Virginia Tech helps Christiansburg Institute preserve Black history archives- Cardinal News

For 100 years, Christiansburg Institute battled white discrimination by serving as a model of Black education and culture tucked away in the mountains of Southwest Virginia. Today, the battlefield has transferred to a digital arena as the nonprofit that carries its name strives to preserve it for future generations.

A national effort to digitize archives and artifacts embodying African American history, which has long been ignored and inaccessible to the masses, began soon after the racial unrest of 2020. The digitization movement made its way to the institute, which once stood just down the hill from the current Christiansburg High School, after executive director Chris Sanchez and museum curator Jenny Nehrt successfully applied for a $250,000 grant from the Council on Library and Information Resources for “Digitizing Hidden Collections” in 2022.

“It’s basically immoral to underpreserve Black history in any society that claims to be democratic,” said Sanchez.

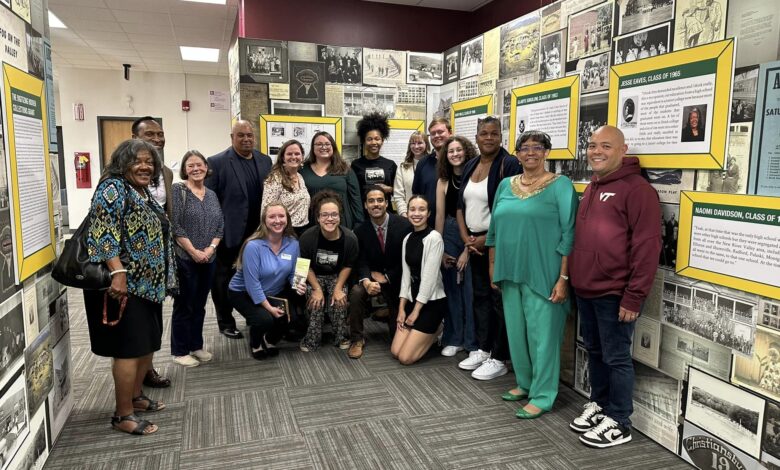

The nonprofit, in collaboration with University Libraries at Virginia Tech, recently finished scanning and uploading 870 photographs, 60 slides, 15 diplomas, 48,000 typed pages and 3,300 handwritten pages from the school’s heyday. These artifacts can now be accessed by anyone with an internet connection: https://hub.catalogit.app/8896. The collection will also be stored in the University Libraries’ digital space. An exhibit to promote the almost-completed work is open to the public until Dec. 17 on the second floor of the Newman Library.

“So it [the grant] was picture perfect for our collections because they have been hidden,” said Nehrt. “They’ve been gathered by alumni for decades. But because of institutional racism, that prevents organizations like ours, small grassroots but especially predominantly African American-operated, from accessing these resources. So there was a natural alignment.”

The grant money allowed them to fund several key aspects of the digitization operation: two new staff positions, a scanning technician and a metadata specialist, and $5,000 worth of equipment that the institute had previously been borrowing from the Montgomery Museum of Art and History. New scanning technician Demiah Smith painstakingly used these instruments — a flatbed to capture high-resolution images, an overhead scanner to avoid any impact on fragile papers, and a light box to provide a well-lit and clean background for 3D objects — to work her way through the 50,000 individual documents and artifacts.

Roughly 40,000 items have already been processed, and Nehrt estimated they are working through the last 20% of the archive. Recently hired metadata specialist Ashley Palazzo then carefully reviews every piece to analyze and record any information before uploading it to the C.I.’s digital archive.

“Going into the digital world with this grant has allowed us to reach a wider alumni and descendant community,” said Sanchez. “Also, reflect our broad national audience that connects with the story in a powerful way.”

Founded in 1867 by a Quaker group, Friends Freedmen’s Association, Christiansburg Industrial Institute served as a gathering of African American scholarship and culture for a hundred years. Thousands of Black students traveled from across Virginia and neighboring states to receive a high-quality education centered on the industrial arts that prepared them for the workforce. A significant portion of the staff were alumni of the Tuskegee or Hampton institutes, and Booker T. Washington visited to deliver a speech on the campus in 1910.

