shore. With

only 16,000 residents, it’s the second-biggest town

on the peninsula, a quaint yet popular stopover

for folks from Baltimore and Washington, D.C., on

their way to Ocean City.

But on a Saturday afternoon this past August,

a commotion could easily be heard from several

blocks away as some hundred people gathered at

the Talbot County Courthouse. Wearing masks and

holding signs, their voices carried as they answered

a call of “Whose courthouse?” with a unified “Our

courthouse!” from a grassy lawn in front of the

looming government building, built in 1794.

Four days earlier, the Talbot County Council had

convened inside the South Wing, sitting along a

dark wooden bench separated by plexiglass dividers

beneath the official seal of “Tempus Praeteritum Et

Futurum,” or “Times, Past and Future,” as they voted

on an issue that had grown increasingly urgent

as months wore on. Earlier in the summer, after a

thousand protestors rallied outside on Washington

Street following the police killing of George Floyd,

calls for Black Lives Matter quickly dovetailed with a

demand to remove the “Talbot Boys.”

The Talbot Boys statue in December 2020.

In front of the courthouse’s grand entrance, the

bronze statue, erected in 1916, depicts a young Confederate

soldier carrying a Confederate battle flag

atop a granite base that bears the names of 96 local

Confederate soldiers and the inscription “1861-1865 C.S.A.,” or Confederate

States of America.

“George Floyd’s death tugged at the conscience of this country,

and people began to connect it to Confederate monuments and

the messages that they send,” says Richard Potter, an Easton native

and head of the local NAACP, who as a boy was mesmerized

by the childlike soldier, sensing he must have done something

special to receive such a significant perch. Only years later would

he become rattled by its history. “The courthouse is meant to be a

place where we can go and get a fair and just trial. And yet to get

inside, Black people have to walk past a monument that says you

belong in bondage.”

This was not the first time that Easton residents had called for

the statue’s removal. In 2015, Potter made the request after a white

supremacist murdered nine people at the Emanuel African Methodist

Episcopal Church in Charleston, South Carolina. Following a closed-door

vote that violated Maryland’s open meetings law, the council

unanimously chose to keep the statue where it stood. Calls came

again after a white nationalist rally in Charlottesville, Virginia, left

one protestor dead in 2017, then again in 2020, when some 700 letters,

including one from this writer, flooded the inboxes of the county

councilmembers, as similar monuments came down all across the

United States.

Protest at the Talbot County Courthouse, Easton, 8/15/2020

It was these events, and further conversations with community

members, that inspired Council President Corey Pack to propose the

removal of the Talbot Boys last summer, even after voting to keep it

in 2015, at the time reasoning that it was history. “A man who fails to

change his mind will never change the world that’s around him,” said Pack, the council’s first and only Black member, as the conversation

grew contentious leading up to the vote that August evening.

Other council members—Chuck Callahan, Frank Divilio, and

Laura Price—expressed opposition to the resolution, pointing to

the COVID-19 pandemic, limited public input, and even the inability

of the deceased Confederate honorees to be present. Price, in a

previous meeting, also resisted the adoption of a diversity statement.

“We have a lot of other problems here—I don’t think that

this is one of them,” she said, referring to county government, but

for many, speaking directly to the larger failure of the town, state,

and country to reckon with its racial past and present.

In the end, the council voted 3-2 to keep the Talbot Boys—believed to be the last Confederate monument, outside battlefields

and cemeteries, on public property in Maryland.

“The removal of this monument would not change the history

of this county,” said councilmember Pete Lesher that

evening. The local historian co-sponsored the resolution

for removal, despite being a descendent of

men listed on the statue’s base. “But the number

who have expressed their feelings on this matter

have made it clear that this is indeed a powerful

symbol, and our actions on it tonight, I’m afraid,

sadly speak of who we are now as a county, and the

extent to which we have not yet changed.”

Within a matter of minutes, a protest emerged

outside of the council’s windows, with demonstrators

chanting, “Take it down,” “Vote them out,” and “Black

Lives Matter,” causing the meeting to end early.