Black Mountain, NH to Remain Open as Indy Pass, Entabeni Help to Seek New Owner

Black Mountain, New Hampshire will remain open for the 2023-24 ski season, ski area owner John Fichera has confirmed to The Storm Skiing Journal, reversing a decision announced last week on the mountain’s Facebook page.

Driving the reversal is a commitment, from a group led by Indy Pass and Entabeni Systems owner Erik Mogensen, to help Fichera find a new owner for Black Mountain and gather resources for a bridge season.

“We’re not going to open so that John and Jane Fichera can be here for five more years,” Fichera told The Storm. “We’re opening as a transitional year to find a new buyer, a new operator, a new steward for the ski area. And if it’s possible, we’ll have the season to work on it and then finalize the deal sometime next year in the offseason. If it’s not possible, then the writing’s on the wall.”

Leading the search for a new owner will be Andy Shepard, a New England ski luminary who has orchestrated the survival or resurrection of the Saddleback, Big Rock, Quoggy Joe, and Black Mountain of Maine ski areas.

“I’ve always respected and admired the ski community in Jackson,” Shepard told The Storm. “It’s as authentic as you get. It’s a skiing heritage that deserves to be protected, to be cherished and honored. Having been asked to be a part of this project is an enormous honor to me, and I’m very excited about diving in.”

Shepard will work under contract with Indy Pass, which has partnered with Black Mountain since the pass’ inaugural season in 2019-20. Mogensen, who purchased the pass from founder Doug Fish earlier this year, views Indy Pass and Entabeni Systems – which provides software exclusively to small ski areas – as vehicles to help independent mountains compete against the larger ski companies, whose affordable multimountain passes and sophisticated data-analysis machines have rapidly redefined the consumer skiing experience.

“People don’t understand that skiing at a place like Black Mountain is exceptionally fragile until it’s broken,” Mogensen told The Storm. “I have a responsibility as the custodian of the Indy Pass, as a custodian of a large amount of data, to help keep skiing independent.”

While none of this week’s developments guarantee that Black Mountain will operate beyond 2024, the joint efforts of Indy Pass officials, Fichera, and Shepard at least temporarily halt a ski area closure that had blindsided and traumatized New England skiers. They provide a reset and re-evaluation of direction and priorities for the ninth-oldest operating ski area in America, which has spun its lifts for 88 consecutive winters. And they suggest a rough blueprint for how the nation’s hundreds of family-owned ski areas, assisted by Entabeni and Indy, can modernize their business practices to better compete against – and offer a compelling alternative to – the mass-market Epic and Ikon passes.

This is where I would normally drop a paywall. Due to the anticipated impact and reach of this story, I’ve chosen to make this entire issue free. The Storm, however, is a reader-supported publication. Please consider upgrading to a paid subscription to help fund similar future work.

Click here for a mountain stats overview.

Owned by: John and Jane Fichera

Located in: Jackson, New Hampshire

Year founded: 1935

Pass access:

