Black entrepreneurs built beach havens in California. Racism shut them down.

Editor’s Note: On September 30, California Governor Gavin Newsom signed a law returning beachfront property to descendents of Willa and Charles Bruce, the Black family who owned Bruce’s Beach, a popular beach resort they built in the early 1900s on Manhattan beach. Like other Black entrepreneurs, their success was stolen through racist land grabs, taken by eminent domain from the city council at the time.

In 1958, Silas White, a Black entrepreneur, set out to transform his dream — opening a Black beach club on the Santa Monica shores — into reality. He would call it the Ebony Beach Club, and he pictured it becoming one of the finest establishments in America for “the accommodation and comfort of my people,” he wrote in a letter to prospective members.

Here, Black members could lounge in luxury in the main entrance’s exquisite bar, be entertained at the jazz stage or take a leisurely dip in a crystal-clear pool. White had plans for exclusive golf tournaments, talent shows and fishing trips, all happening at a unique venue where Black residents could indulge in the “social enjoyment, recreation, and entertainment” that they were denied at “white” beach clubs like Santa Monica’s famous Casa del Mar and Edgewater.

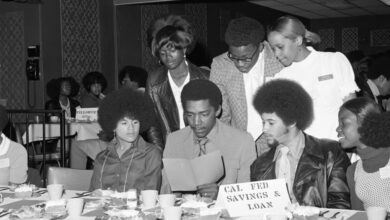

He hoped to become one of the many successful Black-owned businesses in Santa Monica catering to the area’s growing African American community. These pioneers of America’s “frontier of leisure” thrived in Belmar Triangle, the Bay Street Beach and other Californian coastal communities, including “Bruce’s,” a resort owned by African Americans in Manhattan Beach.

For more than 50 years, these spaces served as safe havens for Black Californians seeking refuge from white harassment. They were integral to their communities’ identity and economic growth. But as is often the case in American history, these descendants of formerly enslaved people who moved West in search of a better life were eventually economically sabotaged or driven out. In White’s case, Santa Monica City officials used eminent domain to take his property before his dream could ever be realized.

In recent years, Afro-Angeleno historian Alison Rose Jefferson has sought to resurrect this hidden past through research and projects, working with the city “to reconstruct, represent and reclaim to its rightful place the history of African Americans in California,” she said. In doing so, she aims to celebrate African Americans’ past contributions to Santa Monica while exposing the systemic racism of a society that neglected to document them.

MAIN STREET IN SANTA MONICA, where the first African Americans once settled in shotgun style houses, is now dominated by a row of pearly white buildings: City Hall, the Public Safety Building and the courthouse. It is here that Jefferson’s latest efforts are on display. Sixteen interpretive panels with curated maps retrace Belmar and its surrounding neighborhoods, eventually leading visitors to a permanent exhibit that showcases “the stories of the people, places and events of African Americans who lived in this neighborhood,” Jefferson said. These stories emerged from the research of her book, Living the California Dream: African American Leisure Sites during the Jim Crow Era.

Starting in the early 1900s, during what’s known as the Great Migration, nearly 6 million African Americans left the rural South. Many headed to places like Santa Monica for cheap land, a desirable location and the chance to enjoy the beach lifestyle. “The success of Blacks in Santa Monica made its way back to family and friends,” said Carolyne Edwards, a co-founder of the Quinn Research Center and Archives, who grew up in the beachfront city. That included her own grandfather and uncle, Dr. Alfred T. Quinn, who eventually moved there. “(They saw) property ownership as their means to build intergenerational wealth,” she said, something they couldn’t do back home in Texas, where Jim Crow laws restricted Black families’ ability to purchase homes, or in the many places where the practice of redlining prevented African Americans from obtaining loans to buy property.

Edwards lived two doors down from White, the Ebony Beach entrepreneur, and remembered the excitement that the prospect of his club created within the community. “Everyone was really looking forward to that club opening,” she said.

But the same racist policies that her community had originally fled soon found their way to Santa Monica. Caldwell’s, a popular dance hall frequented by Black Santa Monicans in the 1920s, was closed down after the Santa Monica Bay Protective League —white supremacist suburbanites masquerading as a neighborhood group — lobbied the city to close “nightclubs in residential areas.”

Around that same time, Black investors Charles S. Darden and Norman A. Houston’s Ocean-Front Syndicate resort was targeted by the League, who protested the building permit and successfully derailed the project.

In the following years, white landowners increasingly applied the “Caucasian clause,” which barred Black people from owning or occupying their properties. These racially restrictive covenants mirrored similar policies across the country that prevented African Americans from buying homes or businesses. By 1940, 80% of properties in LA had such language. The Los Angeles Realty Board went as far as barring “all non-white people” from purchasing, owning or residing on a particular piece of property (or land), using language that was included on the property deeds. Soon, this successful Black enclave was also eroded by racism.

The memory of this is one of many reasons Jefferson is determined to preserve the historic and cultural sites of marginalized communities in California. She does her part to reclaim that history through the National Register of Historic Places. She has also created curricula and grade school lessons with the University of California Los Angeles in order to teach some of this storied past in Ethnic Studies classes. The hope is that it will eventually be approved and taught in classrooms to further highlight the voices of people of color in American history.

In the same park as Jefferson’s installation showcasing the history of African Americans in Santa Monica, is a sculpture and time capsule designed by artist April Banks.Inside are students’ re-imaginings of White’s Ebony Beach Club drawings, compiled from a class she taught in January. Banks said she was drawn to highlight White’s work because it asserts a simple but powerful truth: “We as Black people have the right to enjoy recreation in luxury, too.”

Falene Nurse is a freelance writer who’s lived in Los Angeles, New York, London and the Caribbean; she has bylines in Slate, Miami New Times, The Hollywood Reporter and Details.

Note: This story has been updated to include a reference to Alison Rose Jefferson’s book and the location of April Banks’ time capsule.