The challenges, solutions, and opportunities for prosperity

At a January 17 event marking Martin Luther King Jr. Day, Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen said, “From Reconstruction, to Jim Crow, to the present day, our economy has never worked fairly for Black Americans—or, really, for any American of color.” Yellen’s remarks were an acknowledgement that U.S. policymakers have established racially tilted rules for the economy, prohibiting intergenerational wealth transfers among Black Americans, among many other harms.

According to the Federal Reserve, in 2019, the median net worth of white families was $188,200—7.8 times that of their Black peers, at $24,100. That wealth gap translates to many other disparities, including in business ownership, which is heavily influenced by individual and family wealth. In 2019, there were a total of 5,771,292 employer firms (businesses with more than one employee), of which only 2.3% (134,567) were Black-owned, even though Black people comprise 14.2% of the country’s population.

In support of the Path to 15|55 initiative, which endeavors to grow the percentage of Black-owned employer firms, Brookings published “To expand the economy, invest in Black businesses,” a report that used the Census Bureau’s 2019 Annual Business Survey (ABS) to calculate the national proportion of Black and non-Black businesses in the prior year. The report also calculated the businesses, jobs, and revenue the nation would gain if the percentage of Black-owned employer firms equaled the proportion of Black people in the country’s population.

In this report, we examine those same projections at the metropolitan level using 2018 and 2020 ABS data. (The ABS uses yearly administrative data and representative surveys to compile key economic and demographic information for employer firms and non-employer firms [also known as sole proprietorships], and produces data estimates at the national, state, metro area, county, and economic place level.) Additionally, we explore policy solutions that get at the heart of Yellen’s assertion, recommending structural changes that will enable the economy to work for entrepreneurs of all races.

What metro areas could gain with more Black-owned businesses

Before illuminating the lack of Black-owned businesses in U.S. metro areas and the structural reasons behind it, the interactive below presents the revenue, jobs, and wages that places would gain if the percentage of employer firms that are Black-owned was on par with the metro area’s Black population share.

We assume an expansion in the size of the economy such that no gains in Black business revenue or size come at the expense of non-Black businesses. The estimations are based on revenue and payroll data from the 2018 ABS, as the 2019 and 2020 ABS have limited data on revenue at the metro level.

Black-owned businesses are prevalent in the Southeast, but still far below the Black population share