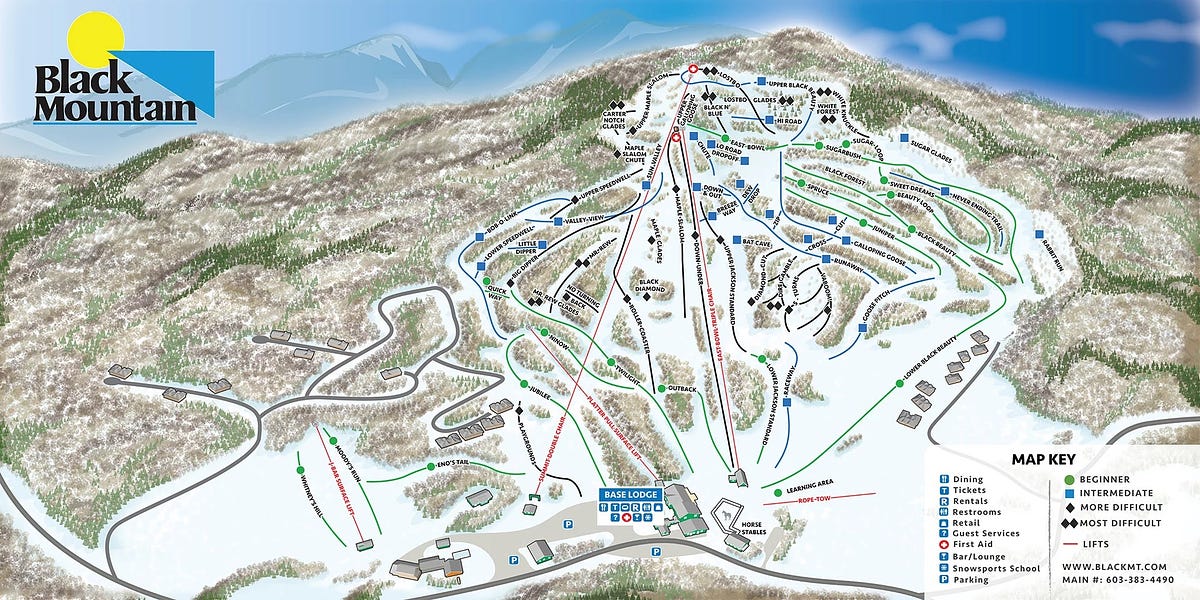

Vertical drop: 1,100 feet

Skiable Acres: 143 acres

Average annual snowfall: 125 inches

Trail count: 71 (10 Expert, 17 Advanced, 24 Intermediate, 20 Beginner)

Lift count: 5 (1 triple, 1 double, 1 J-bar, 1 platter pull, 1 ropetow – view Lift Blog’s inventory of Black Mountain’s lift fleet)

The best description of Black Mountain that I’ve read comes from Skibum.net:

Black Mountain calls itself “A New England Classic,” and rightly so. Ever wonder why 99 mountains out of 100 have a dopey trail called “The Thruway” or “The Turnpike” or some similarly-named avenue that cuts across the face of the mountain — including most of the expert trails — and presents a steady roadblock of cross traffic? Black Mountain has virtually none of this. If you’ve only skied at modern resorts with wide trails, fences, terrain parks and detachable quads, be warned that Black will change your entire perspective on ski areas. Narrow chutes open into broad meadows. Wide groomers branch into a number of narrow options. Drop off a headwall, skirt into a gorge, around some glades, and out into a field. Find yourself wondering, “how did I end up over here?” You can ski with map in hand all day, then suddenly find yourself on a trail you’d overlooked. It’s glorious. Lifts are slow, but liftlines are non-existent — you’ll make run after run after run. Lift tickets are cheap. Afternoon tickets are even cheaper. The place is usually empty, and the skiing is outstanding. Black Mountain will ruin a lot of other ski areas for you. Stuck in the shadow of Attitash, Cranmore, and Wildcat, Black is overlooked by the crowds. Snowboarders are few and far between. Teenagers and hotshots will hate this place, but intermediates and advanced skiers will love it. Wanderers will call it “small,” but be thoroughly pleased by its variety and quirkiness. Families can’t find a better ski area. For trivia buffs, Black is one of the few remaining ski areas where a chairlift passes over a platter-pull lift. It’s also one of the few places where fencing is minimal, and you can still see beginners unintentionally crash right into the parking lot. Most won’t call Black the best ski area they ever visited, but a lot of people call it their favorite. … Recommend.

Black Mountain is the third-oldest ski area in New Hampshire (after Storrs, which opened in 1923), and Wildcat (1933), and is tied for ninth-oldest in the country*.

Nothing survives that long by accident. Black’s operators over the generations have been smart and scrappy. In the 1940s, Black fended off competition from nearby Cranmore and its top-to-bottom Skimobile by installing the ski area’s first T-bar, according to New England Ski History. Black adopted snowmaking as early as 1957, avoiding the fate of nearby Thorn Mountain, which closed that same year. The ski area’s owners unsuccessfully opposed further development at Cannon in the 1950s. Wily and resourceful as its managers were, the mountain teetered, many years, on the brink of survival. Black only opened for two days during the 1979-80 ski season. It outlasted neighboring Tyrol, which carried a similar profile and vertical drop. But on March 3, 1995, the Black Mountain Development Corp. declared bankruptcy .

Soon after, John Fichera took ownership of Black Mountain.

*Four other still-active ski areas opened in 1935: Badger Pass, California; Heiliger Huegel Ski Club, Wisconsin; Lookout Pass, straddling the Idaho-Montana border; and Soda Springs, California.

