Once a booming strip of black business, Walnut Street faded from Louisville’s memory for failed Urban Renewal | In-depth

LOUISVILLE, Ky. (WDRB) — There is a story in Louisville long faded from view, and time is taking the people who remember it best. It’s the story of what happened to Walnut Street, what we now know as Muhammad Ali Boulevard.

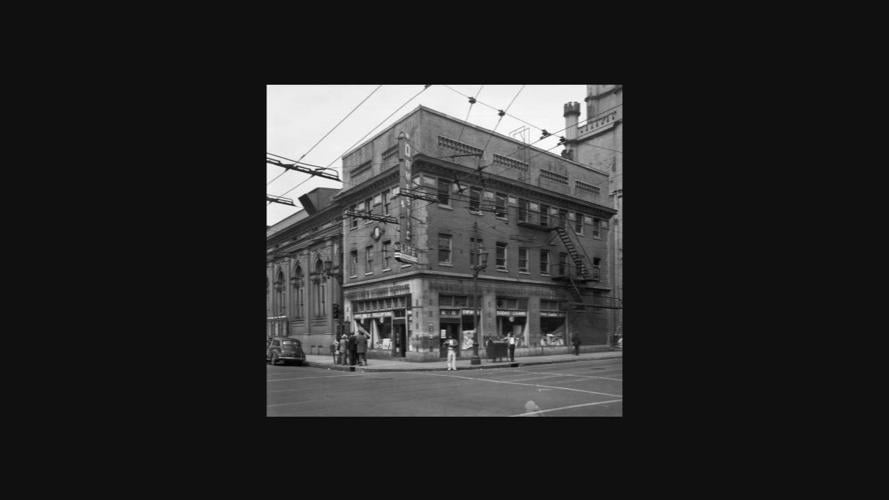

In the days when segregation split the city, Walnut Street between Sixth and Thirteenth streets and the surrounding blocks played host to a booming black business district where African Americans worked, shopped, lived and owned stores.

“This was the hub of the black community,” famed sculptor Ed Hamilton said. “I will never get Walnut Street out of my blood. Growing up there was just phenomenal for me.”

Hamilton’s parents owned Your Valet Shop. His mother was a barber and his father a tailor.

“She was a pioneer back in those days, because women weren’t barbers. They were beauticians,” Hamilton said. “I remember playing around in that shop with my father’s buttons and in boxes — just great, great memories.”

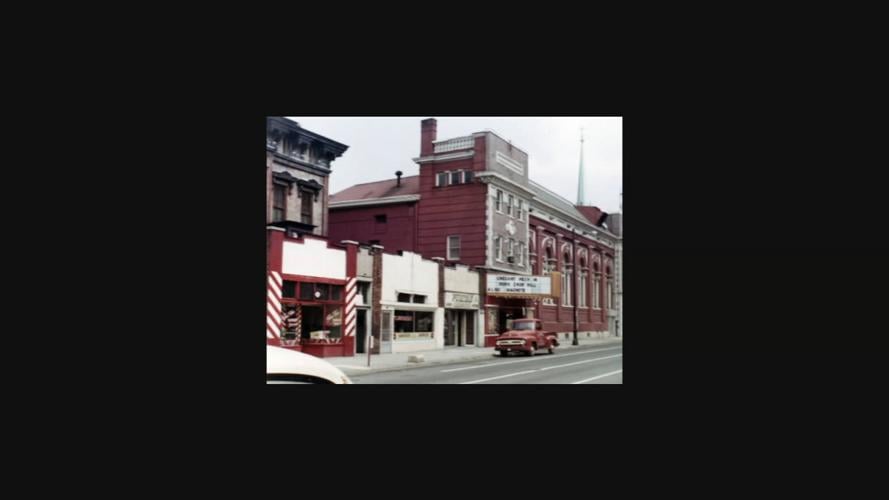

Your Valet Shop was located in the Mammoth Life and Accident Insurance building at Sixth and Walnut streets. Mammoth Insurance was one of the largest black owned businesses in the state.

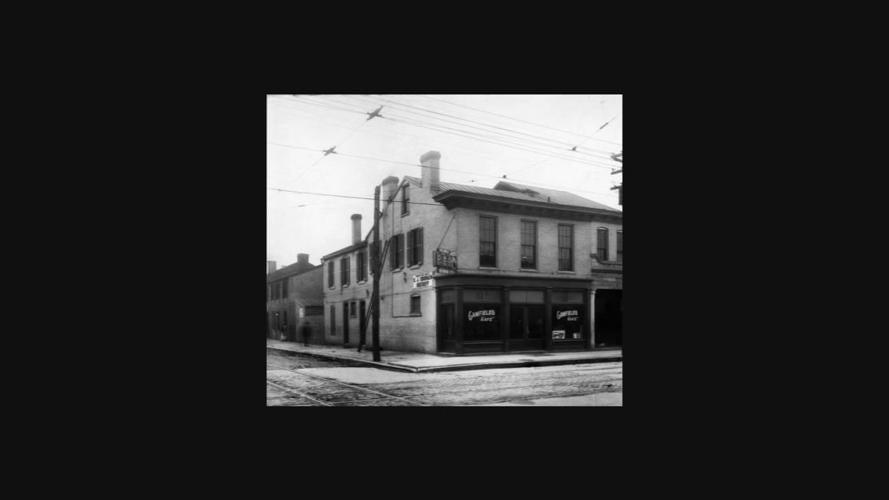

Historians say the 1930s through the 1950s saw Walnut Street at its best. City directories listed 154 black-owned businesses in 1932 alone. The community supported two black-owned newspapers, several theaters as well as offices for doctors, attorneys and dentists and a thriving entertainment and nightclub scene.