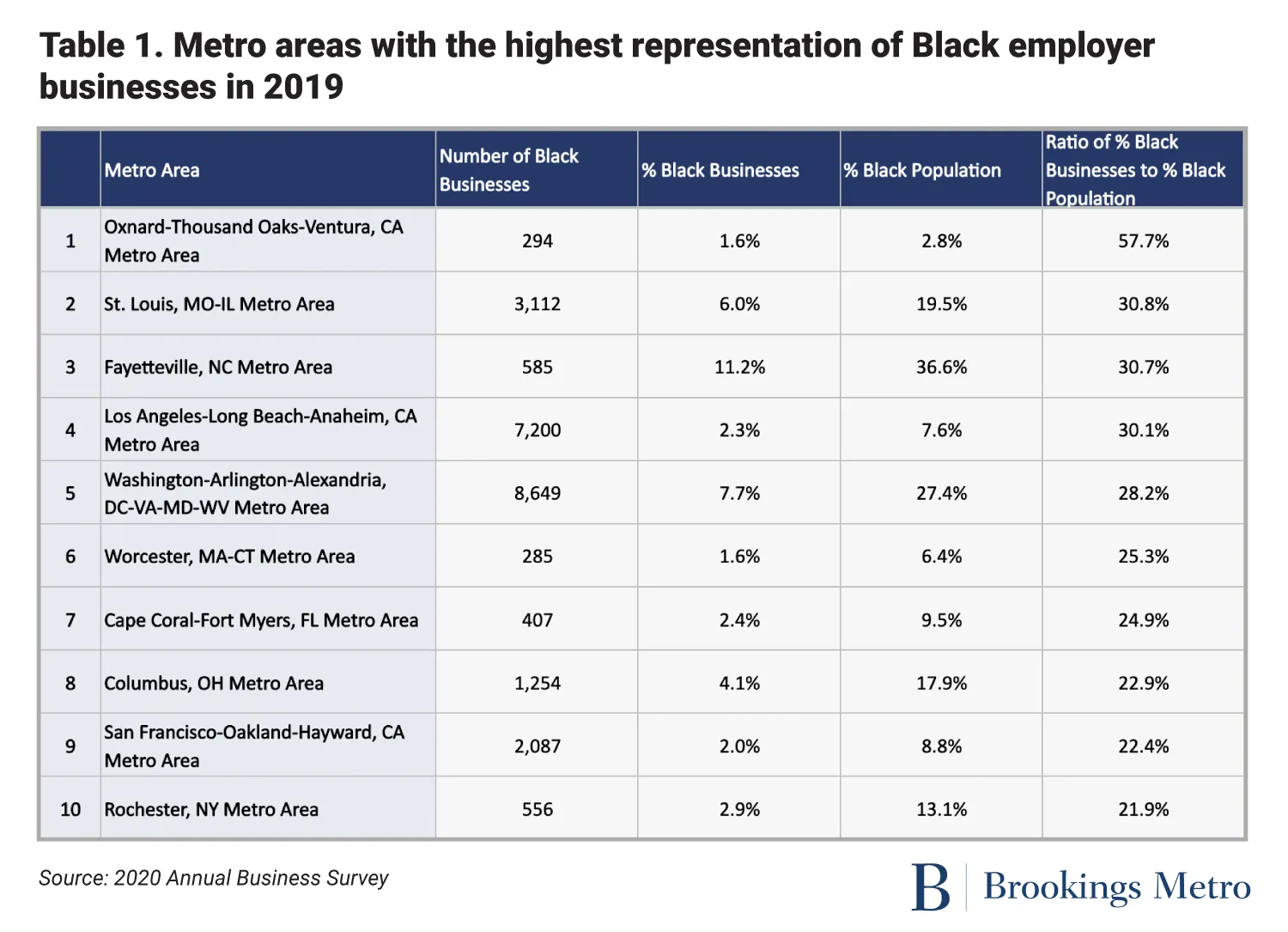

No metro area in the U.S. has a share of Black-owned employer firms that matches or exceeds the Black population in the area. Among 69 metro areas for which the 2020 ABS reports data, the highest proportion of Black-owned firms among employer businesses is in Fayetteville, N.C. at 11.2%, or 585 out of 5,210 firms.

Table 1 displays the 10 metro areas with the highest representation of Black employer firms in 2019. It shows Black entrepreneurs have found a niche in the Southeast, which features a high number of Black residents, a lower cost of living, and a historical lineage of Black people supporting Black-owned businesses.

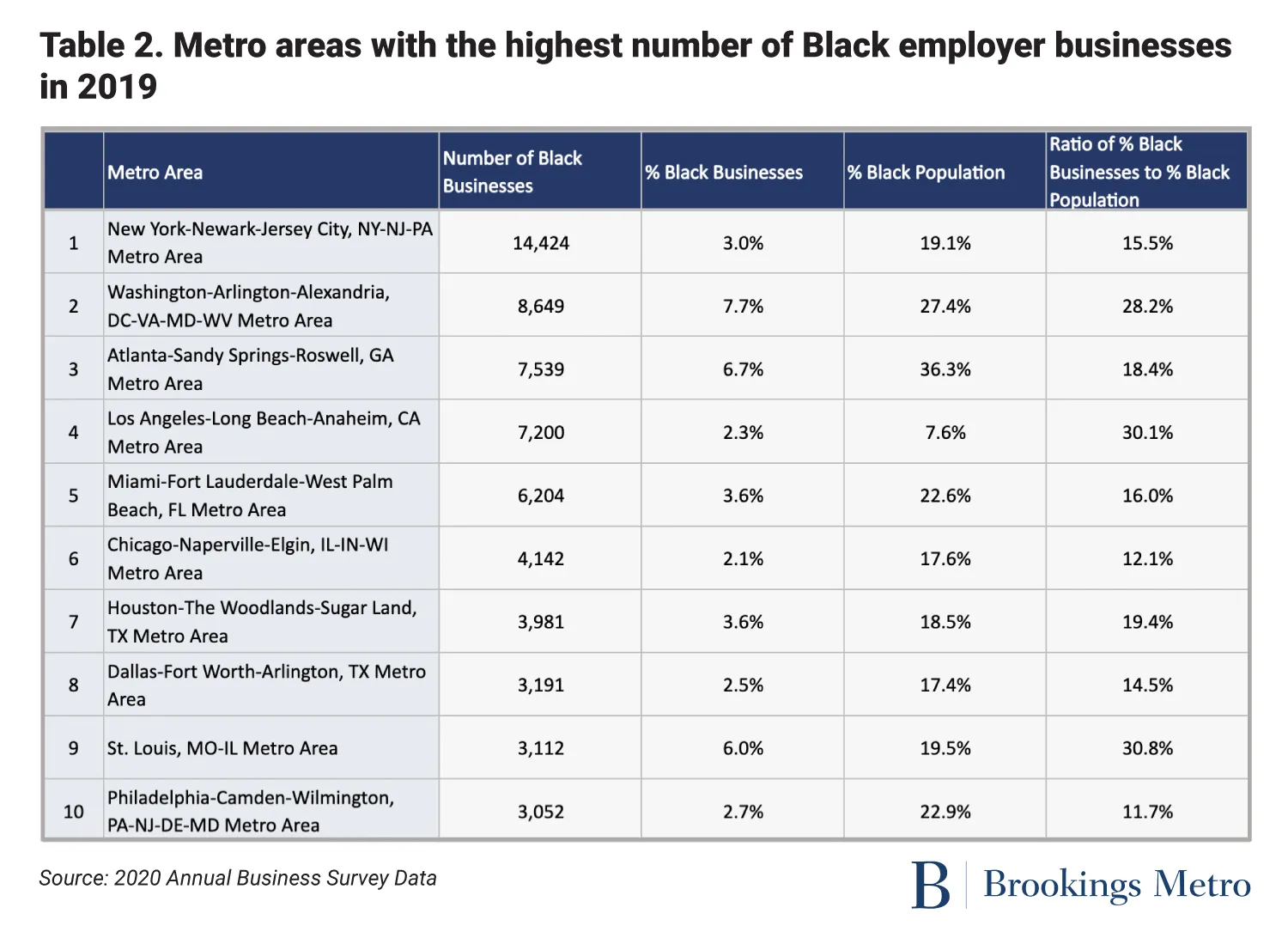

However, in absolute terms, there are more Black businesses in other regions of the country. Table 2 shows the 10 metro areas with the highest number of Black businesses.