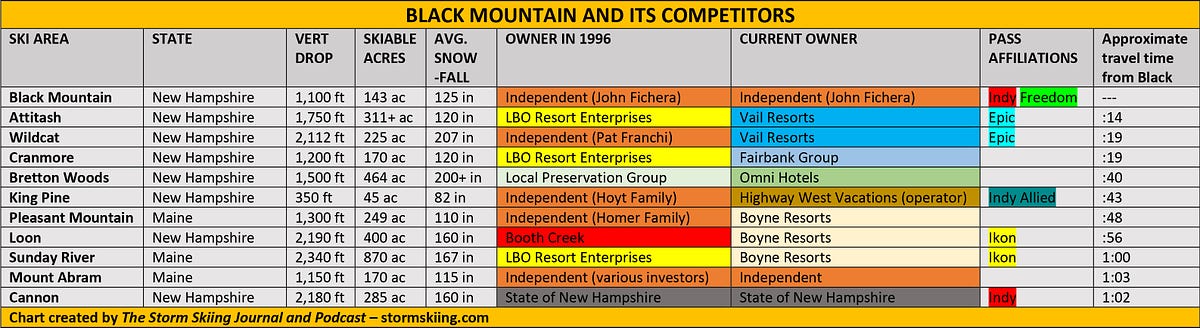

Fichera stepped into a rapidly evolving New England ski industry. Les Otten had consolidated Sunday River, Cranmore, and Attitash into his LBO Enterprises, and the merger with S-K-I – and the subsequent formation of American Skiing Company – was just months away. Loon belonged to Booth Creek – a once-mighty collection of ski areas that, as of 2023, has dwindled to one^. Cannon enjoyed the safety of state ownership. Still, the majority of the ski areas in Black’s immediate orbit – Wildcat, King Pine, Pleasant Mountain (then called “Shawnee Peak”), and Mt. Abram – were all held by families or small groups of investors. Bretton Woods, following a bankruptcy and bank sale, sat under the supervision of a local preservation group.

An attorney by trade, Fichera had never worked at a ski area. He was “just an avid skier,” he says, who grew up skiing Black. He remembers the back pages of 1960s brochures declaring that no ski trip to the Mount Washington Valley would be complete without stops at Black, Cranmore, King Pine, Pleasant, and Wildcat – competitors working together to promote regional strength.

That bonhomie had long since evaporated, Fichera says, by the time he purchased Black Mountain. “By the time I got here in ‘95 with Les Otten and the rest of the crew, they don’t care if you live or die,” Fichera says. “They’d rather have you die because, ‘oh, we’ll just scoop up the business.’”

As years passed and consolidation intensified, Fichera mostly ignored external pressures. Black never had the volume to justify big investments in new lifts (the ski area’s newest chairlift is a 1985 Borvig triple), but he steadily enhanced snowmaking. He did, “every job there is to do here,” he said, from cleaning bathrooms to shoveling sidewalks to operating the lifts.

“I’m out there parking cars and I have a blast doing it,” Fichera says. “Meeting people, ‘Hey, how you doing? What are you doing? Oh no, don’t do that.’ And my dad would help me park cars when he was alive. And it was just, I can’t describe it. I just don’t know. It’s a different way of living and operating. And it’s not just skiing, it’s just a small business model.”

Black ambled along. Then, over the past few seasons, pricing pressures exploded. Fichera’s electric bill tripled. Black’s small reservoirs couldn’t keep up with his competitors’ firehoses sucking unlimited water from lakes and streams. He lost a succession of crucial employees to competing ski areas offering higher salaries – in some cases double what they made at Black. The ski area had still been competitive, with full parking lots and steady revenue, Fichera said, but these pressures piled up.

“I can’t fault ’em for that, because if somebody comes to you and they’re working for you and say, ‘Hey man, I just got a job offer from X and I can double my salary,’ I’m going to go, Wow, great, good for you.’” Fichera said. “And then when they close the door, I’m like, Ugh, whatcha going to do? It is what it is. You always want the best for your help and your guys. So the issue that I finally generated to the boiling point last week was not financial – it was simply staffing.”

Fichera couldn’t see a path forward. His daughter drafted a short Facebook post and published it at 11:18 a.m. last Wednesday morning:

“Right after it went out, I just stuck my head in the sand, leave me alone,” Fichera says. “Just, it’s like a classic shutdown mode. You just don’t want to deal with anything for a few hours or a few days. And that’s where I was. But damned if Erik didn’t call me that afternoon.”

