Opinion | The Tulsa Race Massacre, Revisited

The lynch mobs that hanged, shot or burned African-Americans alive during the early 20th century sometimes varied the means of slaughter by roping victims to cars and dragging them to death. The killers who re-enacted this barbaric ritual in Tulsa, Okla., on June 1, 1921, committed one of the defining atrocities of the Tulsa Race Massacre, the bloody conflagration during which white vigilantes murdered at will while looting and burning one of the most affluent black communities in the United States.

The helpless old black man who was shredded alive behind a fast-moving car would have been well known in Tulsa’s white downtown, where he supported himself by selling pencils and singing for coins. He was blind, had suffered amputations of both legs and wore baseball catcher’s mitts to protect his hands from the pavement as he scooted along on a wheeled wooden platform.

Not far away, in the prosperous black district of Greenwood, white vigilantes systematically torched nearly 40 square blocks. Gone in the blink of an eye were more than 1,000 homes, a dozen churches, five hotels, 31 restaurants, four drugstores and eight doctors’ offices, as well as a public library and a hospital. As many as 9,000 black Tulsans were left homeless. Photographs from the period depict shellshocked survivors being marched at gunpoint to temporary concentration camps.

From Day 1, many Tulsans believed that the authorities had sought to suppress the true horror of the episode by setting the death toll at a few dozen. Others have estimated that as many as 300 may have died. The number of fatalities seems destined to remain a mystery.

Stories emerged featuring bodies stacked up on street corners, ferried out of town on city-owned trucks, burned in an incinerator or dumped into a river. In his 2019 book “Tulsa 1921: Reporting a Massacre,” the journalist Randy Krehbiel unearths a macabre legend that depicts large numbers of dead ground up for use as fertilizer.

Questions that have troubled Tulsa’s sleep for nearly 100 years seemed closer to resolution last year when archaeologists identified two possible mass grave sites, one of them at a city-owned cemetery. History itself seemed to be taunting Tulsans when the onset of the coronavirus pandemic in March forced the city to postpone a test excavation at the cemetery.

When Tulsa resumes the search for its dead, archaeologists should bear in mind Undersheriff Maxey’s portrait of the unnamed dragging victim: an old man with two amputated legs — one stump longer than the other — and a skull bashed in by streetcar tracks.

Running ‘the Negro Out of Tulsa’

Greenwood, whose business district was known as the Negro Wall Street, was the seat of African-American affluence in the Southwest, with two newspapers, two movie theaters and a commercial strip featuring some of the finest black-owned businesses in the country. White Tulsa’s business elite resented the competition all the more because the face of that competition was black. Beyond that, the white city saw the bustling black community as an obstacle to Tulsa’s expansion.

The white press set the stage for Greenwood’s destruction by deriding the community as “Niggertown” and portraying its jazz clubs as founts of vice, immorality and, by implication, race mixing. As was often the case in the early 20th century, a false accusation of attempted rape opened the door for white Tulsans to act out their antipathies.

A black man accused of accosting a white woman in a downtown elevator in broad daylight was predictably arrested, and, just as predictably, a mob convened at the courthouse spoiling for an evening’s lynching entertainment. Black Tulsans who appeared on the scene to prevent the lynching exchanged gunfire with the mob. Outmanned and outgunned, they retreated to Greenwood to defend against the coming onslaught.

The city guaranteed mayhem by deputizing members of the lynch mob — a catastrophic decision, given that Oklahoma was a center of Ku Klux Klan activity — and instructing them to “get a gun, and get busy and try to get a nigger.” The white men who surged into Greenwood may well have been told to burn the district. Greenwood’s defenders fought valiantly but were quickly overwhelmed.

A 2001 report on the destruction commissioned by the Oklahoma State Legislature included a photograph of Greenwood burning. The telling, misspelled caption reads: “RUNING THE NEGRO OUT OF TULSA.”

Writing in the same report, the historian Danney Goble likened the attack to the murderous pogroms that the Russian Empire unleashed on Jewish communities during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. In both cases, the authorities hoped to drive out despised minorities by allowing marauders to kill and loot at will. Mr. Goble argued that the Tulsa massacre was best seen against the backdrop of at least 10 lesser-known pogroms in other Oklahoma towns that had drenched the decade leading up to 1921 in African-American blood.

Two other historians, John Hope Franklin and Scott Ellsworth, described the vast scope of the destruction:

“Practically overnight, entire neighborhoods where families had raised their children, visited with their neighbors, and hung their wash out on the line to dry, had been suddenly reduced to ashes. And as the homes burned, so did their contents, including furniture and family Bibles, rag dolls and hand-me-down quilts, cribs and photograph albums.”