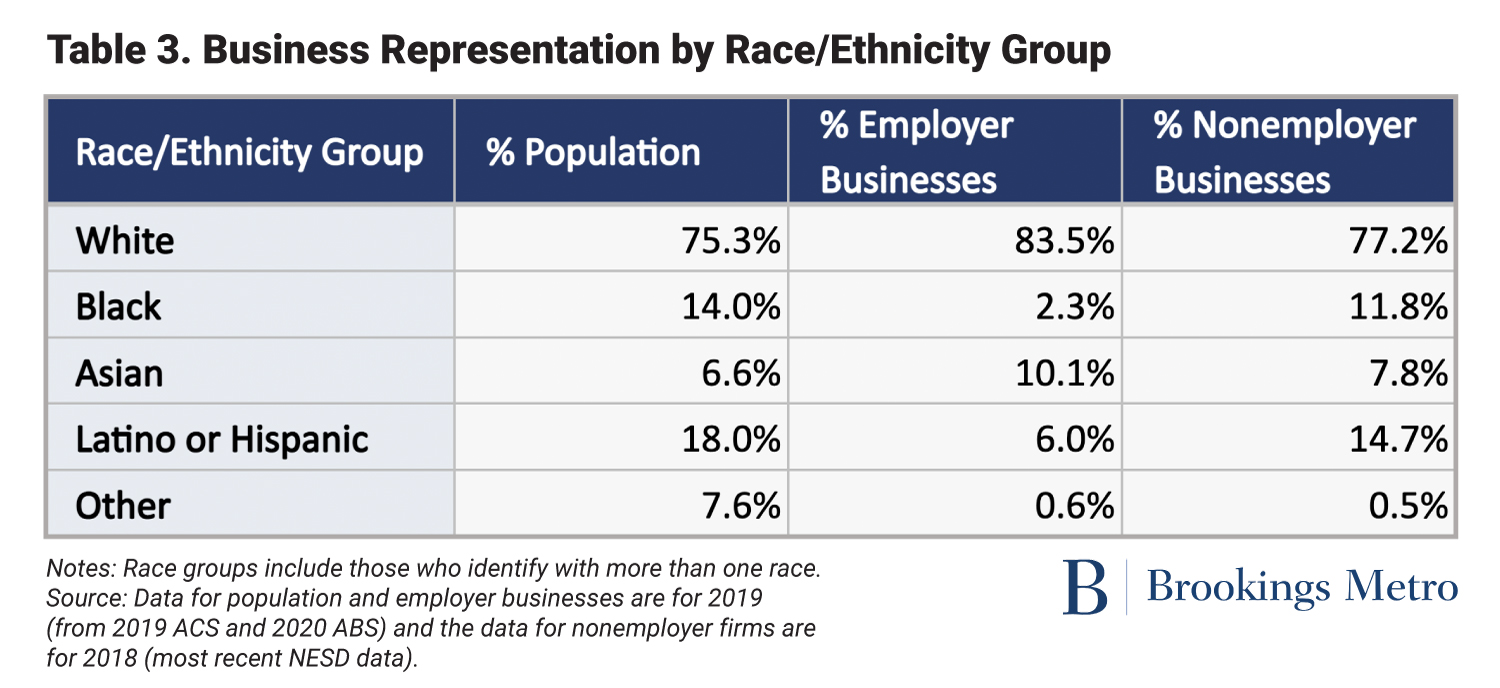

Nationally, as of the latest census data release, there were 3.12 million Black-owned businesses in the United States, generating $206 billion in annual revenue and supporting 3.56 million U.S. jobs. Table 3 shows that Black people comprise approximately 14% of the U.S. population, but only 2.3% of owners of employer firms. White-owned employer firms represent 83.5% of all employer firms—8.2 percentage points higher than the white share of the population. Asian Americans make up 6.6% of the U.S. population and own 10.1% of employer firms.

Black-owned businesses are much more likely to be nonemployer firms (sole proprietorships). In 2019, only 4.1% of Black-owned businesses were employer firms, compared to 19% of white-owned businesses. If Black businesses accounted for 14% of employer firms (equivalent to the Black population share), there would be 798,318 more Black businesses.

The Census Bureau collected these statistics before the COVID-19 pandemic, so many of the figures presented here have undoubtedly changed. As we await updated data reflecting those changes, we can draw upon qualitative sources to get a sense of how the pandemic has impacted Black businesses.