What started out in a single rented room expanded into a 185-acre campus boasting roughly 20 buildings with a range of academic, residential, recreational and medical purposes, including the only Black hospital in the area. The Montgomery County School Board shut down the historic institution when integration finally arrived in the late 1960s. Despite public outcry and legal agreements barring such action, the county held an auction in June of 1967 to sell off the 154 acres, divided into 16 plots, and eight buildings.

All that remains on 4 acres is a single academic building, a small smokehouse and the nonprofit Christiansburg Institute, with a mission of not only preserving the stories and relics of the school, but also educating others on its history — now made a little easier, said Nehrt.

“History is complicated, it’s messy and it’s created by humans. Because of that, biases have infiltrated how we talk and tell history since ever,” she explained. “It’s just so important that these records be made accessible because you can’t understand and recognize the things that have happened without being able to look at the proof of it that supplements the rich oral histories that already exist amongst the alumni. They know what they experienced, they lived through it. They told their family and friends their experiences, but the rest of us need to know too, we need to learn and hopefully be better.”

Adapting with the times, the historic school seeks to continue educating the next generation in the upcoming phase of its digitization project. The Christiansburg Institute plans to engage with local high school students by creating internship opportunities offering hands-on experience to those interested in public history, cultural preservation, digital humanities and museum education. Institute leaders also hope to construct a curriculum that will include the chronicle of C.I. in addition to other underrepresented local history, to assist and instruct teachers, as even many local residents are unfamiliar with the once-renowned Black school in their backyard, said Sanchez.

“Digitizing the history that in and of itself, is very worthy because that’s important,” said Sanchez. “Doing it digitally theoretically ensures it lives forever.”

* * *

The Christiansburg Institute is not an isolated case in Southwest Virginia. Saint Paul’s College in Lawrenceville was a private Black college founded in 1888 by James Russell Solomon, who was born into slavery. The school grew over the years alongside the surrounding Black community and, in 1941, the state granted it the authority of a four-year bachelor degree institution. Most notably, it developed the Single Parent Support System, an on-campus program that created an opportunity for single parents to be full-time students while receiving free child care, tutoring and counseling services, as well as courses in career planning and parenting.

In June 2012, the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools withdrew St. Paul’s accreditation for violations revolving around “financial resources, institutional effectiveness in support services, institutional effectiveness in academics and student services, lack of terminal degrees for too many faculty members, and a lack of financial stability,” according to an article in Inside Higher Ed. Several other historically Black colleges within SACS’s region were closed or placed on probation by the accrediting group, leading to some civil cases, all of which were unsuccessful for the colleges. Saint Paul’s officially shut its doors on June 30, 2013. Soon after, a local man, Bobby Connor, began to clear the buildings of any records and artifacts he could get his hands on to prevent its history from being erased. With the salvaged archives, a group of alumni organized the James Solomon Russell/Saint Paul’s College Museum and Archives, which opened in 2018 in an abandoned bank building.

According to a piece on NBC Washington, it was only a few years later when the museum found the national spotlight as representatives from the Smithsonian’s Robert F. Smith Center for the Digitization and Curation of African American History stopped by the museum along Main Street in Lawrenceville offering to help process, identify and digitize the collection.

“By bringing the Museum’s digitization services to diverse communities across the country and creating a unique online platform, the program supports the preservation and sharing of community history and culture,” according to the museum’s mission statement for their Community Curation Program.

Representatives of Saint Paul’s College Museum and Archives could not be reached for comment.

The work of the Christiansburg Institute and Saint Paul’s is only one piece of the puzzle portraying Black America over the years that activists and academics across the country are attempting to put together. In just the past few years, a range of organizations have made an effort to cement different aspects of African American life and culture into the historical canon.

In February 2022, Howard University was awarded a $2 million grant from the Jonathan Logan Family Foundation, which supports social justice initiatives, to digitize The Black Press Archives housed in the school’s Moorland-Spingarn Research Center. The archives contain more than 2,000 newspapers from the U.S., as well as some African and Caribbean countries, and have long been inaccessible to the public as the university lacked the resources to scan and process the collection.