^Sierra-at-Tahoe, California

Erik Mogensen grew up in the suburbs of Buffalo, New York. Seated in a lake-effect bullseye off the western shores of Lake Erie, Buffalo is one of America’s snowiest cities, averaging nearly 100 inches annually.

Young Mogensen, like the Mogensen of today, was obsessed with skiing. Each fall, he would negotiate gear upgrades with his parents, angling to combine his November birthday present with his Christmas present. He always rode ski swap skis. Skiing, he said, took up a huge portion of the family budget for his father and mother, a now-retired autoworker and nurse, respectively. The Mogensens hunted deals: $89 ski-and-stay packages at Okemo, Vermont; Skican packages that compelled the family to drive an hour and a half to Toronto, then park and fly to interior BC.

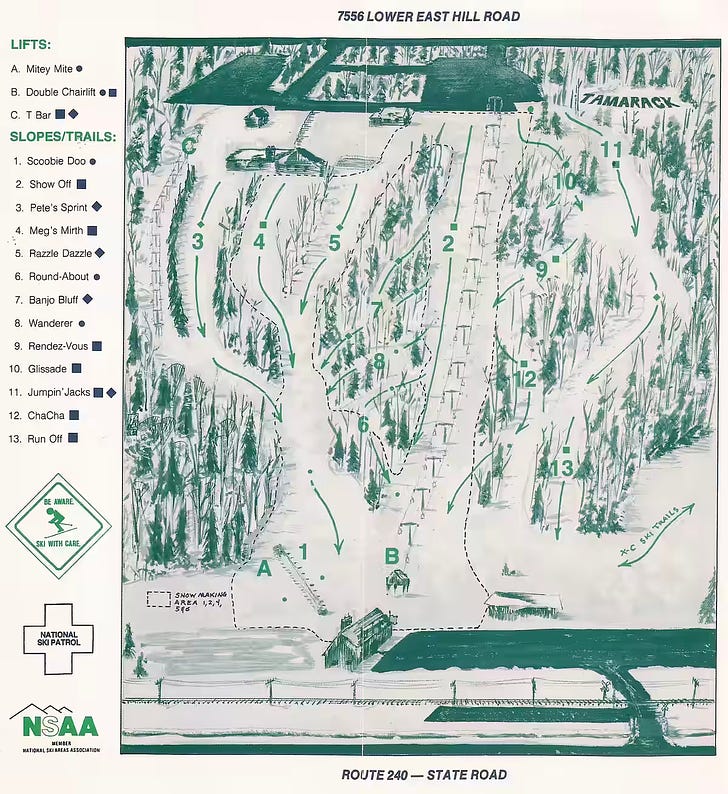

But the family’s ski life revolved around Tamarack, a 463-vertical-foot bump serviced by a 1977 Borvig double chair. It was the personal domain of one Dr. Lore, who would let Mogensen turn the lights off at night, ride in the Snowcat, and tag along with Ski Patrol. Small and underdeveloped as it was, the ski area was Mogensen’s Utopia.

“I wasn’t very happy in the suburbs of Buffalo,” Mogensen remembers. “All I ever wanted to do was go 45 minutes south and go skiing. I used to sleep in the ski instructor locker room on the weekends, and I loved it. It was the happiest thing that we ever did as a family. I think we would’ve been a very different family, and I think my life would’ve been very, very different, had it not been for skiing.”

Mogensen was 16 when Dr. Lore abruptly shuttered the mountain, which he later sold to the private Buffalo Ski Club next door (the modern Buffalo Ski Center also contains the remnants of a third ski area, Sitzmarker).

“It was like my life ended,” Mogensen recalls. “I mean, it was just horrible.”

The family continued to ski at Kissing Bridge, 15 minutes south. But Mogensen found the vibe to be too corporate. And expensive. Many of his friends, he says, simply stopped skiing when they lost access to Tamarack’s $10 Thursday night lift tickets.