The pandemic affected Black business owners worse than other racial groups

This report uses 2020 ABS data, which was collected in the year prior, before the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic. However, findings from the Federal Reserve System’s 2021 Small Business Credit Survey (SBCS)—which was conducted in September and October 2020—provide qualitative insights into the pandemic’s impact as well as the issues that must be addressed to increase the Black share of employer firms. The SBSC is an annual survey of businesses with fewer than 500 employees, which represent 99.7% of all employer firms in the U.S.

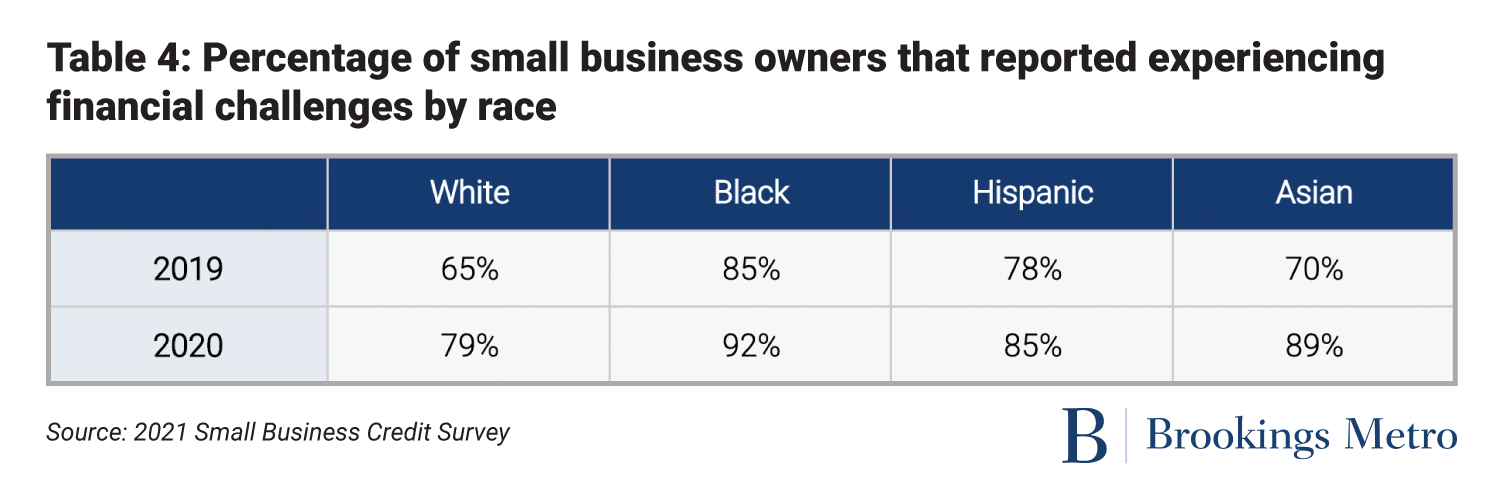

The SBCS reveals that the COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated the challenges that small businesses owned by people of color faced prior to the pandemic. Table 4 shows the percentage of small business owners by race that reported experiencing financial challenges in 2020. Most small business owners reported experiencing financial hardship during the pandemic, but the highest rate was reported by Black business owners: 92%, followed by 89% of Asian American-owned firms, 85% of Latino- or Hispanic-owned firms, and 79% of white-owned firms.

According to the SBCS, approximately 79% of Asian American-owned firms and 77% of Black-owned firms reported that their financial condition was poor or fair, while only 54% of white-owned firms reported similar conditions. Nearly 75% of Black- and Asian American-owned firms reported difficulties paying their operating expenses, compared to 63% of white-owned firms. Black small business owners were also the most likely to experience difficulty accessing credit (53%).

Reduced revenues due to the shutdowns and quarantines forced businesses to adapt their operations. Black- and Asian American-owned firms were most likely to reduce their business operations in response to the pandemic (67% each), followed by Latino- or Hispanic-owned firms (63%) and white-owned firms (54%). In response to financial challenges, Black business owners were the most likely to tap into their personal funds (74%), compared to Latino or Hispanic owners (65%), Asian American owners (65%), and white owners (61%).

Systemic policy failures kept pandemic aid from reaching Black businesses

In March 2020, Congress passed the CARES Act to address the economic fallout of the pandemic. As part of the act, Congress authorized the Treasury Department to disperse up to $659 billion in forgivable loans to small businesses through the Paycheck Protection Program (PPP.) Eligible businesses received loans to cover payroll and certain other expenses (including mortgage, rent, and utilities), and those loans were forgivable if firms retained employees at their current level of compensation.

While PPP loans were an important economic cushion, key flaws meant that the program was largely regressive and not targeted to the firms with the greatest need, particularly in communities of color. One paper estimated that “only 23 to 34 percent of PPP dollars went directly to workers who would otherwise have lost jobs” while “the balance flowed to business owners and shareholders, including creditors and suppliers of PPP-receiving firms.”

