Oklahoma restricted how race can be taught. So these Black teachers stepped up

TULSA, Okla. — The schoolchildren arrived at the community center’s cafeteria on a Saturday morning, their parents in tow. Some adults came without children, because they, too, wanted to learn the African American history that a new law has made many Oklahoma schoolteachers too afraid to teach.

Kristi Williams, a leader and activist in Tulsa’s Black community, led them in the pledge they recite each time they gather for a day of lessons.

“We will remember the humanity, glory and suffering of our ancestors,” they said in unison, “and honor the struggle of our elders.”

Williams started offering these lessons early this year, after the state law — adopted by Republican legislators in 2021 — placed restrictions on how race and gender can be taught in Oklahoma’s public schools.

The law has had a chilling effect on teachers who now fear that touching on race and racism in their classrooms could cost them their jobs if a student or parent complains that a lesson made them uncomfortable.

“They’re just staying away from it and not teaching it,” Williams said. “So I had to create a space for families to come in, and teach it.”

She called it Black History Saturdays. It’s one local, grassroots initiative among numerous that have sprung up across the country in places where Republicans have adopted restrictions that make it harder for teachers to discuss race in classrooms.

Williams launched her program – with financial help from the National Geographic Society – out of a resolve not to let Republican politics deny Black children the right to learn honest history about racism and their ancestors’ struggles to overcome it. It’s free for children and adults and meets one Saturday a month.

“We’re reclaiming this,” said Dewayne Dickens, a Tulsa Community College professor who Williams recruited to teach the high schoolers in her program. Restoring honest race history to the state’s public schools is critical, he said, but the Tulsans showing up for Black History Saturdays are also declaring that “we can teach our children, we can teach ourselves, and we can do it better.”

The law’s chilling effect was immediate

The Oklahoma law – H.B. 1775 – lists several “discriminatory principles” that teachers may not include in lessons. They include: that one race or gender is superior to another, that a person’s race or sex make them inherently racist or sexist, that someone bears responsibility for what someone of their race did in the past, or that anyone should feel guilt or discomfort because of their race or sex.

The bill drew immediate criticism from educators who said they have never taught those principles, but who said the ambiguously worded law was designed to scare them away from race lessons that might make children – especially white children – feel uncomfortable.

“The vagueness in the law means that teachers never know what trap they’re going to fall into,” Williams said. Those found to have violated the law can be stripped of their teaching certifications. In a state where the history of anti-Black and anti-Native American racism runs deep, teachers said they felt muzzled.

And the self-censorship started almost immediately.

Angela Mitchell was a first-grade teacher at a Tulsa school with mostly African American students. Teachers there were deliberate about stressing the concept of “Black excellence” as a way to motivate them.

“But when that bill passed, the first thing they told us was that that had to stop,” Mitchell said. She said her school’s administrators were concerned that a parent or child might complain that by emphasizing Black excellence, teachers were suggesting that Black students were better than others, in violation of the state law prohibiting teaching that any race is superior.

“So yes, all the people at the top had to make the choice that we could not as teachers teach our kids Black excellence,” Mitchell said. “Again, not that one race is superior to another, but simply that you are amazing because of who you are.”

Frustrated by those limitations, Mitchell left that job for a charter school. But she jumped at Williams’ invitation to teach a class at Black History Saturdays.

“It gave me the opportunity to do what I love,” she said, “to teach kids not only the safe information they can get at a public school, but also to dive deep and teach history that even I was never taught.”

In her class last month, she centered her lesson on the Greenwood District, the successful Black business district in Tulsa – often called Black Wall Street — that a white mob burned to the ground during the 1921 Tulsa Race massacre, one of the worst race massacres in U.S History. The assignment for the first graders who showed up: to reimagine Black Wall Street and rebuild it as a paper model.

Free to teach, but not without precaution

Classes at Black History Saturdays are divided by grade level.

In the class for kindergarteners, Areyell Scott had just a single student at last month’s gathering – a 6-year-old girl named Caiya Nemons — so her lesson was individualized. It was on Ruby Bridges, the Black first-grader who in 1960 marched past an angry white crowd to desegregate a New Orleans Elementary School.

“Why did they not like her?” Scott asked?

“Because she was Black,” Caiya replied.

Scott said it was important not to sugarcoat the racist truth behind the lesson – because this is the truth of American history. But she also wanted to leave Caiya feeling inspired by Ruby Bridges’ courage.