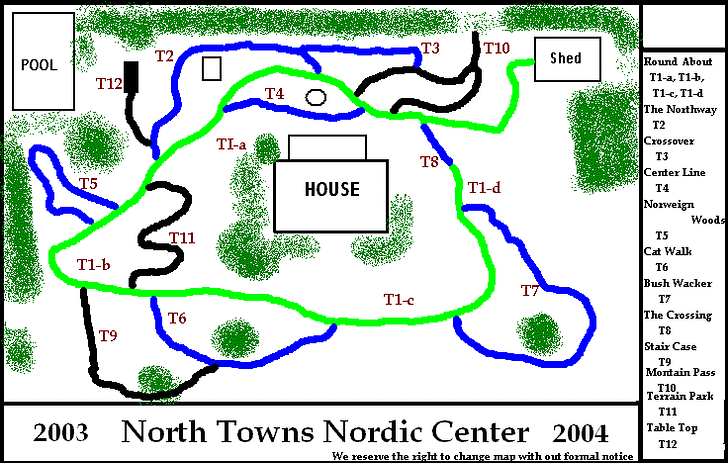

Mogensen grasped for replacements. He spent summers driving New York’s backroads in search of lost ski areas. He built a 12-trail Nordic ski area encircling his suburban home, complete with an improvised snowmaking system, night-skiing lights, a trailmap, and an online system to sell day passes. According to the website, which is still live, North Towns Nordic Center operated an astonishing 137 days over the 2003-04 ski season, closing on May 5.

“I blew the relief valve and the water system because I’ve got too much air and blew back into the house,” Mogensen says. But his parents were supportive. They understood him. “Literally this is what I was put on this planet to do.”

Indeed. Mogensen found work in skiing, spent two years guiding in Chamonix. Over time, he moved into the tech realm and founded Entabeni, which builds software and hardware exclusively for small ski areas, often, to start, for free. His mission is to close the gap between the capabilities of small ski areas and their larger rivals. As Vail and Alterra had built global networks of destinations on their mass-market passes, Mogensen says, they had also massed armies of engineers and data-scientists to read and act upon skiers’ tendencies. Not only were small ski areas not collecting data, most had failed to assign any value to it at all.

“You have to put a value behind the data,” Mogensen says. “That’s one. Two, once you value it, you have to collect it. And so you need systems in place that collect it. And then none of that is really worth anything unless you can analyze the data, which is very different than collecting it. And then finally, once you analyze it, the fourth step is you have to do something with it. You have to make decisions on it and all four are required. If you do two of them and not the other two, it doesn’t matter. The result’s the same. So I knew I had to build a team and a style of thinking and technologies that would help the smaller places do those things.”

When he read a SAM story about the launch of Indy Pass in March 2019, Mogensen called Doug Fish, the pass’ founder. Fish already had a handshake deal with a potential tech partner, but Mogensen was persistent. He offered to build the software for almost nothing, and eventually flew to Portland to meet Fish for breakfast.

“By the time that breakfast was over, I knew Entabeni was a potential buyer for the Indy Pass.”

Four years later, Entabeni closed on a deal to buy Indy Pass from Fish.

“Erik’s not just doing this to make money,” Fish, who remains Indy Pass president, told The Storm. “I mean, he’s a good operator and he’s a good businessman and everything, but he could make a lot more money doing high-tech stuff. But he’s passionate about skiing, and he has been since he was a kid. He’s fearless. He’s driven. And he won’t take no for an answer.”

Mogensen believes that up to a quarter of America’s ski areas need to be converted to nonprofits over the coming decades. The distribution of revenue between family-owned independents and corporate giants, he says, is too unbalanced.

This simmering dynamic will, Mogensen believes, inevitably lead to more announcements like Black’s Oct. 11 Facebook post. Last Wednesday, as he digested the news that a ski area that had been in continuous operation since the Great Depression, that was surrounded by Epic and Ikon resorts, that personified the funky asymmetry of Indy’s archetypal resort, would succumb to not just the macroeconomic pressures of rising energy and labor costs, but the ruthless business logic of distant corporate operators, his reaction was clear and visceral.

“I felt that Black Mountain closing was unacceptable,” he said. “What I thought to myself is this was fucking unacceptable, right? It’s unacceptable. I live in Colorado, and all I see is I-70 jammed with people with Ikon and Epic Passes, and a three-bedroom condo at Beaver Creek is $4 million. And I just think it’s unacceptable that those things can continue to happen, but we can’t have a ski area stay open that provides affordable skiing and access to outdoor recreation.”

And that’s when he called Fichera.

Fichera can’t say for sure what made him pick up Mogensen’s call last Wednesday. He’d been on and off the phone with his daughter all day. “Every time my daughter would call, she’d cry, and every time she’d cry, I’d cry.”

But in a string of brutal winters, punctuated by rained-out Christmases, the abrupt Covid shutdown of 2020, the advent of dirt-cheap local Epic Passes, a public feud with the Ski The Whites uphill organization, and relentless pricing pressures on all parts of the business, Indy Pass had been a constant positive for Black Mountain.