Additionally, the first round of PPP loans gave relief only to employer firms. This disproportionately disregarded Black-owned businesses, 95% of which are nonemployer firms, compared to 78% of white-owned firms. When Black businesses did receive PPP loans, the funding arrived much later than for white businesses, and was often substantially less than what was offered to white businesses. “Black-owned businesses received loans through the Paycheck Protection Program that were approximately 50 percent lower than White-owned businesses with similar characteristics,” one nationwide study found. Likewise, the SBCS shows that only 43% of Black-owned firms received all of the PPP funding they applied for, compared to 61% of Latino- or Hispanic-owned firms, 68% of Asian American-owned firms, and 79% of white-owned firms.

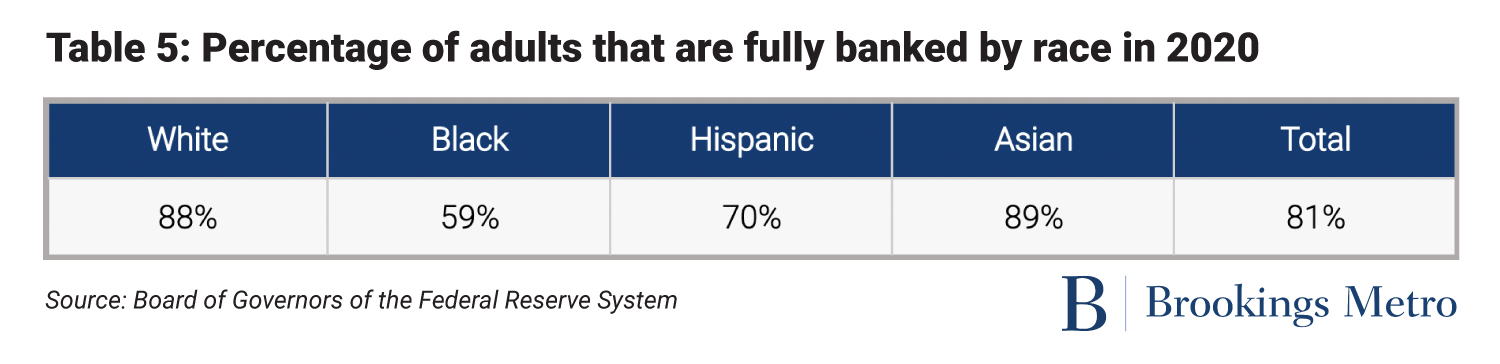

The first-come, first-serve nature of the PPP compelled mainstream banks to work with existing customers. This is a problem because Black people are significantly underserved by mainstream banks and the financial services sector in general. Table 5 shows banking access by race in 2020; that year, only 59% of Black adults were fully banked, compared to 70% of Latino or Hispanic adults, 88% of white adults, and 89% of Asian American adults.

Black business owners’ perceptions of their pandemic hardships mirror the realities. According to the SBCS, 46% of Black business owners reported concerns about personal credit scores or loss of personal assets as a result of late payments—the highest share among owner groups by race. In contrast, white business owners were the most likely to report that there was no impact on their personal finances.