“She was able to change the trajectory of what all little colored children could be exposed to, and that’s what we want to show,” Scott said. In the aftermath of the law targeting race education, even a lesson as straightforward as this, she said, might make a public school teacher in Oklahoma nervous of drawing complaints.

Black History Saturdays is a private initiative, so teachers feel free to – and are encouraged to — venture into the uncomfortable terrain around race and racism.

Since H.B. 1775 became law, no teachers in Oklahoma have had their teaching certification revoked. But the State Board of Education did vote to downgrade Tulsa’s accreditation after a teacher complained that an implicit bias training for teachers shamed white people. Some teachers have faced protests from angry parents and calls to be punished under the law.

Kristi Williams said although hers is a private program, she still takes steps to protect her teachers from potential backlash. She does not, for example, require them to be in the photos she sometimes posts to social media.

Many teachers she asked to offer a class in her program politely declined, citing fear of reprisal.

“And I totally understand that,” Williams said. “But the teachers who said yes, they’re on the front lines. And we’re here creating our narrative.”

‘I get to learn more about my culture’

At last month’s Black History Saturday, students learned about tensions within the civil rights movement, about Black leaders who overcame racism to succeed, and about Tulsa’s current search for mass graves containing the remains of victims of the 1921 race massacre.

In the class for sixth graders, teacher Precious Lango led a discussion about how white slave owners had often prohibited enslaved African Americans from learning to read, fearing that education would embolden revolts. Knowledge, Lango told her students, was power.

Did her students think, she asked, that there might be a connection to the law Oklahoma Republicans had passed to limit how race can be discussed in public schools?

Sixth grader Kenya Debose raised her hand.

“They’re taking our history away from us,” she said.

“Yes,” Lango said. “And ultimately they’re taking away our power.”

After class, Debose said that when her grandmother first signed her up for these weekend lessons, she was annoyed to have to wake up early. But she enjoys it now because she learns more about race than she does at her regular school.

“I’ve always been proud to be Black,” she said, adding: “So I’m happy that I’m here because I get to learn more about my culture.”

Her grandmother, Pamela Scott Vickers, is a retired teacher, and said it upsets her that the responsibility for teaching unfettered Black history should now fall to concerned citizens rather than to the public education system.

“It stirs up hurt,” but it is also in line, she said, with a long history of people of color having to band together in the face of oppression. “It is so important for children to understand the struggle of living in a world where people are mean, where they will marginalize you, where they will hate you, unless you are grounded in who you are. And that’s why we’re here.”

9(MDAyMTgwNzc5MDEyMjQ4ODE4MjMyYTExMA001))

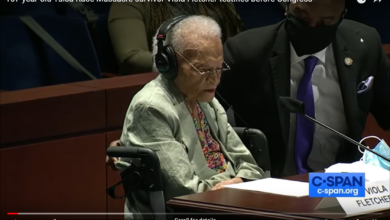

Transcript :

JUANA SUMMERS, HOST:

In 2021, Oklahoma’s Republican-controlled legislature passed a bill restricting how race and gender can be taught in public schools. Teachers found to violate the law can lose their teaching credential, so now many tiptoe around those topics or avoid them all together. In Tulsa, Black teachers and parents weren’t happy that their children might not get access to honest lessons about race, so they did something about it. NPR’s Adrian Florido reports from Tulsa.

ADRIAN FLORIDO, BYLINE: When Governor Kevin Stitt signed that bill two years ago, Kristi Williams, a longtime leader and activist in Tulsa’s Black community, was angry.

KRISTI WILLIAMS: And it’s sad because you’re like, why are people working so hard to keep us from learning about who we are?

FLORIDO: The law prohibits teachers from teaching certain, in the bill’s language, quote, “discriminatory principles” – for example, that a person should feel guilt or discomfort because of their race or gender or that they are inherently racist or oppressive because of their race or sex – things the bill’s critics said teachers have never actually taught. But when Kristi Williams spoke with teachers, they told her the chilling effect was real.

WILLIAMS: So now you have educators who are like, I’m just going to stay away from anything that’s talking about race.

FLORIDO: Williams had been thinking for years about starting a program where kids in Tulsa could come to learn the kinds of lessons in Black history not usually taught in school curricula. The new law finally did it for her.

WILLIAMS: It just pushed me. It was the time. I knew what – I said, I have to make this happen, and so here I am.

(CROSSTALK)

FLORIDO: She called it Black History Saturdays, and it happens once a month in a private community center in North Tulsa. In the cafeteria, Williams stands in front of a few dozen people, parents and their children, all African American, and leads their pledge.