“I love the [Indy Pass] group,” says Fichera. “I think they’re terrific. They do great things for skiing. People that come here with Indy passes when I’m running a lift, I’m looking at their tickets. I’m just like, ‘oh, thank you for coming to see us,’ and they say, ‘This is great. We’ve never been here before. We think this is great.’ I said, ‘well, there you go. That’s what I’m looking for.’ It gives you that feeling that it almost brings you to tears.”

A per-visit payout accompanies those good vibes. When Indy mailed Fichera his first check, following the (otherwise disastrous for everyone), 2019-20 ski season, the operator called Fish to report that the payout was too large. Fish laughed and told him to go deposit the check. That Indy check has grown each year, Fichera said, and was approximately 20 times larger this past ski season than for that first one.

So, perhaps out of goodwill, he took Mogensen’s call last week. They’d never spoken before, but the two talked for 45 minutes.

Fichera had slid into hopelessness. “Erik asked me, ‘what are you going to do?,’” Fichera recalls. “And I said, ‘nothing. What can I do?’ I’m this little old short guy that’s got no hair left. And I’m not in a position where I can drive a Cat, make snow, run a lift, climb a tower. No. A negative. I can’t do that anymore. I’m too old for this game.”

Mogensen, sensing the frustration, listened.

“We talked about the staffing shortages and everything else that was happening, and I tried to understand what the issue was,” Mogensen says. “You never know. Maybe he had a massive lawsuit that finally was going to break the bank, or maybe he couldn’t get insurance coverage, or maybe there was something else happening, but none of those things were the case. There were just too many little things that kept piling up.

“I think at that point, John definitely didn’t think that there was a solution. I don’t think anybody thought that they were going to reverse that decision. But before we hung up the call, I said to John, ‘I’d like to take a crack at a solution here.’”

Fichera didn’t say no.

The next few days, Mogensen says, were a blur. His first call was to Fish. “We have to figure out a way to not have this happen,” he recalls saying. “There are too many passionate people on the Indy Pass to let something like this happen.”