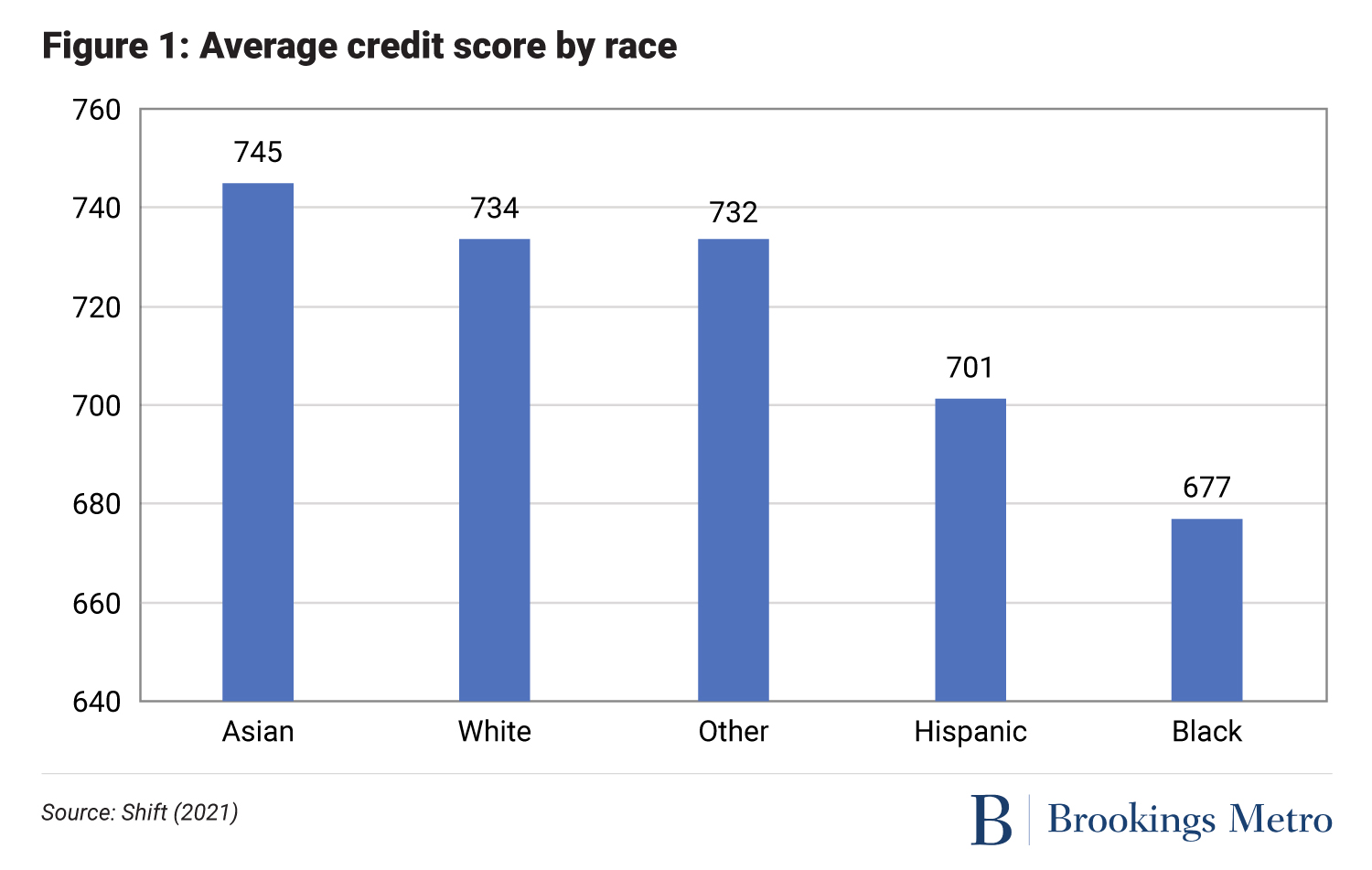

Figure 1 shows average credit scores by race for 2021. Black people had the lowest average credit score, at 677. People with lower credit scores are more likely to pay higher fees to receive financial services and more likely to depend on alternative financial institutions, some of which are predatory lenders.

Nevertheless, many Black businesses had greater luck pursuing loans from non-mainstream banks. For example, in Charlotte, N.C., several Black businesses that were denied loans from big banks were able to secure loans from Uwharrie Bank, a small community bank. Similarly, NPR reported that Savannah, Ga.’s Black-owned Carver State Bank helped many Black businesses that were denied loans from mainstream banks, issuing $9 million in PPP loans within a five-month period. These examples underscore the importance of supporting a fuller range of financial intermediaries when big banks fail to deliver services to all constituents.

The pandemic has led to a surge in new Black-owned businesses

While the pandemic disproportionately hurt preexisting Black firms, it also spurred the creation of new Black businesses. A recent Brookings report found there has been a surge of new online microbusinesses, which grew fastest among groups hit hardest by the pandemic’s economic shock; among racial groups, Black owners account for 26% of all new microbusinesses, up from 15% before the pandemic. And a recent paper from the National Bureau of Economic Research found large upticks in new businesses between 2019 and 2020 in Black neighborhoods with moderate income levels. The paper found a statistically significant correlation between upticks in new business registrations and both rounds of pandemic stimulus checks, with particularly high rates of business formation in Black neighborhoods.

Many commentators have connected the burst in Black entrepreneurship to the loss of employment for Black workers, combined with new opportunities stimulus checks made available. Of the five occupations that employ the largest number of Black and Latino or Hispanic workers, four experienced the highest job losses at the beginning of the pandemic: retail salespersons, cashiers, cooks, and waiters and waitresses.

The use of personal stimulus checks for business creation and the failure of PPP funding to reach Black business owners are two sides of the same coin. Both demonstrate that Black business owners—like Black consumers in general—struggle to access traditional lines of credit and capital, which forces them to seek funding outside of these institutional structures.

For example, a 2019 study from the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta found that Black entrepreneurs are much more likely to rely on personal funds and credit to finance their businesses, and the SBCS study cited earlier found that Black- and Latino- or Hispanic-owned firms were not approved for the full requested financing “even when the Black-owned, Latino-owned, and white-owned firms were all categorized as presenting a low credit risk.” These studies show that Black entrepreneurs face many systemic barriers that rob them of investment and suppress development.

Lower personal wealth inhibits Black business creation

According to a 2018 study by the U.S. Small Business Administration, most entrepreneurs start their businesses using personal or family wealth. But the study finds that Black entrepreneurs are more likely to rely on personal credit cards to finance their business creation. This is due in part to barriers to bank loans and other sources of institutional capital, but is also the result of staggering inequalities that impact how much wealth is held by Americans of different racial groups.