WILLIAMS: We will remember the humanity…

UNIDENTIFIED GROUP: We will remember the humanity…

WILLIAMS: …Glory…

UNIDENTIFIED GROUP: …Glory…

WILLIAMS: …And suffering of our ancestors…

UNIDENTIFIED GROUP: …And suffering of our ancestors…

WILLIAMS: …And honor the struggle of our elders.

UNIDENTIFIED GROUP: …And honor the struggle of our elders.

FLORIDO: Then, the children head off into the classrooms according to their grade.

WILLIAMS: OK, any third- to fifth-graders?

FLORIDO: In the class for kindergartners, teacher Areyell Scott shows Caiya Nemons a picture of Ruby Bridges, the little girl who desegregated a public elementary school in New Orleans in 1960.

AREYELL SCOTT: Look up there. Who is that?

CAIYA NEMONS: Ruby Bridges.

SCOTT: Ruby Bridges. And where did she go?

CAIYA: To school.

SCOTT: To school with a whole bunch of what?

CAIYA: White people?

SCOTT: White people. And did the white people like her?

CAIYA: No.

SCOTT: No.

FLORIDO: Scott says it’s important not to sugarcoat the lesson’s racist truth but also to frame Ruby Bridges as an inspiration.

SCOTT: She was able to change the trajectory of what all little colored children could be exposed to, and that’s what we want to show the little girl that’s in our class.

FLORIDO: In another class, Angela Mitchell helps two boys build a paper model of Black Wall Street, the Black business district in Tulsa that a white mob burned to the ground in 1921 during one of the worst race massacres in U.S. history.

ANGELA MITCHELL: So T.T.’s theme park. That’s going to be cool because the original Black Wall Street did not have a theme park.

UNIDENTIFIED CHILD: Oh. What’s – it’s, like, a mini theme park.

FLORIDO: Mitchell likes to motivate kids by emphasizing Black achievement. But even that, she says, was made harder by the law targeting race in education. She taught at a public school when it took effect.

MITCHELL: The school I was working at was actually a school that celebrated Black excellence. But when that bill passed, the first thing they told us was that had to stop.

FLORIDO: One of those principles the law prohibits teaching is that one race is superior to another – again, Mitchell says, something teachers never have taught. But she says her school’s leaders were worried of being accused.

MITCHELL: So yes, all the people at the top had to make the choice that we could not, as teachers, teach our kids Black excellence – again, not one race is superior to another – simply that you are amazing because of who you are.

FLORIDO: Mitchell left that job out of frustration and moved to a charter school. When Kristi Williams was recruiting teachers for Black History Saturdays, Mitchell jumped at the idea. Williams says many teachers she asked, did not, though.

WILLIAMS: They said, Kristi, I love the idea. I really love the idea. But I’m afraid I may lose my certification.

FLORIDO: No Oklahoma teachers have yet lost their job because of the law, but the state Board of Education did vote to downgrade the Tulsa district’s accreditation after a teacher complained that a racial bias training shamed white people. Kristi Williams says that, amid this climate, the kinds of lessons on race that her teachers are offering students outside their normal classrooms are all the more important.

WILLIAMS: The uncomfortable parts, the good parts – they’re getting all of that, and they’re getting to experience it with their families.

FLORIDO: Kenya Debose is a sixth-grader. She says when her grandmother first signed her up for this…

KENYA DEBOSE: I wasn’t too excited about it, especially for waking up early.

FLORIDO: On a Saturday. Her grandmother is Pamela Scott Vickers.

PAMELA SCOTT VICKERS: (Laughter) Yes, she did. She had to get up early. And grandmother Pam – what I wanted to do was say to myself as well as to them – you don’t always do things that are comfortable for you. Sometimes, there’s a sacrifice.

FLORIDO: Now Kenya likes to come, she says, because she learns things she doesn’t at her regular school.

KENYA: I – actually happy that I’m here to learn more from my culture.

FLORIDO: Dewayne Dickens is a community college professor who signed up to teach the high-school class here because he refuses to let Black children lose access to honest Black history.

DEWAYNE DICKENS: We’re reclaiming this. We can teach our children, and we can do it better. That does not preclude the need that it should be part of the public educational system. That is a sad part, but the celebrated part is that we are doing it ourselves.

FLORIDO: What other choice did he have? – he asked. None.

Adrian Florido, NPR News, Tulsa. Transcript provided by NPR, Copyright NPR.