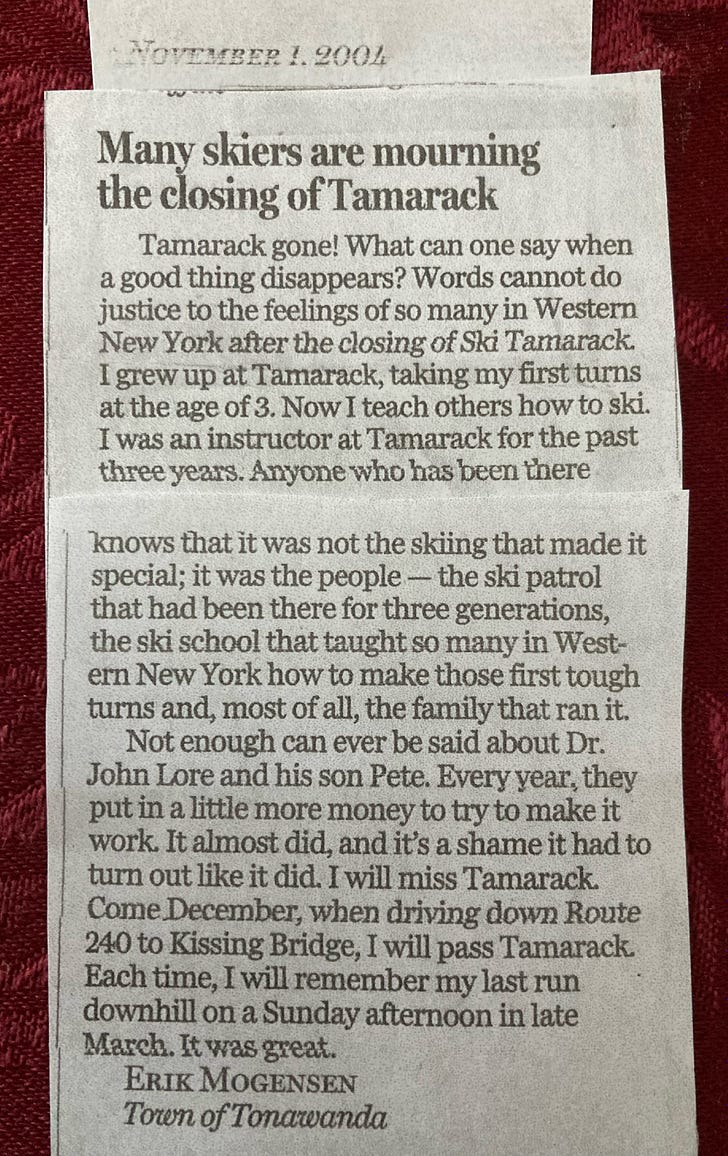

Somewhere, Mogensen knew, the 2023 White Mountains version of his 16-year-old self sat helplessly mourning the loss of their wintertime home. When Tamarack had shuttered nearly 20 years before, teenage Mogensen had written a letter to the Buffalo News:

Nearly two decades later, those feelings of abandonment were still raw. Seeking a way out, he asked his team to rifle through all the data they had about Black Mountain: four seasons of Indy Pass redemptions. He was on the phone constantly, with Fichera, with local ski area operators in New England, with nonprofit organizations. Several things became clear very quickly. Entabeni, Mogensen was certain, was not a buyer. Purchasing every distressed ski area was not, he said, a “sustainable solution.” Second, Black could not be a charity case – though Entabeni was willing to offer temporary financial assistance, the mountain had to find a way to either turn a consistent profit, or operate as a nonprofit. Third, it would take time to find a buyer. Fourth, and perhaps most important: in order to attract the widest possible spectrum of potential buyers, Black Mountain had to open for ski season.

“I realized that if we were going to do this, that place had to open this year, because it’s a lot easier to sell it when it’s a going concern than when it’s not,” Mogensen said. “And so then the thought became, how do we keep this place open this year? How do we essentially create some more runway to find a meaningful long-term solution? And I think it was the next day that I talked to John again and basically made a plea to put his life on hold for another 200 days so that we could create some more runway and sell the place.”

Fichera agreed. But the cold logic seemed to sway him less than Mogensen’s earnest concern for the future of Black Mountain. “The part that I found the most intriguing about his conversations and his presentation to me is he’s genuine,” Fichera said. “He genuinely believes in the independent ski area, and he genuinely was saddened by the potential loss of this little crazy place. And you got to say to yourself, ‘Wow, there’s people out there that think like you. And there’s people out there that believe in you.’”

None of which solves Fichera’s essential problem: the lack of what he calls “specific technical staffing that we need to operate.” Mogensen has pledged to help fill critical managerial and technical staffing gaps.

In the meantime, Mogensen needs to find a new owner. New England is thick with talented ski area managers, with ski enthusiasts, with money. But identifying the person or group of people with the right combination of these traits is a bit like sniffing out truffles. You need the right dog.

Mogensen called Andy Shepard.**

**Disclosure: I introduced Mogensen and Shepard, who has appeared on The Storm Skiing Podcast, via email. I was not party to any subsequent conversations or agreements.

Bigrock, a thousand-footer in far-northern Maine, had failed. It was January 2000, and Andy Shepard was a retail merchandise manager, helping L.L. Bean open stores in the Mid-Atlantic. As the Maine-based company established a nationwide footprint, it looked to kick some of that influence back into the state’s rural corners, boosting otherwise sclerotic local economies. The task fell to Shepard, who founded and led the Maine Winter Sports Center, which, with grants from the Libra Foundation, purchased Bigrock.

Over half a decade, the organizations poured “somewhere around $9 million” into the mountain, Shepard says, updating infrastructure and modernizing its business model and marketing plans. He repeated the effort with Quoggy Joe, a ropetow bump 20 miles north, and Black Mountain of Maine, a scrappy, underutilized hill seated half an hour east of Sunday River.

In each case, Shepard assembled a board of directors from the local community. He formed a separate 501c3 nonprofit organization for each ski area. “I wanted the communities to feel a sense of ownership, to feel a sense of pride in the progress that they made,” Shepard told The Storm. “And if I did this right, the feeling would be that this was a community success, not a Maine Winter Sports Center success.”

It worked. Quoggy Joe replaced its antique ropetow with a T-bar. Black Mountain of Maine roughly tripled its vertical drop, running a chairlift to the summit that opened the ski area’s broad flanks to a corps of hardcore glade-thinners, who, operating under the “Angry Beavers” codename, have quietly undertaken one of New England’s largest trail-network expansions over the past decade and a half. Three potentially lost ski areas were thriving.