In a less racist judicial system, black Tulsans might have successfully sued the city for encouraging Greenwood’s destruction. But as the legal scholar Alfred Brophy told a congressional hearing in 2007, all-white grand juries in a 1920s-era court system infiltrated by the Ku Klux Klan foreclosed any possibility of justice for African-Americans.

From ‘Riot’ to ‘Massacre’

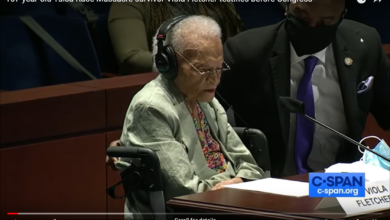

The remarkable Olivia Hooker was 6 years old the day her family’s business, the clothier Elliot & Hooker’s, was rendered down to ash. She grew up to become the first black woman to enlist in the Coast Guard, and she later joined with other Greenwood survivors in an unsuccessful federal lawsuit that sought restitution from the city and state.

Dr. Hooker, a psychologist, offered a harrowing portrait of the massacre when she testified before Congress in 2007. The invaders of Greenwood, she said, raked her neighborhood with machine-gun fire. Her mother pointed to the source of the gunfire and said: “That thing up there on the stand with the American flag on top of it is a machine gun. And those are bullets hitting the house. And that means your country is shooting at you.”

While fleeing the mob, Dr. Hooker’s mother paused to lecture white parents who had brought their children to witness the conflagration. Trained in oratory at the Tuskegee Institute, she intoned that this deed “would be visited upon the children unto the third and fourth generation” — at which point she was asked to stop, because the white children had grown frightened. The marauders stripped the Hooker home of furs, jewelry, silver — and took axes to fine furnishings not easily carried away.

Dr. Hooker died in 2018 at the age of 103. Soon afterward, the commission set up to coordinate centennial activities for what was increasingly referred to as a massacre — as opposed to a riot — changed its name. The 1921 Race Riot Centennial Commission became the 1921 Race Massacre Centennial Commission.

The change reflects lingering resentment over the fact that insurance companies had seized upon a “riot exclusion clause” to deny claims filed by Greenwood property owners. The wording also bespeaks a realization that the assault was a deliberate attempt to terrorize and force black people out of the city.

Bodies ‘Stacked Up Like Cordwood’

Some of the white men who ravaged Greenwood may have convinced themselves that the armed black men who confronted the mob at the courthouse were part of a conspiracy to take over the white city. No such pretense was even remotely available to the killers who roped the helpless pencil seller to a car and dragged the life out of him along Main Street. The event was a carnival of death, staged for their amusement.

This atrocity was given a single sentence in a larger news article about the carnage: “One Negro was dragged behind an automobile, with a rope around his neck, through the business district.” In recent years, however, the incident has become a bloody shorthand for the hatred of blackness that underlay this massacre as a whole.

Consider the critically acclaimed HBO series “Watchmen.” While making a new generation of viewers familiar with this bloody episode, the writers used their version of the dragging as a metaphor for white supremacist violence not just in Tulsa but in the country as a whole.

In 1921, the white civic elite did its best to shield the city from negative publicity by limiting news coverage. Not long after the conflagration, for example, Tulsa’s police chief barred the taking of photographs in the devastated area without police permission — as “a precaution against the influx here of Negroes and other critics seeking propaganda for their organizations.”

The description of the dragging that Undersheriff Maxey shared with Ms. Avery 50 years after the fact offers a window into how this public silencing was achieved. He despised the leader of the killers — who was dead by the time of the 1971 interview — and seemed to have had genuine affection for the pencil seller. Nonetheless, he declined to name the main perpetrator because he “had people” in Tulsa. Multiply this mind-set by the thousands of men who had either participated in the violence or knew someone who had, and you quickly get a sense of how this story was pushed to the margins of public awareness.

Like many other Tulsans, Undersheriff Maxey doubted the city’s suspiciously low body count. During the Avery interview, he spoke of seeing five or six truckloads of black bodies moving up Main Street to an unknown destination. “I seen them haul truckload after truckload of colored people in those things, stacked up like cordwood,” he said. Asked where the dead might have gone, he replied, “I don’t even know that, but they was hauling them out somewhere, I guess, and put them in ditches or something.”

As Tulsa scours the landscape for its dead, the centennial of one of the most destructive episodes of racial terrorism in the country’s history is fast approaching. When archaeologists resume their work, modern-day Tulsans could well learn more about the blood-drenched episode that has haunted the city’s dreams for nearly a century.