“It just made us feel complete,” said Rev. Dr. Geoffrey Ellis, a 79-year-old retired Asbury Chapel AME pastor. “Business and fellowship … gave African Americans a place to belong.”

White people owned businesses and shops on Walnut Street as well.

“I can’t put a value on what Walnut Street meant to me,” said 98-year-old Sonny Bass as he held a book with a picture of his father’s clothing store at 10th and Walnut streets. “It meant so much to me. I’m telling you what’s in my heart.”

Photo courtesy University of Louisville Archive

A similar affection can be found across cultures, but Walnut Street had a different significance for African Americans in terms of economy.

“Everything was on Walnut Street,” 89-year-old Elmer Lucill Allen said. “You could walk up and down the street, and you’d feel safe. It was a different time.”

Restaurants like the Chili Parlor and Buckahart’s were often spoken of along with the likes of lyric and grand theaters and clubs like Charlie Moore’s Joe’s Palm room. In fact, it seems like people can almost still see what used to be on Walnut Street in their mind’s eye.

Such esteem for yesteryear prompted historian and author Kenneth Clay to put together a once-a-year throwback event called “A Night At The Top Hat.”

“The Top Hat Club was probably the most popular, most famous club on Louisville’s Muhammad Ali Boulevard, formerly Walnut Street,” Clay said. “Walnut Street was the heart and the pulse and the soul of the black community.”

Clay compares Walnut to Bourbon Street in New Orleans or Harlem in New York. Likewise, the Top Hat Club, once located at 13th and Walnut streets, brought singers, musicians and crowds from all over.

“Oh yes, I remember the Top Hat,” Allen said with a smile on her face. “Even though I didn’t drink, I could go in, sit down and enjoy myself.”

“We celebrate this institution, because in a way, it meant as much to the black community as churches and schools,” Clay added.

History was not kind to this street remembered with such love. In the 1950s and 60s Louisville embraced Urban Renewal, a federal program designed to tear down old properties and build back something new. The wrecking ball swung hard, forcing businesses to close and families to move.

“They separated it like a bomb that just blew up in the area, and it never came together again,” Clay said.

By the end of the 1960s, the eight blocks of Walnut Street and those surrounding it at the heart of the black community had been flattened.

“It totally took away the aspect of being a part of a community of people who took care of each other,” Ellis said. “If it didn’t destroy it, then it wrecked it to a place where it hasn’t come back yet.”

Many businesses moved but didn’t survive, and the city’s plan for building something better never achieved its goal. In fact, much of the precious land that once was filled by businesses on Walnut Street is now part of city projects or public housing complexes for the poor.

“A pattern of generational poverty set in that’s been so hard to break,” said Kevin Fields, president and CEO of Louisville Central Community Centers. “It severed the economic connection between the business district and all of west Louisville.”

History doesn’t just tell what happened. Some voices tell us why.

“The motive, as they told me, was to drive the negro back from the central area. They felt, that way, downtown wouldn’t become the black belt,” Former Louisville Mayor Charles Farnsley said in an interview for the 1970s documentary “In the American Way.” “It was a cruel thing, and later … Urban Renewal was called negro removal by the negroes and the people who were sympathetic with them. And that’s what it was. It almost always tore down the homes of black people or poor people.”

Metropolitan cities throughout the country struggled with similar urban renewal woes much like Louisville. The demolition of Walnut Street fostered what we now call the Ninth Street divide. Fields said Louisville has paid the price of Urban Renewal for more than 60 years but believes this error in history is coming to an end. His hope rests on the $50 million revitalization of Beecher Terrance. Directly across from what was the old Walnut Street business district, it became the city’s most high-poverty, low-opportunity and high-crime community.

The rebuild will transform the neighborhood to mixed income and supports a vision for redevelopment that LCCC pushed for years.

“Having a broader vision, not all low-income but mixed-use, and also mixed-purpose,” Fields said. “Because we must bring attractions, amenities and places for people to eat and access entertainment and shop.”

Add to that the Louisville Urban League’s multimillion-dollar sport’s complex about a mile away. It’s expected to attract tourism from throughout the country with high school and college athletes coming to Louisville to compete. It’s all designed to build back what was broken long ago.

“I’m optimistic that’s going to pump more into the black community,” Hamilton said.

The city renamed Walnut Street to Muhammad Ali Boulevard in 1978. One of the few buildings still standing from its heyday is Mammoth Insurance, which is now River City Bank, where Hamilton’s parents owned their store.

“I think it’s coming back,” he said. “I can see images, and I can feel the vibe.”

Copyright 2020 WDRB Media. All Rights Reserved.