It nearly all collapsed in 2014, when the Libra Foundation, miffed, Shepard says, by a dispute with one of the mountains, suddenly pulled funding and demanded that all three be sold off for parts and never re-open as ski areas. He had to save the ski areas all over again. In a scramble of fundraising and bureaucratic re-ordering, he turned each one over to groups of locals, who continue to operate all three today.

Around this time, Saddleback, the third-largest ski area in Maine, suddenly shuttered. Working largely pro bono and in a loose partnership with Portland-based attorney Tom Federle, Shepard jump-started the capsized battleship. In 2020, the ski area re-opened under the ownership of Arctaris, a Boston-based “impact fund” focused on economic development in underserved communities, with a brand-new high-speed quad to the summit. Shepard acted as the ski area’s general manager for its first two seasons, before shifting his focus into community development.

No individual has done more to preserve more New England ski areas over the past two-plus decades than Andy Shepard. No one has a better sense of the importance of even the most decrepit ski area to a community’s sense of worth and identity, and no one has more experience uniting those communities around their shared interest in keeping the lifts spinning. No one, in other words, is better positioned to stake out a sustainable path for Black Mountain, New Hampshire.

“Black Mountain is one of the more historic ski areas in the country, not just in the East or in New Hampshire,” Shepard says. “John should be celebrated and honored for the role he’s played in getting Black open again and keeping it open through very difficult times.”

The mountain’s profile, Shepard says, is similar to those of Bigrock and Black Mountain of Maine, with around a thousand vertical feet and similarly aged infrastructure (parts of the mountain’s J-bar lift date to the ski area’s opening in 1935). But the local community is, from Shepard’s perspective, perhaps better suited to stage a rescue of the local ski area than some of the more far-flung towns he’s worked with in the past.

“What’s different about this is that, while Jackson shares the sense of community that the other places I’ve been have shared, they also have the business,” Shepard says. “There are a number of people in that community with the business background and with the financial capacity and the time to take on a project like this. So I’m hoping to connect with the community, identify those people who want to be a part of the solution, and get to work on figuring out what the next generation of Black Mountain looks like.”

That, says Shepard, could mean municipal ownership, a nonprofit run by a board of directors, or continued life as a scrappy for-profit independent. The community response, with just a few days of poking around, has been, by Shepard’s assessment, “exceptional.” He is confident in his track record, confident in success.

“I enter all these things with a very simple premise, which is it’s too important for this to fail,” Shepard says. “And so you have to take that off the table and move forward understanding that you will succeed. And it hasn’t failed me yet.”

In many ways, the snap resurrection of Black Mountain is an almost clichéd New England story of beloved business closure igniting community shock followed by mass action and (hopefully) salvation. In other ways, however, the speed and scale of the response signals the rise of a new power dynamic in American lift-served skiing, one that grants small ski areas access to the capital, technology, and connections that they have previously lacked.

Five years ago, Black’s decision to close would have shaken skiers across New Hampshire and perhaps across state lines, before the shockwaves died somewhere around the New York border. But in 2023, the ski area’s demise roused a national rescue force, led by an exasperated Mogensen, ready to align his companies’ resources and connections with the Black Mountain Rescue Project.

Neither Mogensen nor Fichera view Black Mountain as possessing an inalienable right to exist. But both believe, after a week of cross-country phone calls, that they can find a sustainable model. That small, independent ski areas, with the right support, can co-exist with giants.

And if Indy Pass and Entabeni can, with the help of an on-the-ground task force, save Black Mountain, then they may, in the process, draw a blueprint that distressed ski areas in Montana or Michigan or New Mexico could follow. The combined companies could, in other words, act not just as promotional and technology partners, but as strategic advisers as well, guiding ski areas in its orbit to sustainable 21st century existence.

But the consumer habits that big, inexpensive passes have stoked will be tough to break, Mogensen says. For Black Mountain and other independents to succeed, a critical mass of skiers needs to reconsider how they approach their ski days and ski seasons.

“This is the piece where everybody hates that Black Mountain closes, but then they go buy an Epic Pass,” says Mogensen. “Ultimately, everybody has to be responsible for a positive outcome.”

The Storm publishes year-round, and guarantees 100 articles per year. This is article 88/100 in 2023, and number 474 since launching on Oct. 13, 2019. Want to send feedback? Reply to this email and I will answer (unless you sound insane, or, more likely, I just get busy). You can also email skiing@substack.com.