The director of the Research Center said in an email to the Associated Press, “Once digitized, Howard’s Black Press Archive will be the largest, most diverse, and the world’s most accessible Black newspaper database.”

The Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture is conducting similar work. The museum has been relying on volunteers to transcribe and, more recently, digitize thousands of documents from a historic D.C. Black newspaper called the New Negro Opinion. The paper was formed by the New Negro Alliance in 1933 in response to white businesses in the city firing and replacing Black employees with all-white staffs. It documented the subsequent boycotts, picketing and Supreme Court case, New Negro Alliance v. Sanitary Grocery Co. The museum also focused on preserving and recording scientific books and an oral history telling the story of Black oyster workers in Chesapeake Bay.

The Smithsonian team has been salvaging historical newspapers as well as transcribing records from the Freedmen’s Bureau, a government organization formed to aid newly freed enslaved persons following the Civil War, according to Smithsonian Magazine. The 3.5 million pieces of previously inaccessible bureau paperwork are now available on a free, online portal recently created by Ancestry, the genealogy company. With these records now online, people can scour these caches of data to trace their family trees. This is especially beneficial to the descendants of enslaved people, as many have been unable to identify relatives due to inadequate records, including the exclusion of enslaved people from governmental censuses.

For some organizations, it is less a case of finding the manpower to transcribe old newspapers, but simply opening up boxes that have been collecting dust in the back corners of storage closets for decades.

In July 2020, The Harvard Gazette published a piece stating that the school’s Houghton Library was pausing all other digital projects to direct its attention on making virtually accessible thousands of materials on Black history that had simply been taking up space in their archives. A collection titled “Slavery, Abolition, Emancipation, and Freedom: Primary Sources from Houghton Library” contains 3,400 records ranging from letters written by Frederick Douglass and Sojourner Truth, bills of sale of enslaved people to pictures of African American infantry divisions in the Civil War.

Another hidden treasure trove collecting dust in a Chicago warehouse contained roughly five million magazines, audio files, business records as well as prints and negatives from the Johnson Publishing Company that has produced Black culture and entertainment magazines Ebony and Jet since 1945. Images of icons Ray Charles, Maya Angelou, Muhammad Ali and Aretha Franklin will eventually be digitized and released online following a seven-year joint project by the J. Paul Getty Trust and the National Museum of African American History and Culture, who share ownership of the archive since the Johnson Publishing Company went bankrupt in 2019.

Both of these campaigns recognize the importance of the task at hand. In an article on Getty’s website, Kara Olidge, the associate director for collections and discovery at the Getty Research Institute, acknowledged the “pivotal time” in the U.S. as many states are placing restrictions on the way in which schools talk about race and other aspects of history.

“We’ve always had these materials, but now we need to be proactive about access and accessibility,” said Houghton Library’s digital collections program manager Dorothy Berry in the Gazette article. “Making these materials accessible and showing we value them is a way of redressing a field that has historically not been welcoming to African Americans.”

The effort to promote and exhibit various aspects of underrepresented Black history, beauty, art, culture that have often been appropriated and whitewashed has inspired Instagram and X/Twitter pages with a devoted, worldwide following. Harvard-trained corporate lawyer and longtime cable television executive Julieanna Richardson has spent the last two decades sharing the oral histories of over 3,500 prominent Black individuals from politicians, athletes, musicians, literary artists, even Tuskegee Airmen through her nonprofit, The HistoryMakers.

“How else are you going to know what really has happened in the Black community if you don’t allow the community to speak for itself?” said Richardson during a “60 Minutes” interview with Bill Whitaker. “They’re America’s missing stories. And American history won’t be complete without them.”

Despite all that has been accomplished in recent years, there are still barriers blocking access to resources — like grants — for small grassroots organizations, said the Christiansburg Institute’s Sanchez. Grants may stipulate that applicants hold doctorate degrees or that a university handles the finances for the nonprofit. He and Nehrt managed to overcome these obstacles by demanding complete autonomy over the funds, which was allowed, and they hope to become a model for other groups in the future.

“It [The grant] was really centered in a new way of thinking about how higher ed and large universities are working with grassroots nonprofits like ours, which is dedicated to the preservation of Black history,” he said.