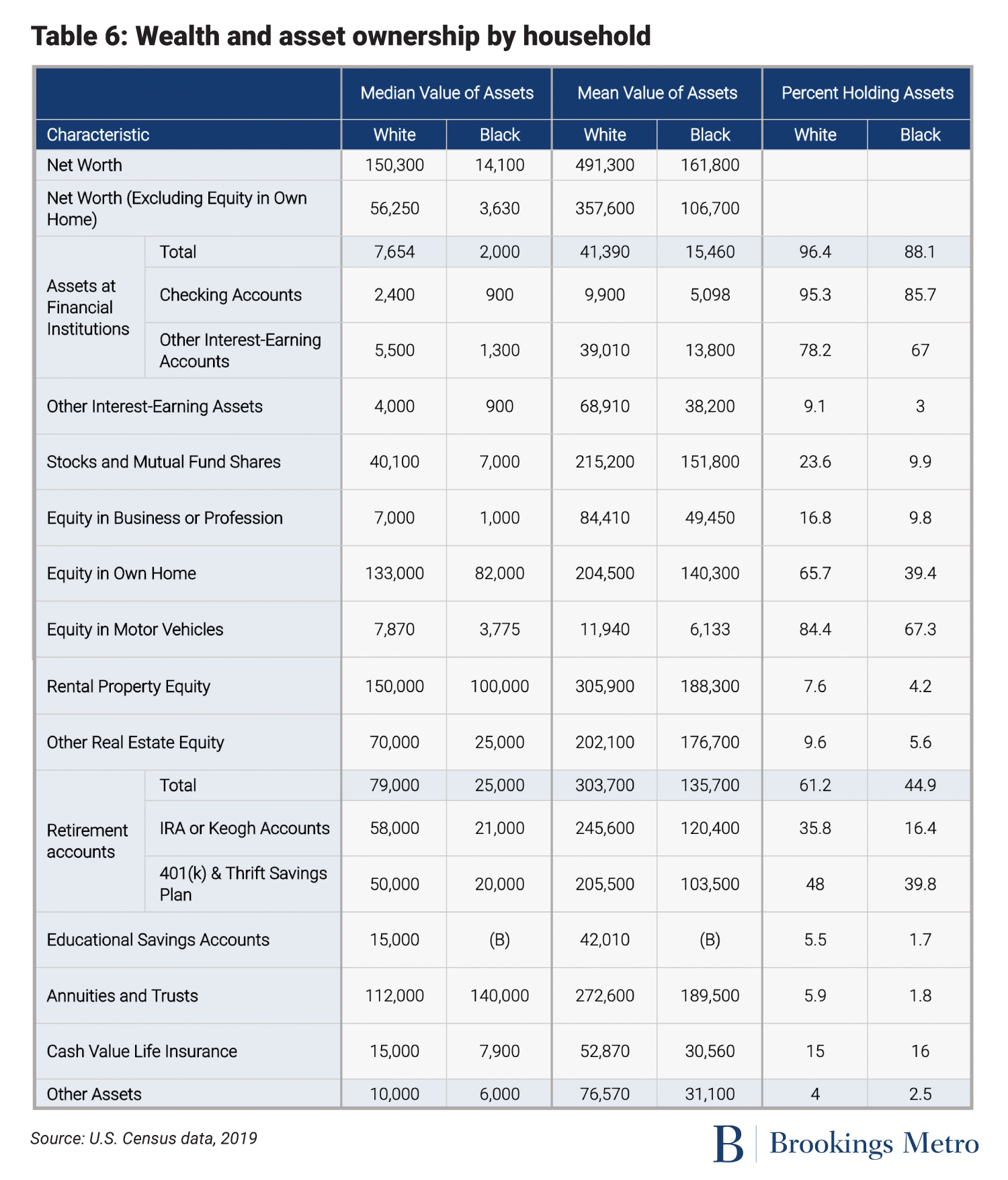

According to our analysis of 2019 Census Bureau data, Black people with positive net worth have assets that are primarily tied up in real estate—mainly homeownership. But in the U.S., the homeownership rate varies significantly by race and ethnicity, and is lowest for Black people. According to the Census Bureau, in the third quarter of 2020, the homeownership rate for white non-Hispanic Americans was 75.8%, compared to 61% for Asian Americans, 50.9% for Latino or Hispanic Americans, and 46.4% for Black Americans.

Black families are not only less likely to own a home, but according to Brookings’s Hamilton Project, “their homeownership yields lower levels of assets.” Among homeowners, Black families’ median home value is $150,000, compared to $230,000 for white families. Black people are also underindexed in businesses, stocks, bonds, and other assets that can increase their net worth. In addition, assets that Black people hold have lesser value, lessening their ability to start businesses.

While increasing Black business ownership would certainly have a positive economic impact on Black households and communities, renewed fiscal support from federal, state, and local governments is needed to mitigate the racial wealth gap. Data and research show that on average, Black people have higher unemployment rates, lower earnings, lower rates of homeownership, and pay more for credit and banking services—all factors that result from a history of structural racism and contribute to vast disparities in wealth creation and accumulation between Black households and white households.

Federal and metropolitan policy solutions to expand Black business

There is a causal relationship between discriminatory policy and wealth accumulation, and there is a direct correlation between wealth and business development. Business outcomes reflect a racial wealth gap that is shaped by racialized policies, including those created by the federal government.

We should look at the wealth gap as merely an indicator. “By focusing on the root of racial wealth inequality rather than fixating on the racial wealth gap, we can identify a path forward for creating a fairer and more sustainable economic and political system,” wrote the Roosevelt Institute’s Anne Price in a 2020 report aptly titled “Don’t Fixate on the Racial Wealth Gap.”

Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen’s recent Martin Luther King Jr. Day remark that the U.S. economy has never worked fairly for Black Americans should reverberate loudly in the halls of federal policymaking. Inequality is a choice, and systemic racism involves a constellation of polices that racialize how resources are distributed. But just as systemic racism was built upon unjust policy, it can be deconstructed and replaced. Here are some potential ways to do so:

The Treasury Department should create inclusive and equitable policies

Under the Trump administration, the Treasury Department oversaw and led the Paycheck Protection Program (PPP), which was slow to reach most Black-owned businesses. In 2021, Treasury Secretary Yellen announced that the department would invest $9 billion into the Emergency Capital Investment Program, a new initiative designed to provide capital to community development financial institutions and minority depository institutions—entities that have a better track record of working with the conditions surrounding Black borrowers.

Before the inevitable next economic shock, the Treasury Department should aim to build enough capacity among these financial institutions to avert the PPP’s original failures. The department should lead an interagency taskforce to take a roll call among banked and unbanked Black businesses; to enable these businesses to receive the financial services to participate in capital markets, they must be identified first. In addition, Treasury and the Federal Reserve System should step into their regulatory roles to ensure mainstream banks that distributed PPP funds are ready and willing to serve the range of Black entrepreneurs.

Additionally, the Internal Revenue Service (IRS), a bureau of the Treasury, should closely monitor the impacts of new rules that require reporting of business transactions through apps such as PayPal, Square, Venmo, and Zelle for goods and services amounting to $600 or more in a calendar year. The prior reporting threshold was $20,000 across more than 200 transactions.

These new rules, which will take effect for the 2022 tax year, will most certainly garner greater tax revenue enforcement particularly at the lower end of the business revenue spectrum. This will have a disproportionate impact on Black-owned businesses because of their higher share of nonemployer firms. The new criteria will have a particular effect on “cash only” businesses in informal or underground local economies, such as barbershops, beauty salons, and other neighborhood-facing firms.

This tax code change poses an equity issue because it’s unclear how the IRS will reduce tax revenue loss on the opposite end of the income scale. Owners of higher-revenue-generating businesses have many ways to hide or reduce tax liabilities. The previous higher reporting thresholds provided a tax shelter of sorts for small businesses that were unbanked and under-resourced.

Expand the Minority Business Development Agency and its partnerships

To help the federal government build the capacity of financial institutions that serve Black entrepreneurs, the Commerce Department’s Minority Business Development Agency (MBDA) should be expanded. The MBDA connects minority-owned businesses with the capital, contracts, and markets they need to grow. The recent Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act permanently authorizes the MBDA and provides the agency with a bigger budget and greater grant-making capacity.

Moving forward, the MBDA should use its newly created regional offices to spur a more inclusive innovation economy, such as by providing flexible funding streams for the creation and expansion of Black businesses. The MBDA should also establish business centers at historically Black colleges and universities, tribal colleges and universities, and other minority-serving institutions—providing startup capital and technical support for students and community members interested in starting or expanding businesses. In line with other policy recommendations offered in a 2020 Center for American Progress report, the MBDA should “initiate an economic equity grant program that would fund municipal projects that foster wealth creation, opportunity, and minority business development in Black communities.”

Commit to opportunities for Black-owned businesses in infrastructure spending

As the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act’s federal dollars are delivered to state and local leaders, much of the work will be contracted out to small, medium-sized, and large businesses. This will be an important opportunity for leaders to follow through on their promises to lift the Black community by formalizing and building relationships with the Black businesses that create wealth for these communities. However, equity isn’t systematically built into the infrastructure bill; consequently, states will vary in their attempts to address past inequality and drive capital to Black-owned firms.

Empower more Black people as public fund managers

Municipal governments control large sums of capital in the form of pensions for public employee groups, developed and undeveloped real estate, public utilities, air rights, and other captive city-related funds and public assets. But globally, women and people of color manage less than 2% of capital.

To ensure public funds are managed by people who look like the public, we must be deliberate about funding a diverse set of fund managers. Diversity in asset management leads to diversity in investment; for example, Texas Woman’s University’s AssistHER grant program, which provided $10,000 grants to 100 women-owned businesses adversely impacted by the pandemic. Urban wealth funds are another innovative approach to public finance that involves mapping the commercial value of public assets and leveraging them to generate revenue that can be used to reinvest in community services, infrastructure improvements, and other worthwhile projects. Cities should demand that oversight of funds and assets maintains at least 30% representation from women and people of color.

Leverage philanthropy to support structural change

In the aftermath of 2020’s racial justice protests, large corporations pledged billions of dollars to the cause. Likewise, various charitable foundations—notably, corporate and grant-making foundations—provided billions to support Black businesses. The impact of these contributions remains to be seen as the pandemic rages on, taking a toll on low-wealth communities and the businesses in them. Future investments must be focused on altering the structures that prohibit maximum participation in markets.

Supporting Black businesses stuck in systems that extract Black wealth is akin to putting water in a bucket with a hole in it. Philanthropic funding certainly provided temporary relief, but we’re not going to “nonprofit” our way to better business outcomes. Philanthropic giving must encourage the kind of structural change at the federal, state, and local level that will allow the economy to work for everyone.